UW–Madison project combines art, policy and science to create plant-based plastics and benefit marginalized communities

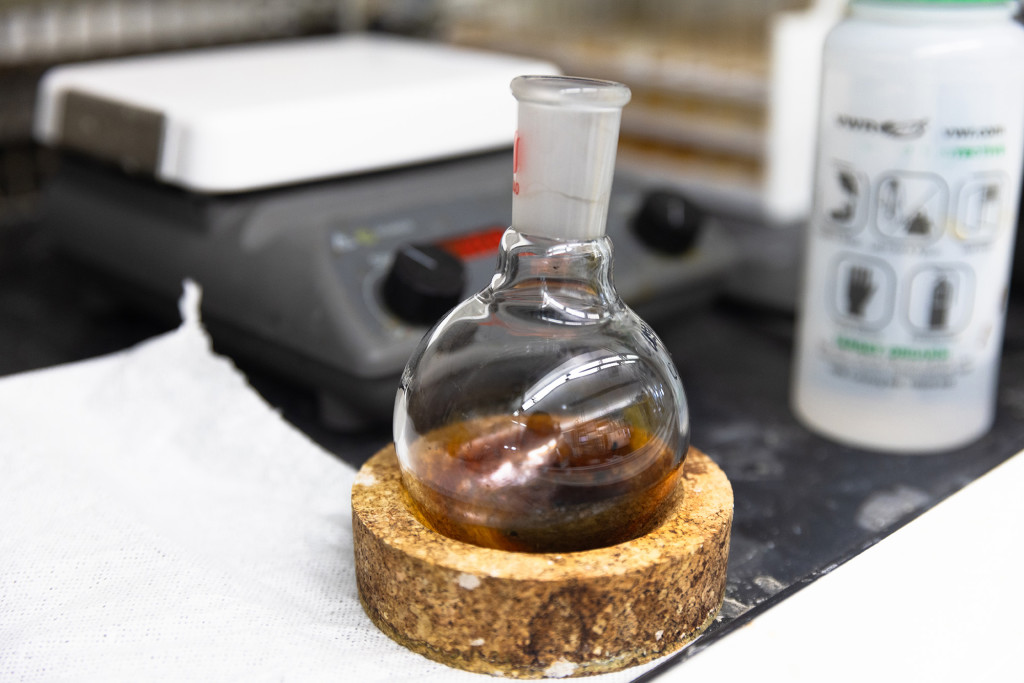

Shown here in a glass beaker, lignin — a complex substance that makes plants strong — could provide an alternative to petroleum-derived chemicals like benzene, toluene and xylenes that serve as building blocks for plastics, biofuels and solvents as well as drugs and food additives. Photo by: CHELSEA MAMMOT

A team led by University of Wisconsin–Madison scholars has a plan to turn paper mill waste into plant-based plastics, slashing greenhouse gas emissions and other pollution and creating economic opportunities in ways that benefit marginalized communities.

The U.S. Department of Energy has awarded $4 million to fund a collaboration between Wisconsin Energy Institute researchers, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and industry partners. The work will leverage contributions from experts in bacteriology, chemistry, engineering, public policy and the arts.

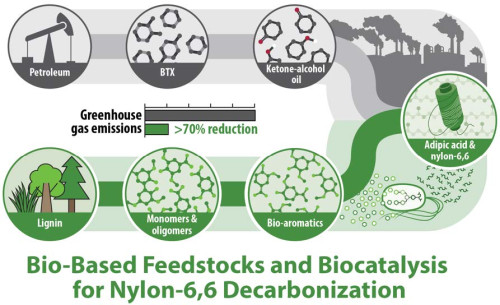

The project aims to deliver 10 kilograms of plant-derived chemicals used to make molded plastic parts and textiles. By using lignin from poplar trees instead of petroleum, the process could reduce associated greenhouse gas emissions by more than 70%.

The goal is to turn a fibrous plant material called lignin into nylon — used to make textiles, carpets and molded plastic — for roughly the same cost as the petrochemical version but with only a fraction of the pollution that causes climate change.

If successful, the project will demonstrate the commercial viability of a lab-tested process that could be key to developing sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels and petrochemicals, says Shannon Stahl, a UW–Madison professor of chemistry who is leading the project.

Shannon Stahl Photo By: JAMES RUNDE

“If you’re really going to replace petroleum with bio-based feedstocks, everything from plants has to be turned into value,” Stahl says. “The approach must be like petrochemicals, where everything from crude oil is turned into something of value. The goal is to adapt the petrochemical model to a biochemical context.”

But the project aims to go far beyond the engineering challenges by incorporating a plan to collaborate with communities disproportionately affected by pollution, climate change and economic hardship.

Morgan Edwards, professor of public policy and leader of the Climate Action Lab, will work with researchers at NREL to develop screening tools to guide the siting of biomass processing facilities in ways that ensure equitable distribution of both the benefits and burdens of energy infrastructure.

Morgan Edwards,

“With this project, we have a new opportunity to center equity and community benefits early in the technology development process,” Edwards says. “We are designing interactive tools to quantify the direct benefits here in Wisconsin and throughout the U.S. and creating a blueprint for actively involving communities in identifying pilot sites for new, low-carbon products and infrastructure.”

In addition, art professor Darcy Padilla will photograph the scientists, communities and environments connected to the project.

Darcy Padilla Photo by: DARCY PADILLA

Padilla, who has documented the impacts of a coal-fired power plant on Native American communities in Arizona and of hydraulic fracking in North Dakota, says she is eager to work at the intersection of climate change, science and one of Wisconsin’s core industries, paper, which has seen more than a dozen mill closures over the past three decades, wiping out more than 21,000 jobs.

“Science is made by people, and it affects people,” Padilla says. “It’s usually the affected community that I’m looking at. With this project, it’s intriguing to see different facets at different places — to see it from a science perspective, to see where communities are right now, the possible impact on communities.”

The grant is one of five awarded by DOE’s Bioenergy Technologies Office as part of an initiative to advance the production of affordable biofuels and biochemicals that can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and help slow climate change.

Learn more about the project by reading the full story at the Wisconsin Energy Institute.