Photo gallery The 2023 winners: Cool Science Image Contest

Winners in the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s 13th annual Cool Science Image Contest include the first-ever look at how a fish organizes its immune cells, faraway galaxies whose light is being curved by supermassive objects, soybeans flashing blood-red beet colors and an invisible portrait of the first woman to win a Nobel Prize.

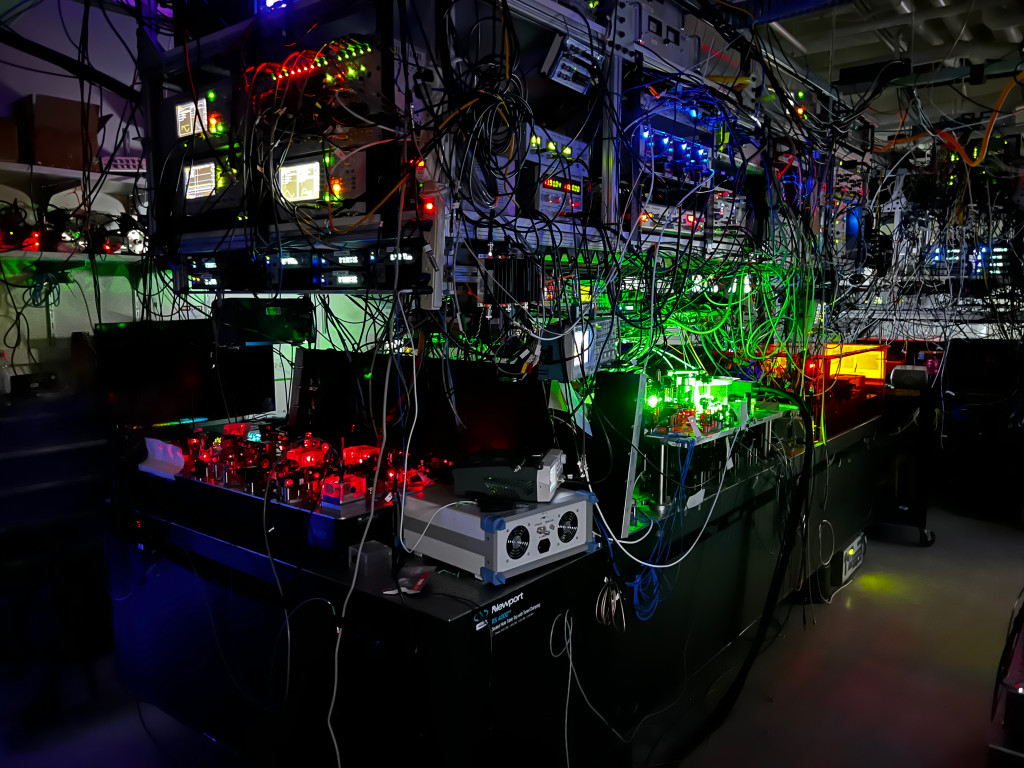

A panel of experienced artists, scientists and science communicators chose 12 winning images based on the aesthetic, creative and scientific qualities that distinguished them from scores of entries. The winning entries showcase the research, innovation, scholarship and curiosity of the UW–Madison community through visual representations of socioeconomic strata, brain cells snuffed out in Parkinson’s disease, the tangle of technology required to equip a quantum computing lab and a bug-eyed frog that opened students’ eyes to the world.

The winning images go on display this week in an exhibit at the McPherson Eye Research Institute’s Mandelbaum and Albert Family Vision Gallery on the ninth floor of the Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research, 1111 Highland Ave. The exhibit, which runs through the end of 2023, opens with a public reception at the gallery Thursday, Sept. 28, from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. The exhibit also includes historical images of UW science, in celebration of the 175th anniversary of the University of Wisconsin’s founding.

The eyes of a queen conch peer out nervously from an overturned shell in a seagrass meadow in the Turks and Caicos Islands. Conchs eat and recycle organic matter, an important role in seagrass habitats that are, in turn, important in stabilizing shorelines with their dense root systems. Robert Johnson, assistant professor, Integrative Biology Underwater camera

The Milky Way stretches overhead above a twilight sky, tinged pink by particulate thrown skyward by the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcanic eruption in 2022. Kaitlin Moore incorporated astrophotography in her dissertation, hoping to carve out a place for artistic interludes within environmental humanities and illuminate connections between persons and environments. Kaitlin Moore, graduate student, English Digital camera

