Stan Temple: A life saving threatened species

Stan Temple, emeritus professor of forest and wildlife ecology and senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation, is pictured in the snowy woods near the historic Aldo Leopold Shack in rural Baraboo, Wis., on Dec. 6, 2010.

Photo: Jeff Miller

It is an icy winter Monday, and Stan Temple, for the sake of a shortened semester, must cram two lectures into one for the 300 students in his iconic Extinction of Species course. The combined topic is nongovernmental (NGOs) and governmental organizations. The lecture has to be bare bones, stripped of the fantastic stories of a lifetime, fleshy yarns that illustrate the successes, failures and foibles of the groups that seek to influence the policies and practices of environmental conservation.

Pacing the dais, Temple slices and dices a complex conservation landscape, explaining the roles and influence of NGOs and governmental entities in preserving — or exploiting — nature. There is no telling if the students in Temple’s course, a class he created and has taught for nearly 30 years, have any sense of the experiential wisdom they are receiving.

For Temple, now a University of Wisconsin–Madison emeritus professor of forest and wildlife ecology, the constraints of the lecture are stifling, as he has a lifetime of astonishing experiences to share. He is full of stories. He could tell his students of scrapping with the World Bank to save a forest on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. Or he might relate a hasty midnight flight from the Caribbean island nation of Grenada in advance of the 1980s assault by U.S. Marines (on the very hillside where he and his students were working). Or he could talk about the hissed death threats sometimes directed at him, visceral reactions to his research on the ecological harm caused by feral creatures like goats, rabbits and cats.

“I’m not getting death threats anymore,” says Temple, taking the time to look back on the mostly excellent adventures of a career spent studying and saving threatened animals, birds in particular, and their habitats. As a UW–Madison wildlife professor, Temple is heir to the outsized legacy of Aldo Leopold and, until his retirement, held the chair occupied by Leopold and his intrepid successor, Joe Hickey, the wildlife biologist whose work helped put the nails in the coffin of the insecticide DDT.

Temple is pictured with his hawk, D.C., at Temple’s snow-covered property in rural Wisconsin in 1989.

Photo: University Archives

Species such as the California condor, the peregrine falcon and the Mauritius kestrel, all once on the brink of extinction, are recovering, their survival abetted by the conservation methods Temple helped pioneer. “At least I retired without any of the dozens of species I worked on going extinct,” Temple jokes. “Most are doing significantly better, even as more and more species become endangered.”

Thwarting extinction is not for the meek, as Temple’s experiences attest. His brushes with controversy and international intrigue — coups, invasions, political upheaval — were so frequent his mother, noting his postcards often came from backwater flash points, became convinced her son Stan was a CIA agent. Ironically, some who opposed his conservation initiatives spread that very rumor: “That was an underhanded way to demonize me and minimize my impact,” Temple explains.

Themes of conspiracy came naturally to Temple and his work. In the 1970s, his efforts to reintroduce the peregrine falcon attracted the attention of federal law enforcement agents who imagined Temple’s work was the perfect cover to breed, smuggle and sell the sleek raptors to rich Arabs. The feds, Temple avers, spent more money on surveillance — including helicopter sorties to cliff faces where falcons were being released — than was invested in the recovery effort.

Preserving rare plants and animals, Temple knows, can bring out the best and the worst in people. His plan to eradicate feral rabbits from Round Island in the Indian Ocean (where they had been seeded many decades before by the Royal Navy to provide food for shipwrecked sailors) provoked an angry outcry. “Here was this little biological gem of a place where nearly every plant and animal was found nowhere else. Animal rights groups decided they would rather see all these unique plants and animals go extinct than eliminate the rabbits that were destroying the place.”

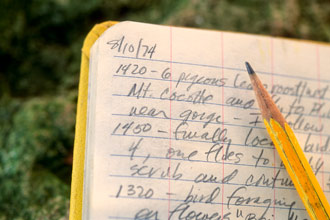

Pictured in 1994, a page from Temple’s field research notebook features handwritten notes from Aug. 10, 1974.

Photo: Jeff Miller

The rabbits were eventually removed, and Round Island’s endemic plants and animals are now recovering, Temple notes. But his encounters with ecological naiveté were not restricted to far-flung islands. Clearing invasive plants from his rural property, Temple was again cast as villain by ecologically clueless neighbors, prompting him to pen an often-cited essay, “The Nasty Necessity,” about the need to control invasive plants and animals for the sake of a biologically diverse world.

“What might my career have been like if we weren’t struggling to get through this binge of human population growth and consumption of resources with the world’s irreplaceable biological diversity still intact?” Temple muses.

However, the efforts of Temple and many others have brought species back; protected critical habitat; and raised public consciousness of our impacts on the natural world. Wisconsin has reclaimed signature species like the wolf, elk and trumpeter swan, the last another example of Temple’s handiwork. Nearly wiped out and absent from Wisconsin for almost 100 years, the swan again graces Wisconsin wetlands thanks to a state Department of Natural Resources reintroduction program designed by Temple.

While he is an expert, certainly, in the technical aspects of preserving and restoring species, Temple has done extraordinary work helping bring the facts and implications of extinction into clear public focus. “Over the course of his career at the University, Stan has played a critical role in defining the scope and magnitude of the extinction crisis and it has made a significant difference,” argues Leopold scholar and biographer Curt Meine. “When Stan arrived at Wisconsin, our understanding of the extinction crisis was rudimentary.”

