Diet, aging study gains $7.9 million grant

A pioneering long-term study of the links between diet and aging in monkeys will continue through 2011 with the help of a new $7.9 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

First initiated at the National Primate Research Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1989, the study examines the effects of a reduced-calorie diet on the aging process and health of 76 rhesus monkeys. It is one of only two long-term studies of its kind, and during the course of 16 years has shown that a nutritious but reduced-calorie diet has multiple benefits for health and aging.

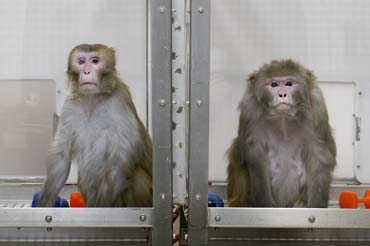

A pioneering long-term study of the links between diet and aging in monkeys will continue through 2011 with the help of a new $7.9 million grant from the National Institutes of Health. The study, led by Professor Richard Weindruch at the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and first initiated at the National Primate Research Center at UW–Madison in 1989, examines the effects of a reduced-calorie diet on the aging process and health of 76 rhesus monkeys. Pictured from the study sitting in animal cages are, left to right, rhesus monkeys Canto, on a restricted diet, and Owen, a control subject on an unrestricted diet.

Photo: Jeff Miller

The project, according to Richard Weindruch, the UW–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor who has led the research since 1994, is in a critical phase as the monkeys in the study are entering late middle age, which for rhesus macaques is their early to mid-20s. In captivity, rhesus monkeys can live up to 40 years.

Late middle age, Weindruch notes, is the time of life when a host of age-related conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, cognitive deficits and arthritis, among other things, begin to manifest themselves. This is true, he says, for both monkeys and humans.

“This is a very interesting time in the study,” says Weindruch, who also is an investigator at the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital. Because the animals have reached this stage of life, “it’s show time for dietary restriction.”

At this point in the study, the disparities between the monkeys on a diet reduced in calories by 30 percent and those allowed to eat as much as they wish are clearly evident. “Most importantly, we’re starting to see the separation of the survival curves,” Weindruch says, noting that 90 percent of the animals who began the study on a reduced diet are still alive, while only 70 percent of the animals allowed to eat freely have survived to this stage.

Of those animals who have died, most have succumbed to the same age-related conditions that kill many humans with colon cancer claiming the most, and diabetes and heart disease also taking a high toll. Says Weindruch: “Whether these trends will continue, time will tell.”

The idea that fewer calories can extend lifespan and improve health has a long experimental history. The notion has been tested in animal models ranging from spiders and mice to, more recently, fledgling studies in humans.

But the rhesus macaques in the Wisconsin study, according to Weindruch, offer perhaps the best window into a phenomenon that is the only proven dietary way to extend lifespan. Rhesus macaques have much in common with humans, including a similar genetic makeup and susceptibility to many of the diseases and conditions that affect human health.

The animals on a restricted diet exhibit 70 percent less body fat, and the fat tissue itself, Weindruch notes, is very different from the fat tissue in the control animals, those allowed to eat freely. His group has also observed that the animals that eat less have less insulin in their bloodstreams and less insulin resistance, which are opposite to increases seen in these hallmarks of type 2 diabetes.

“So far, we’ve had complete protection from type 2 diabetes,” Weindruch explains. “Normally, 30 percent of the animals in a research colony will exhibit type 2 diabetes.”

The new NIH grant will enable to project to add at least one new dimension, according to Weindruch: studies of brain structure and function as the animals age.

The new work is being coordinated by Sterling Johnson, an assistant professor of medicine, and will employ high-resolution MRI to assess structural changes as the monkeys in the study age.

The cognitive and functional abilities of the brain decline with age, Johnson says. Using techniques that involve such things as touch-screen computers and other methods of assessing brain function, Johnson and his colleagues will explore the functional changes that occur in the monkeys as they grow old and determine whether diet restriction affects cognitive aging.

“We’ll be looking at executive abilities, their abilities to make complex decisions as well as motor speed,” notes Johnson.

Tags: aging, biosciences, research