Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to dream in public

Gloria Ladson-Billings’ many efforts have led to new models for examining ways to reduce academic disparity between mainstream and minority students. Research linked to culturally relevant pedagogy has been used by scholars around the world as a framework, with her work cited more than 40,000 times, according to Google Scholar. Photo: Marcus Miles

Gloria Ladson-Billings didn’t grow up a dreamer.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” wasn’t a question kids in her Philadelphia neighborhood were asked. The goals for children were pretty simple: Graduate from high school and stay out of trouble. Maybe, just maybe, go to community college.

“Black working-class residents of West Philadelphia did not have the luxury of dreams,” Ladson-Billings says.

And yet, she has become a renowned scholar who has helped change the way teachers teach with her groundbreaking 1994 book “The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children.” She was the first black woman to become a tenured professor in UW–Madison’s School of Education in 1995.

This was never her dream. She didn’t even think to dream it. Not only does she dare to dream in public now, but she encourages, practically insists, others do as well.

Ladson-Billings formally retired from her position as the Kellner Family Distinguished Chair in Urban Education in 2018 after being on the UW–Madison faculty for more than 26 years. She had hoped to retire without giving a speech but that just isn’t possible when you’ve impacted so many — and when you’re the kind of speaker who takes the stage to “Hypnotize” by The Notorious B.I.G. as she did at a recent reception honoring her at Gordon Dining and Event Center.

Ladson-Billings formally retired from her position as the Kellner Family Distinguished Chair in Urban Education in 2018 after being on the UW–Madison faculty for more than 26 years. She had hoped to retire without giving a speech but that just isn’t possible when you’ve impacted so many — and when you’re the kind of speaker who takes the stage to “Hypnotize” by The Notorious B.I.G. as she did at a recent reception honoring her at Gordon Dining and Event Center.

Her talk, “Dreaming in Public: Renewing the Commitment to Education for Democracy,” walked the audience through her scholarship and the less likely road where it all began.

Dreams came at a cost. They made you vulnerable, to the laughter of others and the disappointment of wanting more than seemed possible.

“We were reluctant to share dreams because we saw so much disappointment,” she says.

It wasn’t that she and her friends weren’t smart; they were realists. They saw the common path of those around them, entering the work force, often in the same place their parents worked, rather than continuing their education. Many others joined the military. But a four-year college? That was for the children of parents who had gone to college, not the children of those with parents who may not have graduated from high school.

“New” clothes came from pawn shops or siblings and cousins who had outgrown them. Dreams were a nice idea, but the more immediate realities of paying rent and having food on the table were immediate and constant.

Her brother joined the Air Force. Ladson-Billings wasn’t sure what she should do but she knew she wanted something more than what was expected. She considered being a medical technician, mainly because it sounded “fancy” and you didn’t have to go to medical school. But she knew she loved writing.

Being the first black woman to become a tenured professor in UW–Madison’s School of Education was never her dream. She didn’t even think to dream it. Not only does she dare to dream in public now, but she encourages, practically insists, others do as well. UW–Madison School of Education

“I couldn’t figure out how to get paid to do it, and my family could not afford the luxury of me finding my writing voice,” she says.

Being a writer seemed like fiction. So she set out to become a teacher, earning her bachelor’s degree in education from Morgan State University in Baltimore in 1968 and master’s in curriculum and instruction from the University of Washington in Seattle in 1972.

While teaching wasn’t what she thought she’d end up doing, something changed after walking into a classroom and meeting students.

“It helped me understand that one of the most effective ways to affect democracy was through the classroom,” she says.

After a decade teaching in Philadelphia public schools and several years in California, she wondered why black students were not successful in school.

“I knew too many smart black people and their school outcomes just didn’t make sense,” she said.

