Nationwide maps of bird species can help protect biodiversity

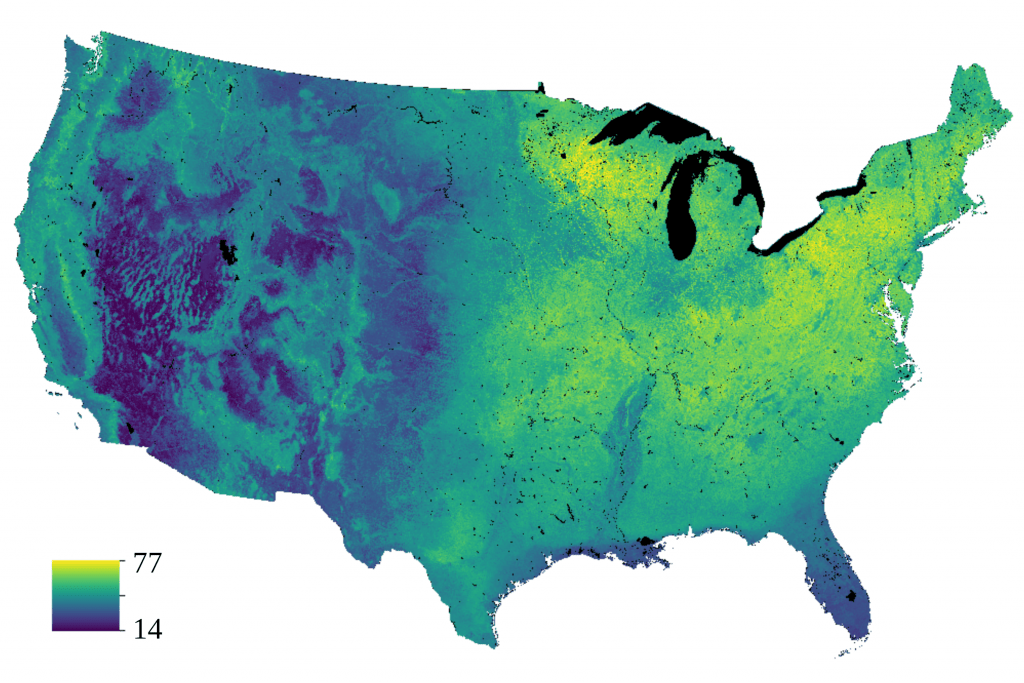

Researchers mapped the number of bird species found across the contiguous U.S. Blue areas host fewer bird species than green or yellow areas do. Images by Kathleen Carroll and Anna Pidgeon

New, highly detailed and rigorous maps of bird biodiversity could help protect rare or threatened species.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison developed the maps at a fine-enough resolution to help conservation managers focus their efforts where they are most likely to help birds — in individual counties or forests, rather than across whole states or regions.

The maps span the contiguous U.S. and predict the diversity of birds that live in a given area, related by traits such as nesting on the ground or being endangered. Those predictions are based on both detailed observations of birds and environmental factors that affect bird ranges, such as the degree of forest cover or temperature in an area.

Anna Pidgeon

“With these maps, managers have a tool they didn’t have before that allows them to get both a broad perspective as well as information at the level of detail that’s necessary for their action plans,” says Anna Pidgeon, a professor of forest and wildlife ecology at UW–Madison who helped lead the development of the maps.

Pidgeon worked with UW–Madison professor Volker Radeloff, postdoctoral researcher and lead author Kathleen Carroll and others to publish the research and the final maps April 11 in the journal Ecological Applications. The maps are available for public download from the open-access website Dryad.

The research was designed to address two outstanding problems in conservation.

“Across the world we’re seeing huge species losses. In North America, 3 billion birds have been lost since 1970. This is across virtually all habitat types,” says Carroll. “And we’re seeing a disconnect between what scientists produce for conservation and how that translates to boots-on-the-ground management.”

Many resources previously available to conservation managers, such as species range maps, are both at too broad of a scale to be useful and not rigorously tested for accuracy.

Kathleen Carroll

To overcome those challenges, Carroll and her team wanted to develop data-driven maps of existing bird biodiversity. They produced the maps by extrapolating observations of birds from scientific surveys to mile-by-mile predictions of where different species really live. Those predictions were based on factors including rainfall, the degree of forest cover and the extent of human influence on the environment, such as the presence of cities or farms.

To improve the predictive power of their maps, the scientists clustered individual species by behavior, habitat, diet, or conservation status — such as fruit eaters or forest dwellers. These groups are called guilds. Many conservation decisions happen at the guild level, rather than at the level of species. Guilds can also make up for limited information on the most endangered species.

The final maps cover 19 different guilds at resolutions of 0.5, 2.5 and 5 kilometers. While the finest-grained maps were not as accurate, the 2.5-kilometer-resolution maps provided a good balance of accuracy and usefulness for realistic conservation needs, say the scientists. At the 5-kilometer resolution, the maps provide the greatest accuracy and are useful to conservationists operating across large areas.

“We see this being really applicable for things like forest management action plans for the U.S. Forest Service,” says Carroll. “They can pull up these maps for a group of interest, and they can get a very clear indication of what areas where they might want to limit human use.”

The maps may also help private land conservancies decide where to prioritize limited resources to maximize biodiversity protections.

Carroll is now working to extend the analysis down to individual species, rather than guilds made up of multiple species. The increased level of detail could help specialist conservation managers improve their work, especially those aiming to protect a single species.

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Geological Survey Landsat Science Team (grants G17PS00256) and the NASA Biodiversity and Ecological Forecasting Program (grant 20-BIODIV20-00460.