Folklorist (and Grammy nominee) Jim Leary reflects on studying, sharing Midwest culture

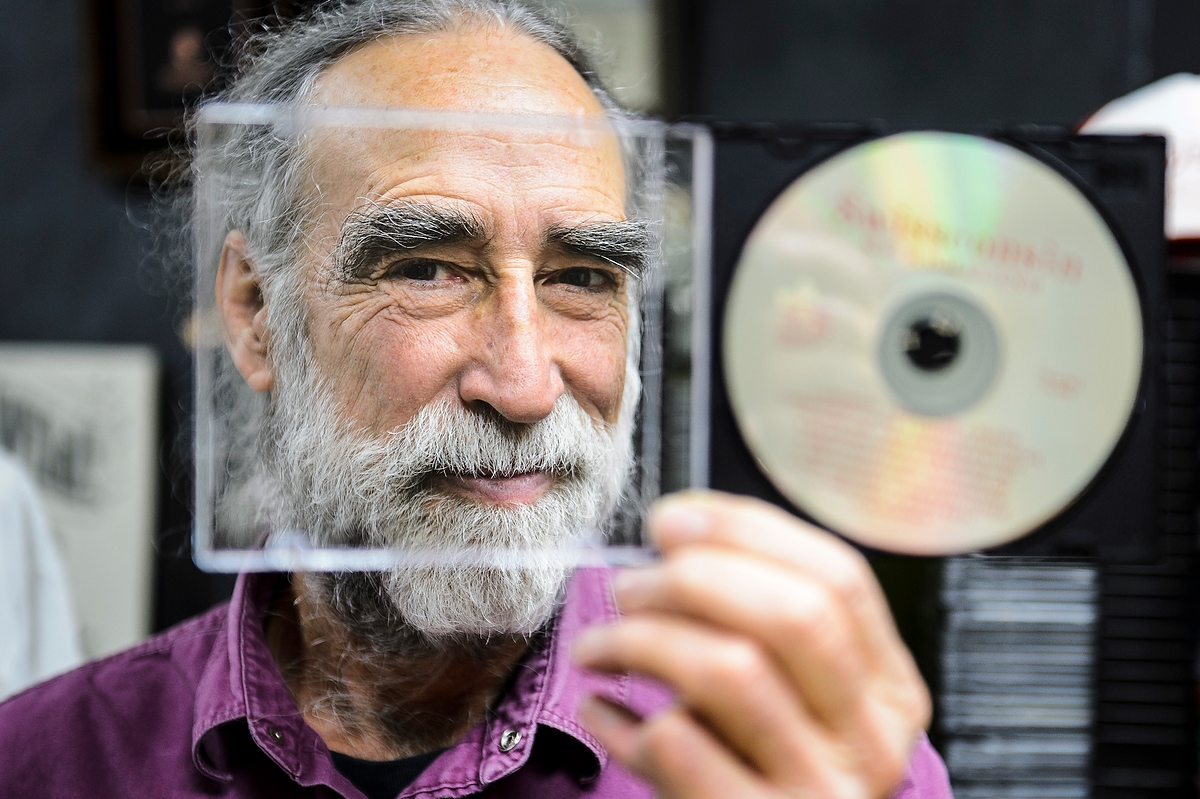

Soon-to-retire faculty member Jim Leary, professor of folklore and Scandinavian studies, peers through the liner-note section of a CD case in his office at Sterling Hall. Leary was recently nominated for a Grammy Award in the category of “Best Album Notes” for his work on the book and five CD/one DVD project “Folksongs of Another America: Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest, 1937-1946.” Photo: Jeff Miller

With his bushy gray hair and sturdy boots, Jim Leary looks true to his origins in Wisconsin’s north woods: Rice Lake, to be exact. It’s appropriate; as a professor of folklore and Scandinavian studies, Leary has brought Wisconsin and the Upper Midwest into the classroom since he began teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1984. He also co-founded and directed the Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Culture, cataloging everything from holiday traditions to Ole and Lena jokes.

