Professor’s film on Native American soldiers to air on PBS

As a United States soldier in the second decade of the 20th century, Edward DeNomie chased Pancho Villa and fought in all seven major battles of World War I. He took shrapnel in his ear and lost a lung in a German gas attack. He saw some of his best friends die, all while serving a country of which he was not a citizen.

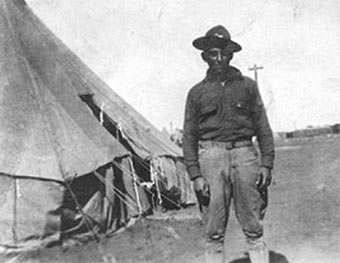

Patricia Loew’s grandfather, Pvt. Edward DeNomie (Bad River Ojibwe), 127th Infantry, 32nd “Red Arrow” Division, saw action in all seven major battles in which American Expeditionary Forces fought during World War I. Loew, an associate professor of life sciences communication, has produced “Way of the Warrior,” a documentary that explores the motivation of Native American soldiers to fight in the U.S. military, for a country that considered them outsiders.

Photo courtesy: Patty Loew

That is because he — like 12,000 other soldiers who volunteered for military service during World War I — was Native American.

Patty Loew, a veteran television journalist and an associate professor of life sciences communication, has long wondered what motivated men such as DeNomie, who also happens to be her grandfather, to fight for a country that considered them outsiders. Now, she has produced “Way of the Warrior,” a one-hour documentary that will air nationally on the PBS network in November, to explore these questions.

In chronicling the war stories of Native American soldiers from World War I to Vietnam, “Way of the Warrior” offers an interesting counterpart to Ken Burns’ seven-part series, “The War,” which was criticized by some for neglecting the contributions of minority soldiers in World War II. Like Burns, Loew uses historical footage, primary documents and interviews with veterans and their families to relate deeply personal tales of bravery, heroism and loss. But she also probes social stereotypes and aspects of tribal cultures that have made the experiences of Native American soldiers unique.

“Ironically, [my grandfather] turns out to be one of the best-documented World War I soldiers in history. But in many ways, he is an everyman. His experience is so representative of what most Native American soldiers faced.”

Patty Loew, associate professor of life sciences communication

Because Native Americans were not guaranteed U.S. citizenship until 1924, most Native American soldiers in World War I wore the uniform of a country that did not permit them to vote. Some chose to serve in guard units for a steady income, Loew says, but many others were motivated by tribal values of obligation, service and protection.

“There is a really heavy layer of warrior/service culture that exists in many Native American communities,” says Loew, a member of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. “Especially in protector clans such as the Bear Clan, you see many members volunteering to serve.”

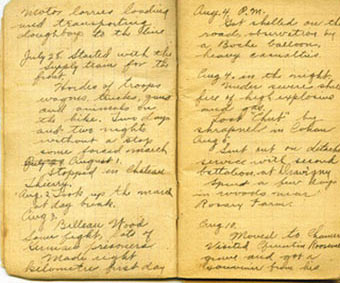

Although Loew was inspired by her grandfather’s experience to begin work on the documentary, she says she did not anticipate he would become a major part of the story. Fate, however, kept dictating otherwise. Shortly after Loew began research for the project, her cousin came across her grandfather’s wartime diary, which detailed the daily life of his infantry division as it moved through the battlefields of France. She later encountered footage and photographs of her grandfather’s unit in training and combat.

Entries from the diary of Pvt. Edward DeNomie in August 1918, written from the French front. The diary detailed the daily life of DeNomie’s infantry division as it moved through France during World War I. View a larger version of this image.

Photo courtesy: Patty Loew

“Ironically, he turns out to be one of the best-documented World War I soldiers in history,” Loew says. “But in many ways, he is an everyman. His experience is so representative of what most Native American soldiers faced.”

One common theme that emerges from Loew’s interviews is the danger many Native American soldiers encountered in combat. Loew says Native American soldiers were more likely to be placed in frontline positions, which she attributes to fantastical notions about Native Americans’ bravery and skill in the frontier.

“They were seen as super-warriors, who were supposedly extraordinarily brave and fierce,” she says. “Because of those stereotypes, Native Americans often saw some of the most dangerous duties in combat. They were disproportionately the ones walking point or jumping behind enemy lines.”

Documentary excerpt

Jim Northrup, a member of the Anishinaabe tribe who served in the Marines during the Vietnam War, tells of his family legacy of being “ogichidaa,” a Native American term that signifies one who protects and follows the way of the warrior.

This is a video story that requires the Flash 8 or higher player plugin. Download and install it.

Video courtesy: Patty Loew

And disproportionately dying. Loew notes that the casualty rate of Native American soldiers was five times higher than that of U.S. forces as a whole during World War I. Sixty percent of the men in her grandfather’s infantry unit died in action.

Yet Loew was struck by the rituals employed by many tribal communities to cope with such horrors. Her film describes elaborate traditional ceremonies that different Native American tribes staged to send off or welcome home soldiers. Those returning from war were sometimes given new names and ritual baths, which were meant to cleanse their souls of the atrocities they had witnessed. While some viewers may regard these ceremonies as purely symbolic, Loew perceives a deeper effect.

Loew

“Really, they are a form of group counseling,” she says. “They were a way to protect the community from this poisonous experience.” Indeed, she says the veterans she interviewed who underwent these rituals generally reported fewer problems with post-traumatic stress disorder in the years after their service.

Loew’s documentary will premiere nationally at 8 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 1. Wisconsin Public Television will air the film at 8 p.m. on Monday, Nov. 5. Check local listings for details.