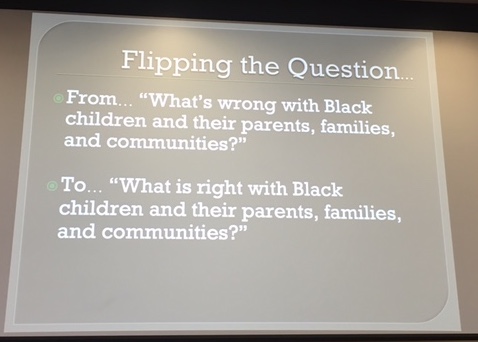

For so long, the question was: What’s wrong with black children? Did their parents not read to them enough? Was it their community? Their culture?

She went back to school, pursuing a Ph.D. in curriculum and teacher education from Stanford University, earning her degree in 1984.

In her research, she saw black children viewed as deficient and deviant. They weren’t seen as children with problems. They were the problem.

None of this made sense to her and it wasn’t helping improve learning outcomes.

Instead of asking what is wrong with black children, she began to ask what is right. That meant asking questions about their teachers and their classrooms. It meant taking a hard look at how children were taught. Photo: Käri Knutson

So she decided to flip the question. Instead of asking what is wrong with black children, she began to ask what is right.

That meant asking questions about their teachers and their classrooms. It meant taking a hard look at how children were taught. What could be done to help teachers succeed and help their students?

“I had two hunches. One was that black students in classrooms with skilled teachers could be academically, culturally, socially and civically successful,” she says. “My second hunch was that African American teachers, whose numbers were dwindling, were key to black student success.”

In 1989, she was giving a talk in New York on culturally relevant teaching and effective instruction for black students. It was a chance meeting after her talk that brought her to UW–Madison, as told in an issue of the School of Education’s Learning Connections.

“When I first heard Gloria speak, I could tell she had absolute clarity and a heightened consciousness about the problems and challenges facing students of color, and I believed that UW–Madison would be the ideal place for her to do this work,” said Carl Grant, who today is UW–Madison’s Hoefs-Bascom Professor of Teacher Education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction.

When the talk was nearly over, Grant ran out of the room. And as Ladson-Billings was wrapping up with a Q & A, he was standing in the hall, gesturing to her. The two met a few moments later and Grant told Ladson-Billings she needed to come work at UW–Madison.

“I’m not going to Wisconsin,” Ladson-Billings replied.

Grant was able to persuade Ladson-Billings to take a campus visit and deliver a presentation as part of the Wisconsin Center for Education Research’s Minority Visiting Scholars Program. After a long day on the UW–Madison campus — meeting School of Education faculty members, dropping in on classes and giving presentations — Grant took Ladson-Billings to a dinner at then-Chancellor Donna Shalala’s residence. Upon arrival, Shalala asked Ladson-Billings: “What do we have to do to get you here?” “I was caught so off guard,” says Ladson-Billings. “I said, awkwardly, ‘I already have a job.’

“And she said, ‘That’s not the question I asked you.’ I’m like, ‘Oh my God, who is this little lady?’”

She came to campus as an assistant professor specializing in social studies and multicultural education in the fall of 1991. She remembers fondly her time under Shalala’s tutelage, referring to herself and a group of black women faculty members at UW–Madison as “the Class of Shalala.”

The winters haven’t exactly grown on her, but the community has.

In 1989, as Ladson-Billings was wrapping up a Q & A in New York, Carl Grant was standing in the hall, gesturing to her. The two met a few moments later and Grant told Ladson-Billings she needed to come work at UW–Madison. UW–Madison School of Education

She has helped the Madison Metropolitan School District with various projects while constantly traveling the country, and the world, speaking to rapt audiences about applying critical race theory to the field of education.

You don’t have to stay if you don’t like it, she kept telling herself. And she certainly had opportunities to leave.

Harvard and Vanderbilt tried to lure her away for faculty positions, while Stanford and Michigan State considered her for dean posts.