The glow of red and green lasers and an array of supporting electronics fill a UW–Madison lab where physicists study the behavior of cesium atoms cooled within a fraction of a degree of absolute zero. The atoms could be used to store information in quantum computing systems. Jacob Scott, graduate student, Physics Digital camera

Like the radiation she studied, this portrait of physicist Marie Curie is invisible until revealed by the proper equipment — in this case, a polarizer, a filter that blocks all light waves except those oscillating in a certain direction. One polarizing filter on the back layer of the portrait organizes the light shining through to the viewer. That light passes through layers of colorless cellophane, which rotate the waves a little or a lot depending on the layer’s thickness. A second polarizing filter, held by the viewer, filters the light again, selecting light at the wavelengths that correspond to the intended colors of the portrait. The image above is as the portrait appears viewed through a polarizer. Aedan Gardill, 2023 doctorate recipient, Physics Cellophane

These soybeans are beet red thanks to beet genes added by researchers at the Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center — the largest public plant-transformation center in the country — alongside gene edits meant to alter characteristics like nitrogen use, herbicide resistance and stress response. If the seeds are magenta, it means the gene-editing machinery is still present in the plant, giving the researchers a visual indicator of where things stand in the gene-modification process. Ray Collier, scientist, Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center Guifen Li, molecular biologist, Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center Aimee Peickert, research specialist, Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center Edward Williams, scientist, Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center Rob Harnish, dicot program manager, Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center Digital camera collage

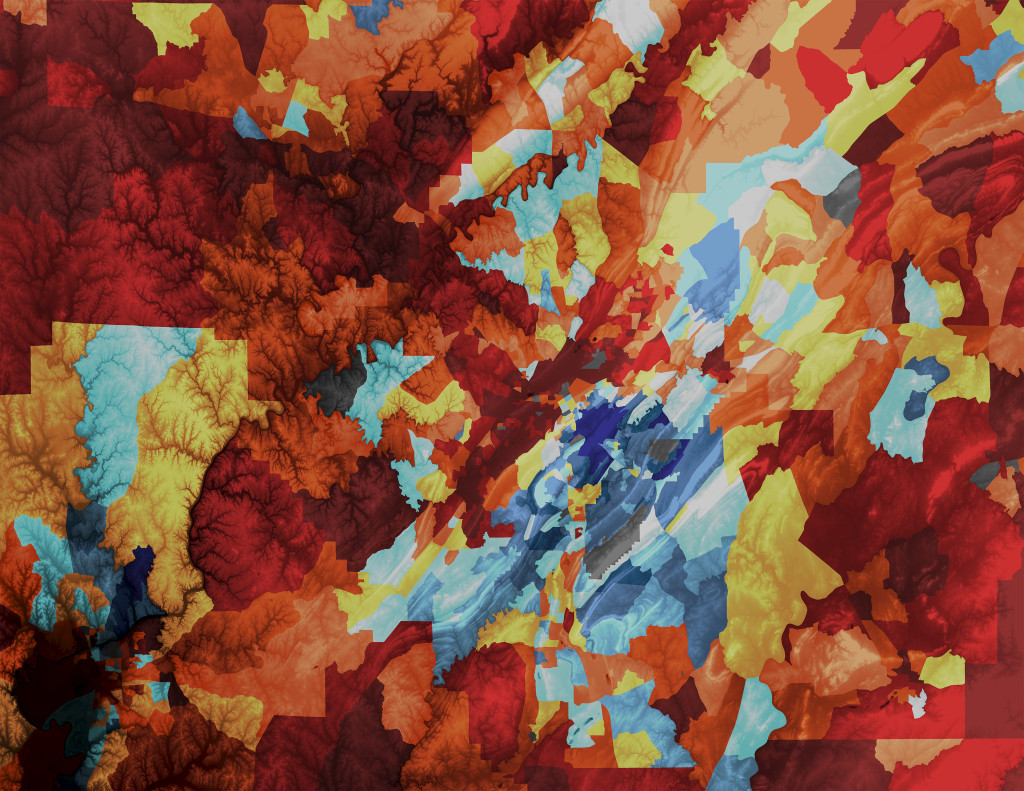

Layering measurements of socioeconomic disadvantage — a scale called the Area Deprivation Index created by UW–Madison’s Center for Health Disparities Research — at a neighborhood scale over a map gives researchers the opportunity to consider how geography may be affecting health outcomes. Luke Chamberlain, graduate student, Center for Health Disparities Research Nyla Thursday, graduate student, Center for Health Disparities Research Will Buckingham, director of geospatial operations, Center for Health Disparities Research ArcGIS, Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop

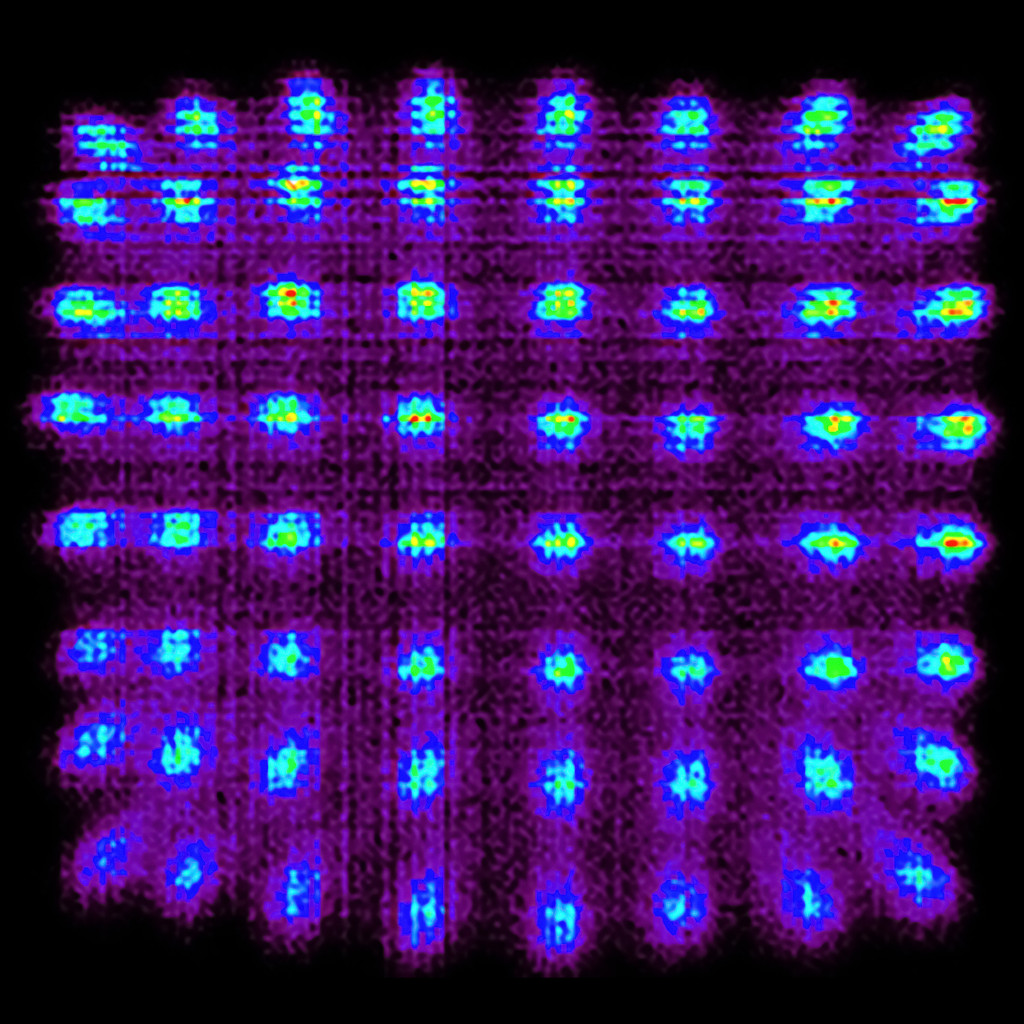

Scintillator crystals like these make PET scanners work by soaking up emissions from radioactive tracers injected into patients. The crystals — arrayed in multiple detectors — turn gamma rays into visible light, which the scanner uses to reconstruct three-dimensional images pinpointing the location of cancerous tumors or decreased blood flow in heart disease. Maxim Slesarev, neuroimaging technologist, Waisman Center PET scanner

Brenen Skalitzky snapped this photo of a red-eyed tree frog, an iconic resident of tropical forests in Central and South America, at a nature reserve in Sarapiqui, Costa Rica, during a UW–Madison experiential learning trip. Witnessing the biodiversity of other parts of the planet, he says, better prepares students to advocate for fragile ecosystems. Brenen Skalitzky, undergraduate student, Genetics and Genomics Digital camera

This swirling glow is the result of a drip of bleach into the substrate of a western blotting assay, a lab technique used for detecting proteins. In a typical western blot assay, the presence of target proteins is indicated by light, which is produced when the proteins trigger a reaction called oxidation — catalyzed by an enzyme from horseradish root — in which molecules of the assay’s gel substrate lose an electron to hydrogen peroxide. Bleach, however, is a strong oxidizer, and can put on the light show all by itself. Yifei Ren, graduate student, Biophysics Digital camera

