Teaching Indigenous land dispossession in Wisconsin and beyond

In the 1860s, the University of Wisconsin was granted more than 230,000 acres of land to make pursuing an education in agriculture, military tactics, mechanical and classical arts attainable for the state’s working class.

This was the mission of land-grant universities, as dictated by the 1862 Morrill Act. But where did the land granted to the university come from?

While land-grant universities produce important scholarship and research that gives back to their states, they can do so because of the wealth and real estate gained from the dispossession of Indigenous lands.

In total, 1,337,895 acres of land across Wisconsin were taken through treaties with the Menominee, Ojibwe, Dakota, and Ho-Chunk and redistributed through the Morrill Act to benefit 30 land-grant universities around the country. Yet many students coming to UW–Madison (and other land grant universities across the country) don’t know that part of the story. Many don’t know the Indigenous history of the place now called Wisconsin.

Thanks to new funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, an interdisciplinary group of UW–Madison faculty, staff and graduate students will be able to help teach this history by creating educational modules about the expropriation of Indigenous lands.

Kasey Keeler

“There is a huge disconnect if you don’t know American Indian history, you don’t know the tribal nations of the state and you don’t know how treaties worked,” says Kasey Keeler, an assistant professor of Civil Society and Community Studies and American Indian Studies. “But when you can kind of connect the dots, I think it’s really, really powerful. And I think this project can do that.”

Keeler will be working alongside four other professors at UW–Madison, most of whom are junior faculty, to lead a larger, cross-departmental team creating and integrating these educational modules into courses across campus.

The modules will define key terms and concepts behind land-grant universities and dispossession of Indigenous land, explore the historical context of legislation and policy happening at the time land-grants were being designated, and look at how these lands were transferred from Indigenous groups to individuals and institutions through time.

The team intends to make the information accessible to local Native and non-Native communities — not just the UW–Madison campus — and it also hopes the curriculum will inspire other land-grant universities to create similar curricula for their own campuses.

The group came together after realizing many faculty on campus were starting to integrate this knowledge into the courses they teach. Many had students read a pivotal article in High Country News called Land Grab Universities, and study related maps and materials gathered by investigative journalists Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone, alongside cartographer Margaret Pearce. Several also had students visit spaces on campus, such as the Ho-Chunk burial mounds on Observatory Hill, to think about different spaces’ histories.

“I had my class go outside to these mounds and just kind of sit and take that in,” Keeler says. “I think that’s when they start getting it, to see these physical places on the landscape that mark Ho-Chunk history and to think about how all of that was just taken away to build a university.”

When students in their classes learn about this history of land dispossession, they are usually shocked, outraged, saddened.

Jen Rose Smith

“This is very common in Native studies classes. The refrain of, ‘I did not know this, why was I never taught this?’” says Jen Rose Smith, an assistant professor of geography and American Indian Studies also working on the project.

She says many of her students are also often motivated to learn more and ask what they can do now. Smith is excited that the funds from the NEH grant will help the team provide stipends to motivated students who want to assist in building the curriculum.

The grant will also help them compensate Native community members who volunteer their time and share their perspectives with the team as they create these modules. While both Smith and Keeler are Native — dAXunhyuu (Eyak) and Tuolumne Me-Wuk & Citizen Potawatomi respectively — no one in the group of researchers is a member of a Wisconsin First Nation. So far, they’ve had meetings with members of the Ho-Chunk, Oneida Nation, and Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians.

“We wanted to get input from the Native community, first and foremost, to see how they wanted their histories and histories of dispossession to be narrated, if they did at all,” says Smith. “Being a Native person who’s working and living in a place that is not my homelands, I feel like this is part of my responsibility of what it means to be a Native faculty member at a land-grant university.”

Caroline Gottschalk Druschke

In addition to Keeler and Smith, the team will include Ruth Goldstein, a professor in the women and gender studies department, Joe Mason, a professor of geography, and Caroline Gottschalk Druschke, a professor in the English department and principal investigator of the grant.

Currently, the team plans to integrate the modules into 22 identified undergraduate and graduate courses, which have the capacity to reach 3,000 students each year across eight departments and programs. Professors who want to incorporate the curriculum into their courses will be able to adapt the information to fit their own needs and class material as well.

Most of the work now is focused on determining the best way to present information, whether through building modules on Canvas or making materials available through PowerPoint and other tools.

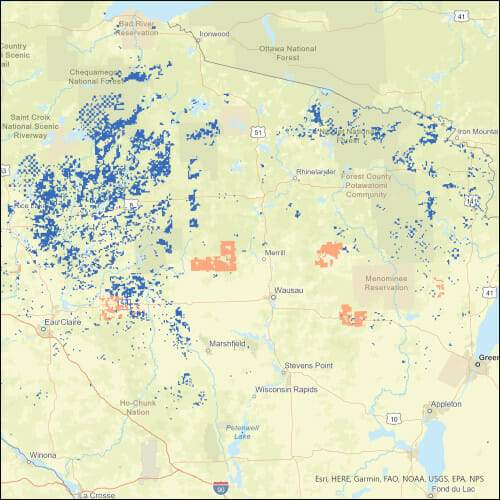

Using data from the Land Grab Universities article, Joe Mason, a professor of Geography at UW—Madison, is working to create maps for the new education modules. This portion of a map of Northern Wisconsin shows parcels of land that the University of Wisconsin was granted via the Morrill Act in orange, and parcels that other universities were granted in blue.

Since the members of the team are from a number of different departments, they will have more ways of delivering the curriculum to a wide range of the student body. Gottschalk Druschke said that while their diverse research backgrounds inform how they approach building the curriculum, the knowledge they gain while doing this work also affects their own research. And sometimes also their personal lives.

“Education is important but it’s not the only thing we should do,” says Gottschalk Druschke. “So, I do hope that this gets folks thinking, especially about questions like, ‘How do you want to live your life in light of this information?’ I think it’s something that settlers like me can be held accountable to.”

Land-grant universities received land from the federal government that they subsequently profited from to fund their campuses, in many cases distinct from the land their campuses are built on. The university campus in Madison sits on ancestral Ho-Chunk land. The Morrill Act of 1862 granted the University of Wisconsin 235,530 acres of land taken through the 1837 Treaty with the Chippewa (Ojibwe), the 1842 Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi and Lake Superior (Ojibwe), and 1831, 1836, and 1848 Treaties with the Menomini (Menominee).

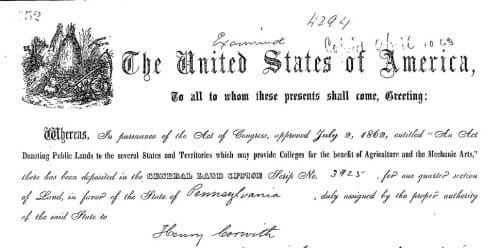

A General Land Office patent for a parcel in Taylor County, Wisconsin. Henry Corwith bought the parcel using scrip purchased from Pennsylvania to benefit Penn State. Corwith was the “wealthiest man in northern Illinois” outside Chicago, thanks mostly to land speculation.