“I never went out job hunting but got offers and calls,” Ladson-Billings says. “Every once in a while, if I’m down, I’ll pull out the letters Harvard was sending me and think, ‘They liked me. They really liked me!’”

For School of Education Dean Diana Hess, it’s hard to imagine campus without her.

“This institution would have been a very different place if she hadn’t been part of it,” Hess says. “She’s mentored and supported faculty, and worked to make school and campus more inclusive, more welcoming and more diverse.”

Her many efforts have led to new models for examining ways to reduce academic disparity between mainstream and minority students. Research linked to culturally relevant pedagogy has been used by scholars around the world as a framework, with her work cited more than 40,000 times, according to Google Scholar.

During her time at UW–Madison, she has edited 12 books, published 49 journal articles and 65 book chapters. She has served as an advisor for 53 doctoral students, including 21 African American women.

Many of her former students have gone on to become professors or teachers, passing her lessons on. Hess thinks about the students who are impacted by Ladson-Billings even though they’ve never met her or maybe don’t even know her name.

“I think we all hope to leave some kind of legacy, whether it’s through our work, or our family or our activism or relationship with others. We want to have an impact that lasts,” Hess says.

“Very few of us can match Gloria’s legacy. We are different, we are better because of Gloria and that is part of her legacy.”

In November, Ladson-Billings began serving a four-year term as president of the National Academy of Education, which supports research for the advancement of education policy and practice in the United States. Photo: Sarah Maughan

Appreciative words were shared on a screen before her recent campus talk, illustrating how she has inspired:

“While in undergrad at Morehouse College, all these aspiring black men were given a copy of ‘Dreamkeepers’ by Dr. Billings. Her book reshaped our vision of education and ignited a drive for using education to build bridges into the American dream. Now as a judge, her leadership continues to ignite my passion and believe in every child’s endless capacity for learning the need for cultural innovation so systems can meet the diverse educational dreams of our now generation. She is truly a divine light.”

“Gloria: Your voice of reason, inclusiveness and humanity resonates in my mind and hopefully has been passed on to my own students.”

“We need more Gloria Ladson-Billings in our lives. In our state and nation today, there are some toxic forces at work persuading us to position our schools as broken, our teachers as incompetent, our families as neglectful, and our children as criminals. GLB has provided us with perspectives that dismiss those fallacies and effective strategies for addressing those areas in desperate need of growth. Our children need to feel love, belonging, and recognition of their individual and collective gifts in order for them to thrive. We can do this better in our schools and communities. Let’s get to work ya’ll.”

“As the first African-American woman to be tenured in the Department of Curriculum & Instruction at UW–Madison, Gloria has taught me that hard work and dedication pays off.”

“She has changed my life. Her love, friendship and support are immeasurable.”

“I want to be just like you when I grow up!”

Even though she’s officially retired, her work isn’t stopping. In November, Ladson-Billings began serving a four-year term as president of the National Academy of Education, which supports research for the advancement of education policy and practice in the United States. Its members are a select group of education experts from around the world.

Her accolades are numerous. In 2018, she was ranked No. 3 in Education Week blogger Rick Hess’ annual ratings of the most influential education scholars in the U.S. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences elected Ladson-Billings to its 2018 class of members.

It’s not the books or awards that she thinks about.

“They mean nothing to the everyday realities of black children who are abused and violated in our schools,” Ladson-Billings says.

It’s about the students. And it’s about all of the people who will continue asking what is right with black children instead of what is wrong.

“They all represent my real legacy,” she says. “They are the dream I had in public and they are our best hope for a true democracy.”

WATCH: Gloria Ladson-Billings on being an “impact player.” UW–Madison School of Education video

This story is part of the UW Women at 150 series marking the 150th anniversary of the first women receiving undergraduate degrees at the university. Over the course of this academic year, University Communications will feature stories that celebrate the accomplishments of women at UW–Madison through the decades and recognize the challenges that remain, as well as the ways our views of gender have evolved and expanded.