UW research in 2022: From restored prairie to scorpion venom to the sewer

Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a powerful reminder of the ways in which science affects our daily lives. But with the success of effective vaccines (including boosters, adapted to current strains) and a high level of population immunity, this year saw a shift in the science stories that grabbed our attention.

The research communications team at the University of Wisconsin–Madison ‘oohed’ and ‘ahhed’ along with the rest of the world as the first photos emerged of the black hole at the center of the Milky Way and as the Webb Telescope unfurled its massive sun-shield and shared back stunning images of galaxies billions of light-years away.

But the team, which this year lost one member (best wishes in your new role, Eric Hamilton) but added two more (welcome, Elise Mahon and Will Cushman), also gleefully uncovered our own science stories on campus that wowed and inspired us. We were simply too excited by the incredible, innovative and meaningful work carried out by UW faculty, staff and students daily not to help but share it.

Here — from Will and Elise (that’s pronounced “Uh-LIS-uh”), Chris Barncard and Kelly Tyrrell, who’s both a science writer and director of media relations and strategic communications (and a bonus pick from the university’s new internal communications editor, Caitlin Henning) — are some of the stories from around campus that stood out most in 2022.

Steve and Susan Carpenter are pictured on their restored 100-acre prairie in the Driftless Area on Aug. 25, 2022. Photo: Althea Dotzour

On a late summer evening, in the cast of golden evening light, University Communications photographer Althea Dotzour, science writer Elise Mahon and Kelly Tyrrell loaded into a van and wandered to the Driftless to visit ecologist Steve Carpenter and UW Arboretum native garden curator Susan Carpenter on their slice of conservation land. There was no hard data to explain or manuscript in process. Instead, it was an opportunity to celebrate (in photos and video!) that science can simply be just another way of appreciating the world — and the people — around you.

Aaron LeBeau feeds nurse sharks pieces of squid in his research lab on Dec. 15, 2021. LeBeau has discovered antibodies from sharks that can neutralize COVID-19 and related coronaviruses. Photo: Bryce Richter

Coronavirus, cancer, meet sharks

If swimming with sharks sounds dangerous to you, you’re not alone — even the virus that causes COVID-19 is haunted by the “Jaws” theme. Just after we picked our favorite science stories of 2021, we learned about a group of nurse sharks making small blood donations that could take the bite out of future pandemic viruses. Sharks (and, weirdly, llamas) have tiny, antibody-like proteins called VNARs in their blood that have proven incredibly efficient at binding with important parts of coronaviruses. Aaron LeBeau, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, says the VNARs are cheaper and easier to manufacture than human antibodies and may also have a future diagnosing and treating cancer.

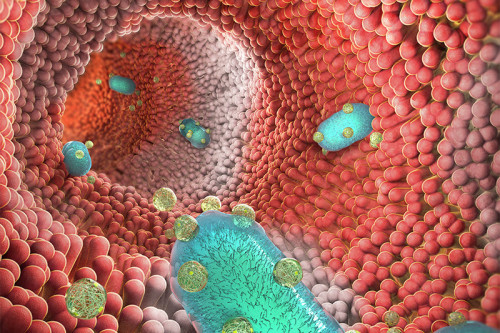

Probiotic bacteria (teal) coated in a layer of biomaterial as they travel through a human intestine. Quanyin Hu

Bacteria with backpacks to help your gut

Who hasn’t thought of backpack-toting bacteria as elite firefighters wading into the danger zone to fight out-of-control fires? If you haven’t, that might be because you haven’t yet read this story, about a new strategy aimed at treating inflammatory bowel disease. The idea, led by biomedical engineer and UW School of Pharmacy Professor Quanyin Hu, is to equip gut-friendly bacteria with nanoparticle “backpacks” filled with a therapy to track down the molecules responsible for causing damaging inflammation in the intestines. While human studies are still to be done, Hu is excited about the potential to more holistically treat disease.