Fortunately for many species like the California condor, Temple’s dogged persistence paid off. Saving the bird required capturing all the remaining wild birds and building a recovery effort around a captive breeding program. “That was very controversial,” Temple recalls. “Some thought bringing the last condors into captivity would hasten their demise. One famous biologist said he would rather see the condor go extinct with dignity than die in a cage. Well, now there are hundreds of them.”

“Stan embraces the challenges and delights of conservation,” observes UW–Madison botanist Don Waller, who together with Temple and zoology Professor Timothy Moermond established UW–Madison’s program in Conservation Biology and Sustainable Development in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. “His work could be controversial, but he never flinched in terms of standing up for what’s right in a conservation sense.”

While rare species tend to elicit controversy, it was a study of a common animal, feral cats, that sparked a hateful dustup. The 1990s study, which estimated that feral cats killed at least 7.8 million birds each year in rural Wisconsin alone, was a shocker but seemed to inspire more sympathy for the cats than the songbirds and other wildlife they so voraciously consumed. “It was tough dealing with the nasty calls and ugly hate mail,” recalls Temple. “I had no idea uncovering the facts would touch such a raw nerve with cat activists.”

The study was timely. The government was spending lots of money to encourage farmers to create habitat for wildlife, and Temple and his students were assessing the effects of the newly created habitats on Wisconsin’s vulnerable grassland birds. “These places were crawling with farm cats,” Temple recalls. “It struck us that you could be luring birds into an ecological trap, so the cat study was really a side project.”

Temple is pictured with his cat, Flynn, and a radio transmitter.

Photo: University Archives

But the results, effectively pinning the rap for millions of songbird deaths on cats, didn’t sit well with many, especially after Wisconsin’s Conservation Congress entertained the idea of designating feral cats as an unprotected species, which would have allowed landowners to control them. Although he played no role in the failed Conservation Congress initiative, Temple became an easy target. “I actually like cats,” Temple contends. “But I never had one until we did this study. He’s 21 years old now and he still likes me, although for the first seven or eight years of his life I made him wear a radio collar to provide data for the study.”

Growing up in Texas and Ohio, Temple’s world centered on wild places and the animals that inhabited them. Early on, Temple developed a passion for raptors and began practicing falconry in junior high school. “I was a big-time truancy problem then. I’d take any opportunity to skip school to go bird watching or fly one of my hawks.”

In adolescence, Temple secured a refuge at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where he was “adopted by the staff and given responsibilities beyond my years.” The opportunities included spending time with the iconic Rachael Carson of “Silent Spring” fame, whom he first met at age 10 on a bird hike. Another Cleveland Museum adventure left him stormbound in a shanty on a Lake Erie island where he found a copy of “A Sand County Almanac” and was introduced to the work of Aldo Leopold, who would become a personal hero.

Landing at Wisconsin after training at Cornell’s famous ornithology lab, was a stroke of good fortune: “Since I didn’t have a traditional wildlife background, few wildlife programs would give me a second look. This department was different. It’s been breaking new ground ever since Leopold started it.”

Temple’s iconoclastic ways, in particular his efforts to help found and lead the Society for Conservation Biology in the 1980s, undermined his reputation with some traditional wildlifers. “I was ostracized, especially when I became the society’s president. Some considered me a traitor.”

According to Meine, Temple played a linchpin role between traditional wildlife management and the newer interdisciplinary field of conservation biology. “Being a bridge person between emergent and traditional fields is a very difficult position to be in,” Meine explains. “Stan was an important figure in the coming together of conservation biology.”

The wounds from that paradigm shift have healed, apparently, as Temple was recently given The Wildlife Society’s second highest honor, honorary membership, in recognition of his life’s work. But Temple takes pride in his conservation biology work, noting that during his career the term ‘biodiversity’ became a household word.

After 35 years Temple remains active in his department, now the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, and is also a senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation in rural Baraboo. He trained a cadre of students who, notes Meine, wield global influence, including some who work for Temple’s erstwhile World Bank nemesis where safeguarding biodiversity is now infused into the business of fueling the economies of the developing world.

“He’s produced an amazing cohort of students over the course of his career,” says Meine. “And he continues to chart the course for the next generation by helping to guide conservation biology and connecting it to other fields of environmental science.”

Today, Temple is planning a new adventure, one that will enable him to continue walking in Aldo Leopold’s footsteps. In the late 1920s, Leopold visited some 200 communities in the Midwest to try to ferret out why traditional game species were disappearing, a phenomenon then attributed to overhunting. The upshot of that marathon was Leopold’s revolutionary emphasis on the central importance of protecting and restoring wildlife habitat. He summarized his approach in his classic “Game Management,” a text that is still widely consulted by conservationists.

“When I say I’ll be retracing Leopold’s footsteps, I am literally going to be doing just that,” explains Temple. “I’ll be revisiting many of the same communities to remind them of Leopold’s earlier visit and what his timeless ideas about living on the land without spoiling it mean today.”

For all of his accomplishments, Temple is guarded in his assessment of the prospects for the natural world.

“I’ve had to deal with some intractable issues during my career,” Temple says, taking the time to chat in a Russell Labs conference room under the steady gaze of an oil portrait of Leopold, binoculars at the ready. “And people often ask, ‘How do you manage to stay optimistic?’ I’m not, but I am hopeful.”