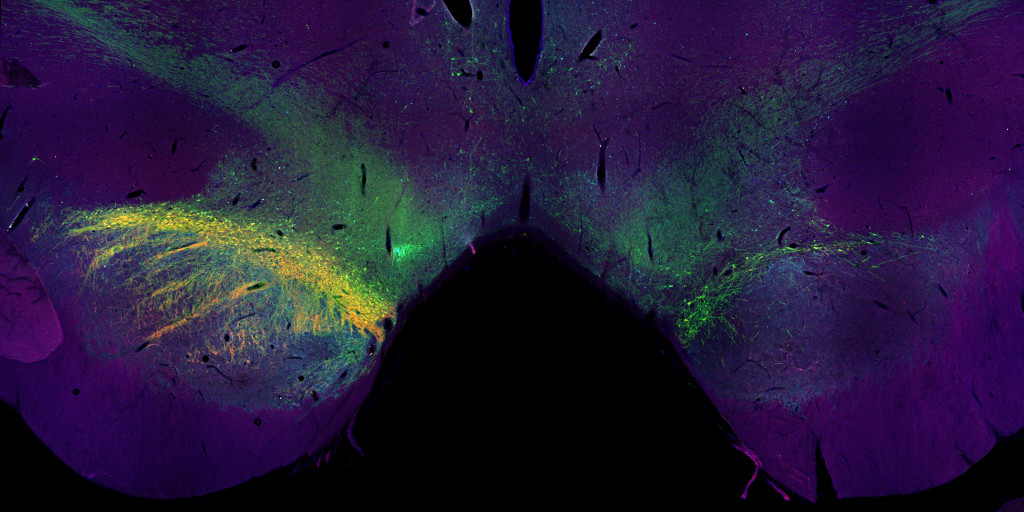

The tremors and motor-control problems experienced by Parkinson’s disease patients are caused by the death of brain cells called neurons that produce a signaling molecule called dopamine. The array of colors on the left side of this tissue sample from the brain of a cynomolgus macaque monkey should label many types of dopamine-producing neurons. The rainbow should arc in a mirror image on the right side of the brain, but this monkey — a model of Parkinson’s in human patients — has lost many of those neurons. Studying animal models of Parkinson’s like this one, as Professor Marina Emborg does at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, has led to stem cell treatments for Parkinson’s that relieved tremors in monkeys. Jeanette M. Metzger, scientist, Wisconsin National Primate Research Center Viktoriya Bondarenko, research specialist, Wisconsin National Primate Research Center Preethi Saravanan, undergraduate student, Biology Lindsey Neumann, undergraduate student, Neurobiology Marina E. Emborg, professor, Medical Physics Confocal microscope

