In these microbes, iron works like oxygen

A pair of papers from a UW–Madison geoscience lab shed light on a curious group of bacteria that use iron in much the same way that animals use oxygen: to soak up electrons during biochemical reactions. When organisms — whether bacteria or animal — oxidize carbohydrates, electrons must go somewhere.

The studies can shed some light on the perennial question of how life arose, but they also have slightly more practical applications in the search for life in space, says senior author Eric Roden, a professor of geoscience at UW–Madison.

The steamy volcanic vent at Chocolate Pot hot spring in Yellowstone National Park, an iron-rich but relatively cool hot spring where a variety of fascinating microorganisms thrive without oxygen. Courtesy of Nathaniel Fortney

Animals use oxygen and “reduce” it to produce water, but some bacteria use iron that is deficient in electrons, reducing it to a more electron-rich form of the element. Ironically, electron-rich forms of iron can also supply electrons in the opposite “oxidation” reaction, in which the bacteria literally “eat” the iron to get energy.

Iron is the fourth-most abundant element on the planet, and because free oxygen is scarce underwater and underground, bacteria have “thought up,” or evolved, a different solution: moving electrons to iron while metabolizing organic matter.

These bacteria “eat organic matter like we do,” says Roden. “We pass electrons from organic matter to oxygen. Some of these bacteria use iron oxide as their electron acceptor. On the flip side, some other microbes receive electrons donated by other iron compounds. In both cases, the electron transfer is essential to their energy cycles.”

Eric Roden

Whether the reaction is oxidation or reduction, the ability to move an electron is essential for the bacteria to process energy to power its lifestyle.

Roden has spent decades studying iron-metabolizing bacteria. “I focus on the activities and chemical processing of microorganisms in natural systems,” he says. “We collect material from the environment, bring it back to the lab, and study the metabolism through a series of geochemical and microbiological measurements.”

The current studies focus on bacteria samples from Chocolate Pot hot spring, a relatively cool geothermal spring in Yellowstone National Park that is named for the dark, reddish-brown color of ferric oxide. Related studies deal with a culture obtained from a much less auspicious environment — a ditch in Germany. Both studies are online, in Applied and Environmental Microbiology and in Geobiology.

During the studies, Roden and doctoral student Nathan Fortney and research scientist Shaomei He explored how the cultured organisms changed the oxidation state — the number of electrons — in the iron compounds. They also used an advanced genome-sequencing instrument at the UW–Madison Biotechnology Center to identify strings of DNA in the genomes.

“More than 99 percent of microbial diversity cannot be obtained in pure culture,” says He, meaning they cannot be grown as a single strain for analysis. “Instead of going through the long, laborious and often unsuccessful process of isolating strains, we apply genomic tools to understand how the organisms were doing what they were doing in mixed communities.”

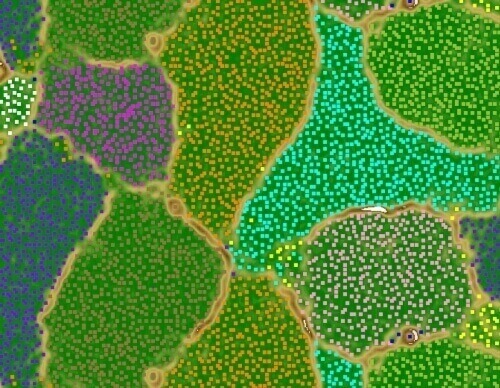

An abstract representation of the microbial community in a bacterial culture obtained from Chocolate Pot hot spring. The colored dots represent DNA fragments from each microbial variety; the fragments are clustered based on unique similarities within an organism’s DNA. Courtesy of Nathaniel Fortney

The researchers found some unknown bacteria capable of iron metabolism, and also got genetic data on a unique capacity that some of them have: the ability to transport electrons in both directions across the cell’s outer membrane. “Bacteria have not only evolved a metabolism that opens niches to use iron as an energy,” says He, “but these new electron transport mechanisms give them a way to use forms of iron that can’t be brought inside the cell.”

“These are fundamental studies, but these chemical transformations are at the heart of all kinds of environmental systems, related to soil, sediment, groundwater and waste water,” says Roden. “For example, the Department of Energy is interested in finding a way to derive energy from organic matter through the activity of iron-metabolizing bacteria.” These bacteria are also critical to the life-giving process of weathering rocks into soil.

Iron-metabolizing bacteria have been known for a century, Roden says, and were actually discovered in Madison-area groundwater. “Geologists saw organisms that formed these unique structures that were visible under the light microscope. They formed stalks or sheaths, and it turned out they were used to move iron.”

These test tubes show the cultures before (left) and after microbial activity. The bright orange in the left-hand tube is from amorphous iron oxides in the hot spring sediments. The grey surface layer in the right-hand tube is a different iron mineral, siderite, which is produced after about a week of activity. Courtesy of Nathaniel Fortney

Roden and He are geobiologists, interested in how microbes affect geology, but the significance of microbes in Earth’s evolution is only now being fully appreciated, Roden says. “Eyebrows rose when we contacted the Biotech Center three or four year ago to discuss sequencing: ‘Who are these people from geology, and what are they talking about?’ But we stuck with it, and it’s turned into a pretty cool collaboration that has allowed us to apply their excellent tools that are more typically applied to biomedical and related microbial issues.”

Some of the iron-metabolizing bacteria appear quite early on the tree of life, making the studies relevant to discovering the origins of life, but the findings also have implications in the search for life in space, Roden says. “Our support comes from NASA’s astrobiology institute at UW–Madison. It’s possible that on a rocky planet like Mars, life could rely on iron metabolism instead of oxygen.

“A fundamental approach in astrobiology is to use terrestrial sites as analogs, where we look for insight into the possibilities on other worlds,” Roden continues. “Some people believe that use of iron oxide as an electron acceptor could have been the first, or one of the first, forms of respiration on Earth. And there’s so much iron around on the rocky planets.”

Tags: biology, biosciences, geology, microbiology, research, space & astronomy