Urban foxes and coyotes learn to set aside their differences and coexist

On Dec. 15, 2015, a group of student veterinarians draw a blood sample from a sedated, 36-pound adult coyote caught at Curtis Prairie at the Arboretum as part of a research effort to study the behavior of growing fox and coyote populations in Madison. Pictured from left to right are veterinarians Miranda Torkelson, Kaylyn Goertz, Holly Hovanec and Melanie Iverson. The UW Urban Canid Project is led by Professor David Drake (kneeling at center). Photo: Jeff Miller

MADISON – Diverging from centuries of established behavioral norms, red fox and coyote have gone against their wild instincts and learned to coexist in the urban environment of Madison and the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, according to a recently published study in the journal PLOS One.

Lead author Marcus Mueller, a former graduate student in forest and wildlife ecology, and David Drake, his advisor and a professor in the department, found that over a two-year period, red foxes and coyotes they had radio-tagged were coming into close contact with one another. Some even established home ranges that overlapped.

The findings have implications for wildlife managers working to promote co-existence of species and mitigate conflicts between animals and people in urban settings.

“It gives us a better understanding of the types of habitats foxes and coyotes prefer to use in developed and residential areas,” says Mueller, who now owns a wildlife management company in Milwaukee. “This in turn can help us reduce the kinds of problems that can arise when wild animals and people come into contact.”

A fox wanders through a city street in Madison, Wisconsin. Photo courtesy of the UW Urban Canid Project

It also shows that these relatives of dogs have been able to carve out a successful niche for themselves in our own yards, parks and alleys, and are finding ways to coexist with each other to take advantage of this new resource-rich real estate.

“We found an instance where a coyote routinely visited a fox den over about a two or three week period,” Drake said. “But the fox and kits did not abandon the den, suggesting to us that they didn’t feel predation pressure from the coyote.”

In another observation from the study, a red fox and a coyote were seen foraging only meters away from one another and each minded their own business. The urban landscape, Drake suspects, is dissolving hostility between these two species and allowing them to move in close together without conflict.

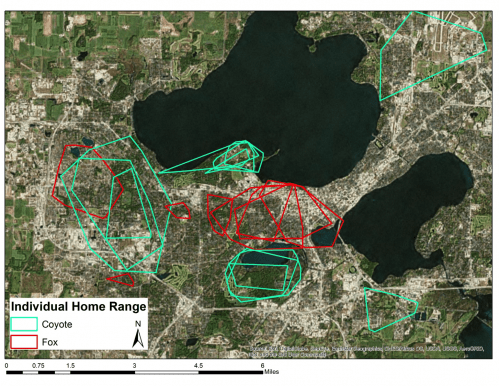

A map shows where foxes and coyotes roam in Madison, Wisconsin. The information was collected from GPS collars placed on the animals by David Drake, professor of forest and wildlife ecology, and his former graduate student, Marcus Mueller, as part of a study of urban canids. Marked in blue are the coyote home ranges, and in red are the fox home ranges. Courtesy of David Drake

“We think that this antagonistic relationship between coyotes and fox is breaking down and relaxing in the urban environment because the food is so abundant that they don’t have to compete for a limited resource like they do out in the non-urban areas,” Drake said.

This study was conducted in Madison, Wisconsin over a 27-square-mile area encompassing the UW–Madison campus, outlying residential neighborhoods, and some commercial and small natural areas. Drake and Mueller, with help from UW–Madison students and interested members of the public, trapped and radio-tagged 11 coyotes and 12 red foxes. The researchers triangulated the animals’ positions using a technology called telemetry once a week for five-hour periods at a time between Jan. 2015 and Dec. 2016.

Drake and Mueller classified the spaces the animals traveled through into five categories based on the amount of human development. This allowed them to determine both species’ preferences when it came to where to make their homes with respect to people and to each other.

When selecting their home ranges and establishing dens, coyotes preferred areas with a high proportion of natural space, such as the woods of the UW Arboretum and Picnic Point, instead of developed spaces. Conversely, red foxes opted for open and developed spaces to make their homes and generally avoided more natural areas.

Drake and Mueller’s study suggests that the propensity for red foxes to avoid natural spaces may be due to the coyote’s role as an apex predator (higher on the food chain). Because they are larger than foxes, coyotes get first dibs on where they call home, which is usually wherever they can be isolated and away from people.

However, studies of red fox in London show that even in a landscape devoid of coyotes, foxes still opt to build their cozy dens in more developed areas of the city. This suggests that red fox in Madison would still choose the same territories even in the absence of coyotes, Drake says.

A red fox spotted meandering east on North Charter Street, crossing over to the nook behind Ingram Hall where he found a warm sun spot, walked in several circles, and laid down to relax on a lazy Friday afternoon. Mason Muerhoff

On Madison’s west side, the home ranges of the foxes overlap with the coyotes. Drake suspects this is because Owen Park, the conservation space where the coyotes on the west side have made their home, is smaller than the spaces that the UW Arboretum and Picnic Point coyote packs occupy. This leads them to wander outside their territory and into developed areas, where foxes already live.

Both animals are crepuscular, or stalk about from sundown to sunup, to avoid human activity. But red foxes are less timid and have been known to den in high-traffic areas of the UW–Madison campus.

Because of the growing tide of canids and wildlife moving into the city, Drake established the Urban Canid Project to encourage citizens and campus visitors to record sightings of animals like red foxes and coyotes, which he hopes will one day replace the need for radio-telemetry tracking. This is time intensive for the scientists, who must search for a signal from the animals’ collars to locate them and then stay close enough to track their movements.

Drake has also invited over 500 community members over the past four years to come along with his crews when they are live trapping animals in the winter, and gives dozens of presentations around Madison each year.

“We are seeing a lot of coyote and red fox in Madison and we want to find out what’s different in the city that these animals can live in seemingly close proximity with each other when they can’t do that in rural areas,” Drake says

This study was funded by the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, the UW–Madison Graduate School, the Milwaukee County Parks Department., and private donations to a gift account for this study through the UW Foundation.