How disabling one gene protects mice against Type 1 diabetes

UW–Madison researchers have discovered a mechanism that could one day help people at risk of developing the metabolic disease.

Scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have uncovered a possible way to protect key cells in the pancreas that are targeted during the development of Type 1 diabetes.

The researchers found that deleting a single stress-response gene in insulin-producing cells protects mice that are genetically predisposed to Type 1 diabetes from developing the disease. The findings suggest a new path to reduce stress inside those cells and alter how the immune system responds, potentially opening new avenues for early intervention or prevention.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when immune cells destroy pancreatic beta cells, leaving the body unable to produce enough insulin to regulate blood sugar. To date, most treatments have focused on suppressing immune activity.

“Historically, because it’s an autoimmune disease, scientists and clinicians have focused on preventing the immune attack,” says Feyza Engin, a professor in the UW–Madison Department of Biomolecular Chemistry who led the research, which was recently published in Nature Communications. “We looked at it from another angle and asked: Why are beta cells specifically targeted?”

The new research centers on a protein called XBP1. It’s part of a cellular stress response system that helps cells cope with inflammation, environmental toxins and the buildup of misfolded proteins. Earlier work from Engin’s lab showed that deleting a related stress sensor, Ire1α, in beta cells also prevented diabetes in mice. The new study builds on that foundation.

Using a mouse model that spontaneously develops Type 1 diabetes, Engin and her colleagues deleted the Xbp1 gene specifically in beta cells before immune assault. Although the mice initially showed elevated blood glucose, they later returned to normal glucose levels and remained healthy for as long as a year.

“What was really interesting is that early on they show hyperglycemia, but then they recover from it,” Engin says. “They actually go from diabetes back to normal blood glucose levels.”

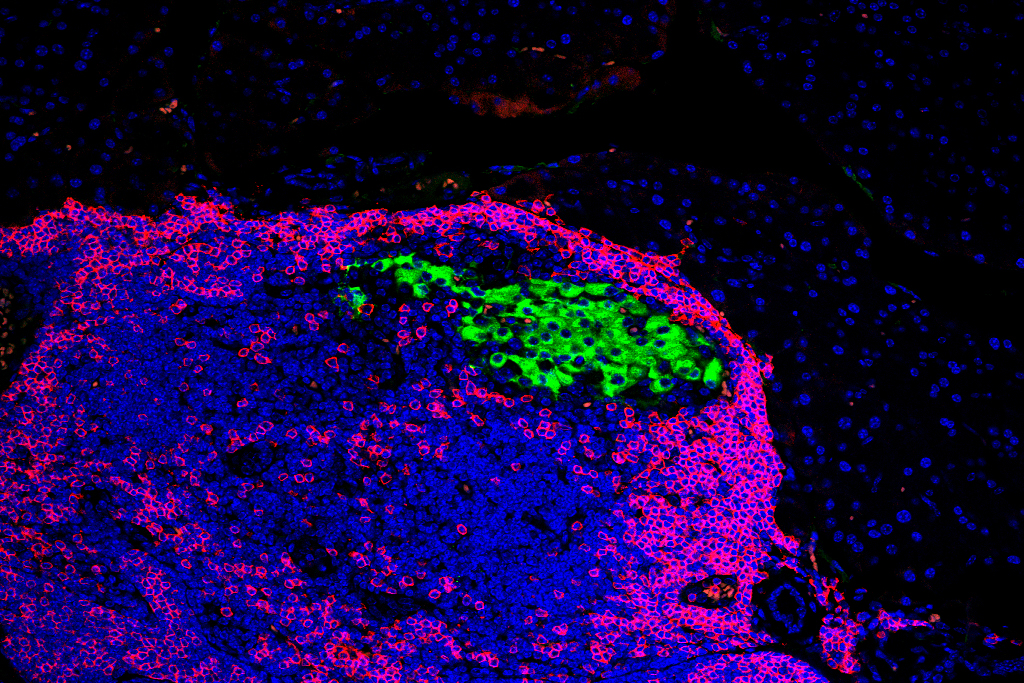

An analysis revealed that beta cells lacking the Xbp1 gene temporarily lost features that mark them as mature insulin-producing cells. During this phase, immune cells were less likely to recognize and attack them. Over time, the beta cells regained their identity, inflammation decreased and insulin production recovered.

“They’re losing their beta cell identity and look nothing like a typical beta cell,” Engin says. “That’s why immune cells don’t recognize them.”

Importantly, the protective effect occurred without any changes to another stress-related process involving Ire1α, helping to clarify how different components of cells’ stress response influence the disease.

To better understand those differences, the team compared beta cells lacking Xbp1 with those missing Ire1α under identical environmental conditions — an important part of Type 1 diabetes research, where environmental conditions like housing and diet can affect disease rates in mice. Using single-cell sequencing from these mouse models and gene regulatory network analysis performed by UW–Madison collaborator Sushmita Roy’s lab, the team identified both shared stress pathways and ones involving only Xbp1.

“We found unique gene regulatory networks specific to Xbp1 that was never discovered before,” Roy says.

The findings add to evidence that beta cells play an active role in Type 1 diabetes rather than serving as passive targets.

“Our findings further support that beta cells are actually not victims,” Engin says. “They actively participate in their own destruction.”

While the study was conducted in mice, Engin says the work is designed with human disease in mind. People at high risk for Type 1 diabetes can often be identified years before symptoms appear through blood tests.

“If you identify these people who will develop diabetes at that stage, can we interfere?” she said. “Can we inhibit XBP1 and prevent or delay their diabetes?”

The lab is now actively pursuing those questions in further studies, Engin says, both in mice and in lab-grown human pancreatic cells.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32 GM007215; DK130919; DK128136; 3-SRA-2023-1315-S-B; 3-SRA-2025-1654-S-B; and R01 GM144708), Greater Milwaukee Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center.

Research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison drives innovation, saves lives, creates jobs, supports small businesses, and fuels the industries that keep America competitive and secure. It makes the U.S.—and Wisconsin—stronger. Federal funding for research is a high-return investment that’s worth fighting for.

Learn more about the impact of UW–Madison’s federally funded research and how you can help.