A female Tityus costatus scorpion from Brazil makes toxins that can kill humans, but components of deadly scorpion venom are also being studied for antimicrobial and anti-tumor properties. Photo by Carlos Santibáñez-López

Venoms to kill, venoms to heal

Somewhere around 70 million years ago, during the dawn of the age of mammals, new animals like shrews — and later bats, rodents, mongooses and badgers — developed a taste for scorpions, which by then had already been around for about 350 million years. But the scorpions had a few tricks up their curved tails — they began to evolve new venoms that worked against their new predators. Today, researchers like Integrative Biology Professor Prashant Sharma and his former postdoc, Carlos Santibáñez-López, are studying the potential of these venoms to serve any number of medical purposes, including as “tumor paint.”

Members of the dive team lift a makeshift raft holding the canoe onshore. Photo: Bryce Richter

A vessel, says UW–Madison alum, Bear Clan member and public relations officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation Casey Brown, is imbued with the spirits of its creators. And so it is that last summer, alum and Wisconsin Historical Society maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen made a shocking discovery 27 feet below the surface of Lake Mendota: an intact, 1,200-year-old canoe made of caašgegura (white oak), built by the ancestors of the Ho-Chunk. Researchers at UW–Madison are contributing to understanding the canoe and tracing its story, and fragments of two other vessels have since been found near the site of the first. The People of the Mother Tongue had the first word, and they will certainly have the last, Megan Provost writes for On Wisconsin.

Summer Sherman is collecting lots of foam. Thanks to the help of citizens with an interest in pollutant-free drinking water, the UW–Madison postdoc in the lab of engineering professor Christy Remucal is studying the foam that collects in waterways for the presence of harmful contaminants known as PFAS. This video story traces her work from “foam call” to lab.

Red colobus monkeys in Kibale National Park, Uganda. The species are natural hosts of arteriviruses related to SHFV. Tony Goldberg

‘A pretty controversial prediction’

For as long as humans and other animals have had contact with one another, they’ve also shared disease. Tony Goldberg, a professor at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine, is always on the hunt for the next virus that could spill over and cause a new pandemic. This year, he and collaborators across the country sounded the alarm about a little-known virus detected in wild African primates, which has never been found in humans. The story dissects the controversy underlying this kind of detective work, uncovers details about the scientific process and highlights the personalities that drive it.

Co-opting bacteria in a fight against addiction

The gut is a weird place with a lot more say in your life than you would expect. In fact, bacteria that live in the intestines may make the brains of cocaine users more susceptible to the drug — and may have shown UW–Madison researchers studying mice a surprising way to prevent cocaine addiction.

Wearing face shields, Physical Plant plumbers Jay Maier, left, and Adam Kundert hoist a compositing wastewater sampler from a sewer opening near the lakeshore residence halls at the University of Wisconsin–Madison on Sept. 1, 2020. Photo: Jeff Miller

Poop can tell you a lot about yourself and those around you. Or at least, that’s what’s driving UW–Madison pathology and laboratory medicine professor David O’Connor’s latest efforts to test what’s lurking in human waste. The goal: Identify “cryptic lineages” of the virus that causes COVID-19. They could be responsible for the next variants of concern. Meanwhile, Shelby O’Connor, also a UW professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, is turning to what can be measured in the air to help people mitigate their risk of getting sick with a number of respiratory illnesses. Their work is practical, actionable and acknowledges the realities of COVID fatigue.

In a study of anonymized data on 1.6 million menstrual cycles from 267,000 adults using an app, UW–Madison sociology professor Jenna Nobles found that roughly one in five people experience irregular menstrual cycles that could mask pregnancy until it’s too late to access legal abortion. The first sign of pregnancy for many people is a missed period, but by the time some know to take a pregnancy test, they may have already missed the window. This degree of variability, Nobles says, is not widely appreciated and the study reveals the potential impact of policies that don’t take important aspects of physiology into account.

Brad Herrick, the Ecologist and Research Project Manager at the UW–Madison Arboretum, pulls an invasive jumping worm out of a Madison backyard as part of a survey aimed at monitoring the species’ population and geographic spread across Dane County. Elise Mahon

Getting the jump on jumping worms

This summer, gardeners, Friends of the Arboretum, Boy Scouts and nature lovers united on a quest to uncover and understand the spread of the invasive jumping worm, wreaking havoc on soil quality across the U.S. and in the Madison Metro Area. “We’re still at the forefront of this invasion, so it’s a really cool opportunity to track [it] from the inception and maybe keep this isolated or contained,” says ecologist and UW Arboretum research project manager Bradley Herrick.