“At heart, I think I’ve always been a folklorist,” he says, and he’ll continue even after retiring at the end of the fall semester. His many projects include ongoing fieldwork within the rich culture of ironworkers across the Midwest.

As Leary prepares to leave his classes behind, he can add Grammy Award nominee to his list of accolades, with a recent nomination for “Best Album Notes” for his work on “Folksongs of Another America: Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest, 1937-1946.” The sprawling book, CD and DVD project, co-produced by the UW Press and Dust-to-Digital Records, includes songs in more than 25 languages with full original lyrics and English translations.

Leary shared some thoughts on his career and his field with Inside UW:

How has the treatment of folklore and vernacular culture changed throughout your career?

Folklore is fundamentally grassroots culture, especially those parts that are expressive or have this artistic shape. Sometimes people think that the spread of mass media and the Internet are going to drown out regional culture. People at the grassroots level have taken hold of that.

I found that people who didn’t have a lot of higher education – not people you would associate with the digital generation, but rural or older or working-class people in cities – were interested in regional or ethnic music. They started to use the web fairly early; they’re connected through YouTube or different websites.

Among younger people, I’ve been able to share a lot of historic field recordings, and they’ve recorded new versions, or it’s sparked them to discover and learn from Finnish or Polish musicians in their own communities.

Why is folklore important academically, not just as something to enjoy or share?

I didn’t know there was such a thing to study as folklore until somebody told me. You need to have a presence at the university because that’s where young people are, trying to discover the world around them.

It’s typical for students to come in thinking of folklore as something that their ancestors had but they don’t – or that it’s long ago and far away. It also exists in the here and now. Those students have often been pretty excited to discover the vibrancy of their own cultural traditions.

Universities typically have been fascinated by high-culture productions: the stage, cinema, concert hall and art gallery, and the people who contribute to these somewhat refined or avant-garde productions. Nonetheless, there are traditions of storytelling, handwork, customary practices, songs, music, dance and food that come up out of the grassroots level. Often they inspire high art, but they have beauty and integrity in their own right.

Folklorists can create high quality, lasting records of these fundamentally human forms of art.

You’re a mainstay of our Experts Guide. What are some memorable questions or topics you’ve fielded?

I like the one about how we came to be known as the Badger State. The popular conception is that miners in southwest Wisconsin “burrowed into the sides of hills like badgers.” There’s little evidence that that term was in use until at least 40 or 50 years after they settled in the region.

The term is much more likely to have come from working-class people in the British Isles in the early 19th century. For immigrant miners from Cornwall, Ireland, Wales, and Yorkshire, “badgers” meant dangerous ruffians – of the sort that flourished in Wisconsin’s early mining communities.

What are some of your favorite tidbits of Midwestern lore?

I offered expert testimony in 1991 to the Legislature when the polka became the official state dance. There are more varieties of the polka in Wisconsin than anywhere else in the world because of the configuration of people who came here at a time when the polka was the hot dance form. Not just the European groups, but the Mexican polka and the fusion of African American jitterbug dance styles with elements of Polish hop polka dancing.

I also like that Wisconsin was the last state to comply with Prohibition: the last state to shut down its breweries, and the first to start them up again.

What work are you most proud of?

My work is all interrelated and has been dedicated to documenting and recognizing the ubiquity, variety, and worth of rural and working class peoples in the Upper Midwest: indigenous or immigrants (and their descendants), delivered through media or exhibits and festivals.

I’ve been doing this work since the 1970s, mostly on a shoestring. So I’m proudest of having hung in there long enough to have built up to completing a project as complicated, daunting, regionally-rooted and satisfying as Folksongs of Another America – especially since it’s not only been recognized by people throughout the Upper Midwest but all across the United States and in Europe.

Through it all, I’m lucky that Janet Gilmore – my spouse, partner, and fellow folklorist – has been willing to walk a sometimes hard and twisting road.

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.