Tag Space & astronomy

UW-Madison’s Zweibel wins 2016 Maxwell Prize for Plasma Physics

University of Wisconsin–Madison astrophysicist Ellen Gould Zweibel has won the American Physical Society’s 2016 James Clerk Maxwell Prize for Plasma Physics.

Washburn Observatory open Monday for public viewing of Mercury crossing sun

Weather permitting, Washburn Observatory will be open to the public for safe viewing of the event.

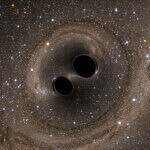

High Throughput Computing helps LIGO confirm Einstein’s last unproven theory

A software program pioneered at UW–Madison churned away in the background, helping analyze data from billions of particle collisions.

After long hiatus, Washburn Observatory public viewing to resume

The observatory had closed unexpectedly in April 2014 when a motor and gear box that operate a sliding door on the dome malfunctioned.

UW astronomer recognized for demystifying star system

Sebastian Heinz has been honored by the American Astronomical Society for his work to unravel the mystery of Circinus X-1, a bizarre binary star system in our galaxy that exploded some 2,500 years ago.

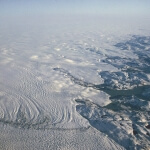

Clouds, like blankets, trap heat and are melting the Greenland Ice Sheet

A new study shows clouds are playing a larger role in heating the Greenland Ice Sheet than scientists previously believed, raising its temperature by 2 to 3 degrees compared to cloudless skies.

Study questions dates for cataclysms on early moon, Earth

Phenomenally durable crystals called zircons are used to date some of the earliest and most dramatic cataclysms of the solar system. One is the super-duty collision that ejected material from Earth to form the moon roughly 50 million years after Earth formed. Another is the late heavy bombardment, a wave of impacts that may have created hellish surface conditions on the young Earth, about 4 billion years ago.

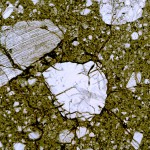

Ancient rocks record first evidence for photosynthesis that made oxygen

A new study shows that iron-bearing rocks that formed at the ocean floor 3.2 billion years ago carry unmistakable evidence of oxygen. The only logical source for that oxygen is the earliest known example of photosynthesis by living organisms, say University of Wisconsin–Madison geoscientists.

Recent sightings: Moon over Madison

Seen from the roof of Memorial Library, a supermoon rises in the nighttime sky behind the Wisconsin statue headdress atop the dome of the Wisconsin State Capitol building on Sept. 27, 2015.

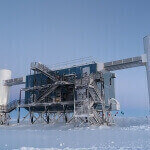

Balzan Prize goes to UW neutrino pioneer

Francis Halzen, the University of Wisconsin–Madison physicist and leader of the giant neutrino telescope known as IceCube, has been named winner of a 2015 Balzan Prize.

New data from Antarctic detector firms up cosmic neutrino sighting

Researchers using the IceCube Neutrino Observatory have sorted through the billions of subatomic particles that zip through its frozen cubic-kilometer-sized detector each year to gather powerful new evidence in support of 2013 observations confirming the existence of cosmic neutrinos.

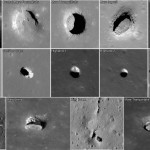

Novel Morgridge technology may illuminate mystery moon caves

It's widely believed that the moon features networks of caves created when violent lava flows tore under the surface from ancient volcanoes. Some craters may actually be "skylights" where cave ceilings have crumbled.

Neutron star’s echoes give astronomers a new measuring stick

In late 2013, when the neutron star at the heart of one of our galaxy’s oddest supernovae gave off a massive burst of X-rays, the resulting echoes — created when the X-rays bounced off clouds of dust in interstellar space — yielded a surprising new measuring stick for astronomers.

Dark energy to be topic of Space Place event

"To Infinity and Beyond: The Accelerating Universe," a live broadcast from the World Science Festival about dark energy, an antigravitational force that confounds the conventional laws of physics, will be hosted on the evening of May 28 by UW–Madison's Space Place.

Wisconsin contributions helped Hubble Space Telescope soar

It was “the flea on the tail of the dog.” Roughly 30 years ago, that was how University of Wisconsin–Madison astronomy Professor Robert C. Bless described the High Speed Photometer (HSP), a detector then under development at UW–Madison for the soon-to-be-launched Hubble Space Telescope.

Hubble Space Telescope to star at April 14 Space Place event

Twenty-five years of spectacular imagery and groundbreaking astronomy from the Hubble Space Telescope will be the subject of a Tuesday, April 14 public presentation at UW–Madison’s Space Place.