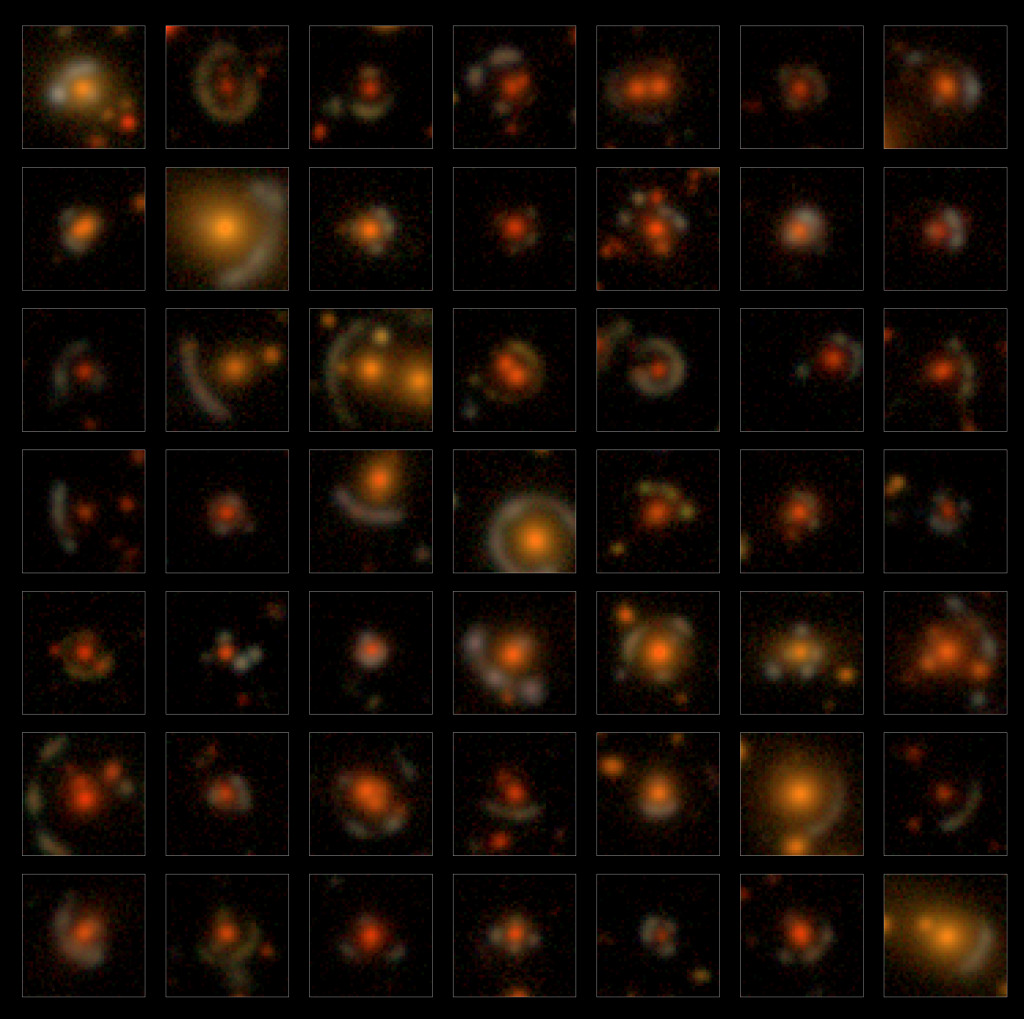

Each image in this collage is of an astronomical phenomenon known as a strong gravitational lens, in which the light from a galaxy or cluster of galaxies is curved by a massive object in the foreground. The light is distorted into bright arcs, exhibiting physics theorized by Albert Einstein. Strong gravitational lenses offer a way to study dark matter, difficult to detect but considered a crucial factor in the structure, evolution and fate of the cosmos. Jimena Gonzalez, graduate student, Physics Keith Bechtol, associate professor, Physics Dark Energy Survey Camera and Víctor M. Blanco Telescope

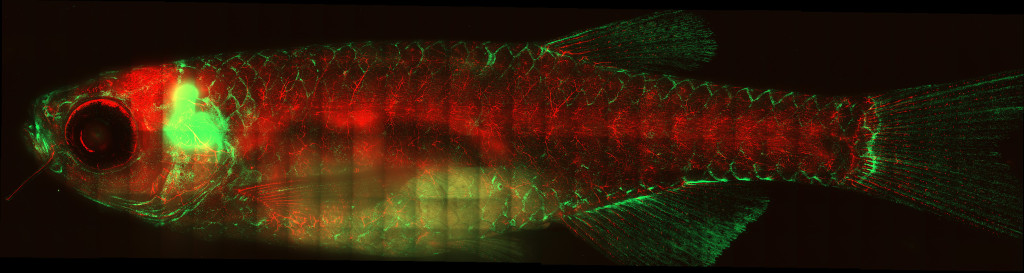

Seen for the first time under a microscope, a transparent zebrafish’s T-cells, which fight invaders like viruses and bacteria, shine green against the red of the fish's blood vessels, revealing the T-cells' organization into a networked immune system. Mammal immune systems are organized around lymph nodes, but non-mammal vertebrates like fish don’t have nodes or connecting vessels. This view of a fish lymphatic network may help improve wildlife vaccines and lead to a better understanding of the evolution of immune systems. Tanner Robertson, postdoc, Medical Microbiology and Immunology Zeiss spinning disk confocal microscope

The Cool Science Image Contest recognizes the technical and creative skills required to capture and create images, videos and other media that reveal something about science or nature while also leaving an impression with their beauty or ability to induce wonder. The contest is sponsored by Madison’s Promega Corp., with additional support from UW–Madison’s Office of University Communications.

Winning entries are shared widely on UW–Madison websites, and all entries are showcased at campus science outreach events and in academic and lab facilities around campus throughout the year. See last year’s winners.

The 2023 contest judges were:

- Steve Ackerman, professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and vice chancellor for research and graduate education

- Kevin Eliceiri, director, Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation

- Ahna Skop, professor of genetics

- Kelly Tyrrell, director of media relations and strategic communications, University Communications

- Craig Wild, videographer, University Communications