UW’s influential sleep researchers get ideas during walks in woods

Chiara Cirelli (left) and Giulio Tononi, enjoy daily walks on their rural property, where they discuss their latest sleep research. John Maniaci

Every morning, sleep researchers Chiara Cirelli and Giulio Tononi have a routine that is as Italian as they are, and as Wisconsin as their log home in southwestern Dane County.

First is the espresso, without sugar, but often accompanied by answering e-mails. The two — who both hold M.D.s and Ph.D.s — roast and grind their coffee beans and brew them in an espresso maker that would be the envy of any professional barista.

Then, no matter the weather, it’s time for their hour-long hike on the trails of their heavily wooded property. It’s where they do some of their most important science — discussing ideas and plans for their next rounds of experiments at the Wisconsin Institute for Sleep and Consciousness (WISC) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

In the summertime, their walks take them through oak groves full of blooming wild roses, where they often surprise turkey and deer. They pass tangled roots of oak trees, uprooted in past storms, have been painted bright blue by Cirelli to symbolize the neural synapses so important in their “synaptic homeostasis hypothesis,” or “SHY,” which posits that sleep is the price we pay for brain plasticity. They also pass a painted symbol of the Greek letter Phi, which symbolizes Tononi’s theory of consciousness, described in his 2012 book, “Phi: A Voyage from the Brain to the Soul.”

Breakthroughs in sleep research

Cirelli and Tononi’s walking discussions have led to many breakthroughs in sleep research, including studies that received international attention in 2017: Cirelli’s paper in Science that provided visual proof of SHY and Tononi’s article in Nature Neuroscience that turned conventional knowledge about dreams on its head. The study showed that the “hot zone” for dreams and consciousness is located in the back of the brain and that researchers can predict the content of dreams based on which specific brain areas show heightened activity.

The world’s biggest sleep conference, Sleep 2017 in Boston, featured a debate between Cirelli and another scientist on SHY. In late 2017, Cirelli and Tononi will receive Harvard University’s Farrell Prize in Sleep Medicine for their career-long contributions to sleep research, and they will teach an advanced course on sleep at the Neuroscience School of Advanced Studies in Siena, Italy.

Tononi recently received the Zülch Prize from the Max Planck Society in Germany for his work on sleep and consciousness. And at the invitation of Google’s artificial-intelligence guru, Tononi will head to Cambridge University to discuss whether machines can be conscious (his theory says “no”).

At home in Wisconsin

This duo regularly attracts offers to move their lab to other universities around the world, but their morning walk is among the many reasons they stay in Wisconsin.

“It would be very difficult for us to beat this quality of life,” says Cirelli. “Together with working in a supportive environment that values research, it is key for us to have lots of space and be left alone. It’s hard to have someplace like this, anywhere in the world, so close to nature and yet so close to the lab.”

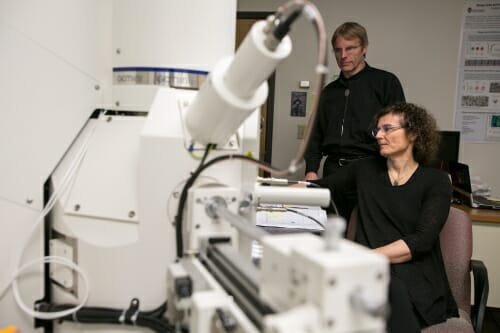

Chiara Cirelli, left, and Giulio Tononi have both done groundbreaking research at the Wisconsin Institute for Sleep and Consciousness at UW—Madison. John Maniaci

“Drs. Cirelli and Tononi are remarkably creative and innovative scientists,” says Dr. Robert Golden, dean of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH). “The stunning depth and breadth of their research runs the entire spectrum from basic cellular and animal model studies to translational and clinical investigations which have direct impact on human health and disease.”

Both professors in the SMPH Department of Psychiatry, Tononi and Cirelli met in 1984 at the University of Pisa Medical School in Italy. Tononi was a psychiatry resident, and Cirelli worked as a medical student in his sleep lab. She kept the research going when he left for New York, and then for San Diego to do theoretical work at The Neuroscience Institute. Later, she moved her career to San Diego to keep working with Tononi on sleep research.

At meetings, Cirelli met with Ruth Benca, then a UW–Madison SMPH professor of psychiatry who is now the chair of psychiatry and behavioral health at the University of California, Irvine. Benca invited Cirelli to check out Madison.

“Even though we were not really on the job market, Giulio and I said, ‘Yes,’ ’’ Cirelli recalls of their 2001 move to UW–Madison.

