Making LAZY plants stand up: Research reveals new pathway plants use to detect gravity.

A study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison has revealed a previously unknown pathway plants use to detect gravity and orient the direction they grow in. Publishing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study may one day open the door for improvements in crop cultivation.

Prior studies have already established that a suite of genes, nicknamed LAZY, control a pathway plants use for detecting gravity. In a typical plant, cells within the stem use LAZY genes to detect the force of gravity. The plant can then guide the stem to grow upwards, branches to grow outwards, and roots to grow downwards. These controlled directions of growth help a plant optimize its shape for energy production, stability and overall survival.

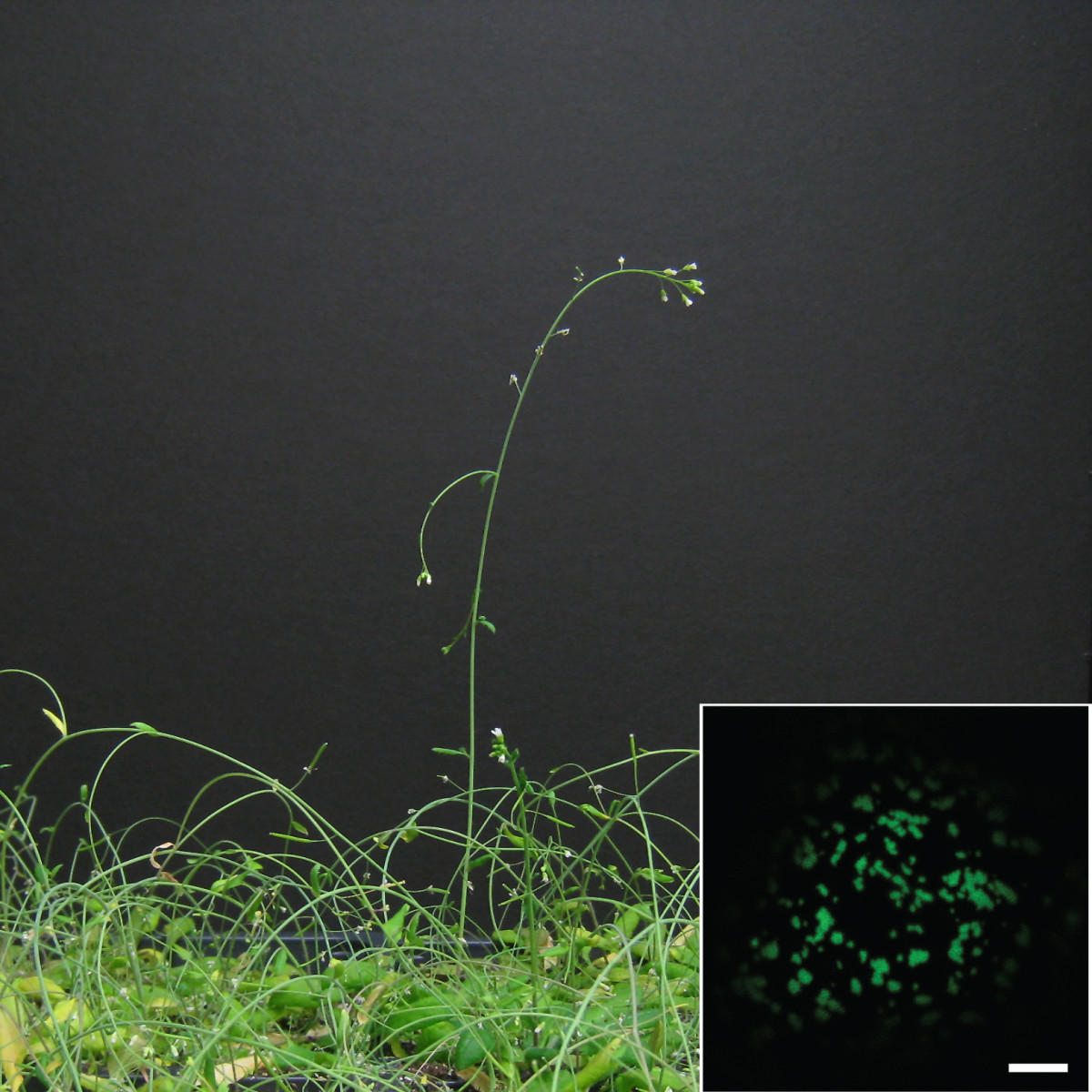

When LAZY genes are turned off, the mutated plant cannot properly orient itself. Instead, it sprawls along the soil surface, its stem bending in all the wrong directions. These specimens are aptly nicknamed LAZY plants.

Coauthors Edgar Spalding, an emeritus professor of botany, and Takeshi Yoshihara, a research scientist at UW–Madison, wanted to learn more about the genetics behind plants’ ability to detect gravity. Using Arabidopsis, a kind of plant commonly used in research, they turned off the plants’ LAZY genes and got to work.

“We decided to mutate these LAZY plants, this plant that doesn’t know which way it’s going, and hope we hit a gene that somehow corrects the problem,” says Spalding.

Research Moves Us Forward

Learn more about the impact of UW–Madison’s federally funded research and how you can help protect it.

Spalding and Yoshihara began randomly mutating the LAZY plants. They went through thousands of mutations before finally finding an unstudied gene called SLQ1, or suppressor of LAZY quadruple 1.

“Two wrongs can make a right sometimes,” Spalding says.

Spalding and Yoshihara found that when both LAZY genes and the SLQ1 gene are turned off, the resulting plant stem didn’t crawl along the soil but instead reached up into the air. They also found the genes controlling the two pathways are located in different parts of the cell and that the pathways function independently of each other.

Spalding says there are many reasons plants may need more than one way of detecting gravity. This SLQ1 pathway could be a backup process waiting in the wings to step in, should something malfunction with the LAZY genes. Further research is needed to investigate how the pathways function together, but Spalding thinks they likely work together to optimize the plant’s growth and fine-tune its architecture over time.

“Gravity guides plant growth through a more complicated mechanism than ever appreciated before,” Spalding says.

With more research, understanding how gravity influences the way a plant grows could help producers breed crops with finely tuned root, stem and branch architectures that make it easier for growers to harvest, maximize yield and grow more resistant crops.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (2124689).