Research at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health

Cirelli and Tononi now direct a joint lab at the HealthEmotions Research Institute, part of the SMPH Department of Psychiatry, led by Ned Kalin, the Hedberg Professor and Chair of Psychiatry. Their lab has more than 20 researchers and may be one of UW–Madison’s most international groups, currently with faculty and staff from Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Poland and Switzerland. If you follow the aroma of freshly brewed espresso, you’ll find this group above the Wisconsin Sleep Clinic on the west side of Madison.

UW-Madison’s research on sleep runs the gamut, including Cirelli’s basic research on the nature of sleep in animals as small as rats, mice and fruit flies. (Yes, fruit flies sleep, as her lab showed by using tiny probes to sample the flies’ sleep/wake activity.)

Tononi’s work on consciousness and its practical, theoretical and ethical implications have been supported, among others, by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and — in collaboration with Larissa Albantakis, a UW–Madison scientist — the Templeton World Charity Foundation.

WISC researchers collaborate with clinicians ranging from neurologists and psychiatrists to meditation researchers throughout UW–Madison, and beyond. Joint work with Robert Pearce and Rob Sanders, professor and assistant professor, respectively, from the Department of Anesthesiology, is illuminating the mechanisms through which the brain becomes disconnected from the external world and falls into unconsciousness during sleep and anesthesia.

Another 2017 paper, funded in part by Lily’s Fund and led by Melanie Boly, clinical neurophysiology fellow, and Rama Maganti, a neurology professor and director of the UW Health Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, in collaboration with Tononi, looked at how epilepsy affects sleep. It showed that small spikes of electrical activity during sleep all night disrupt its restorative function, possibly causing daytime cognitive difficulties that can afflict people with epilepsy.

A few years ago, the laboratory studied the sleep of people with schizophrenia and found a dysfunctional pattern of brain waves during sleep that has been confirmed by several labs. Other studies have shown dysfunction in the sleep of people who eventually develop Alzheimer’s disease.

“Sleep truly is a window on the brain,’’ says Tononi, who holds the David P. White Chair in Sleep Medicine at UW–Madison and is the director of the WISC. “It’s a time when the brain is left to its own devices, so you can see how it is working without the confines of the environment or whether someone is paying attention. At night, we like to say, everyone is the same: the king and the beggar, the wise and the fool.”

Sleep and brain recovery

SHY holds that sleep is essential for brain recovery in all animals, making it a unique way to understand disease and health. It states that sleep cleans out unnecessary traces from the previous day by shrinking brain synapses and clearing space so more can be learned.

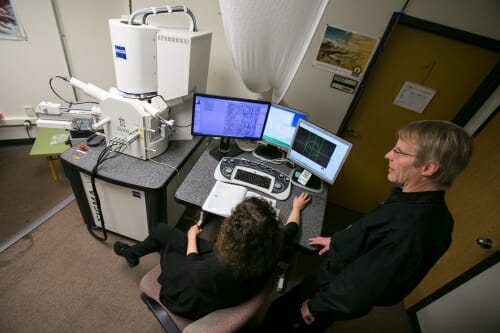

Chiara Cirelli and Giulio Tononi in the lab at the Wisconsin Institute for Sleep and Consciousness. John Maniaci

“This is why sleep is so essential,” Cirelli says. “Synapses are the foundation of brain function, the way cells communicate with each other. Just a few hours of sleep shrinks them 18 percent on average. The implication is that sleep is fundamental for the brain to function, learn and remember—and to forget, which is just as important. It’s strong evidence we need to be very protective of our sleep.”

Studies show that a single missed night of sleep makes it harder for people to learn, cuts their attention span and makes it harder to speak fluently, assess risks and appreciate a good joke. But Tononi believes sleep loss over the long haul is even a bigger threat to health and well-being.

“It’s a lot like food; it’s not so much what you eat on any one day, but what you eat over the long run that’s important,’’ Tononi says. “It’s difficult to test, but based on SHY, we believe sleep is essential for integrating new learning with old knowledge.”

He believes a limitation in machine learning is the lack of sleep-like processes to integrate knowledge, forcing machines to start from scratch to learn new things.

On Cirelli’s side of the lab, work continues using the electron microscope to measure synapse strength in new areas of the brain and the developing brain. She’s particularly interested in the effects of sleep deprivation in young animals, noting that it’s possible sleep has a different role while the brain is growing. She’s also eager to find out how sleep changes the brain after an animal has experienced a specific learning task.

Both Cirelli and Tononi are interested in seeing whether it’s possible to enhance the restorative effects of sleep. For now, SHY is central to the debate of why we need sleep. Cirelli says, “The debate is not settled, but this is a good time for sleep research because we are getting close to an answer, and we have powerful new tools to use.”

And it’s also a good time for sleep research because — after long days at the lab — they can return to their hilltop and walk among the oaks, as they talk science, integrate their new knowledge and restore themselves to learn more about sleep.