Campus exhibit reckons with institution’s history, lifts voices of marginalized

Attendees discuss the Public History Project at Monday’s opening-day event for media. From left to right are Micaela Sullivan Fowler, history of health sciences librarian; Kacie Lucchini Butcher, director of the Public History Project; Taylor Bailey, assistant director of the Public History Project; and Rev. Alex Gee, CEO of the Nehemiah Center for Urban Leadership Development and senior pastor of the Fountain of Life Covenant Church in Madison. The Public History Project and the exhibit seek to better understand the university’s history of bigotry and exclusion, including inequities based on race, gender, religious beliefs and more. Photo: Jeff Miller

An exhibit that uncovers and gives voice to those who experienced and challenged bigotry and exclusion at the University of Wisconsin–Madison opened Sept. 12 on the university’s campus.

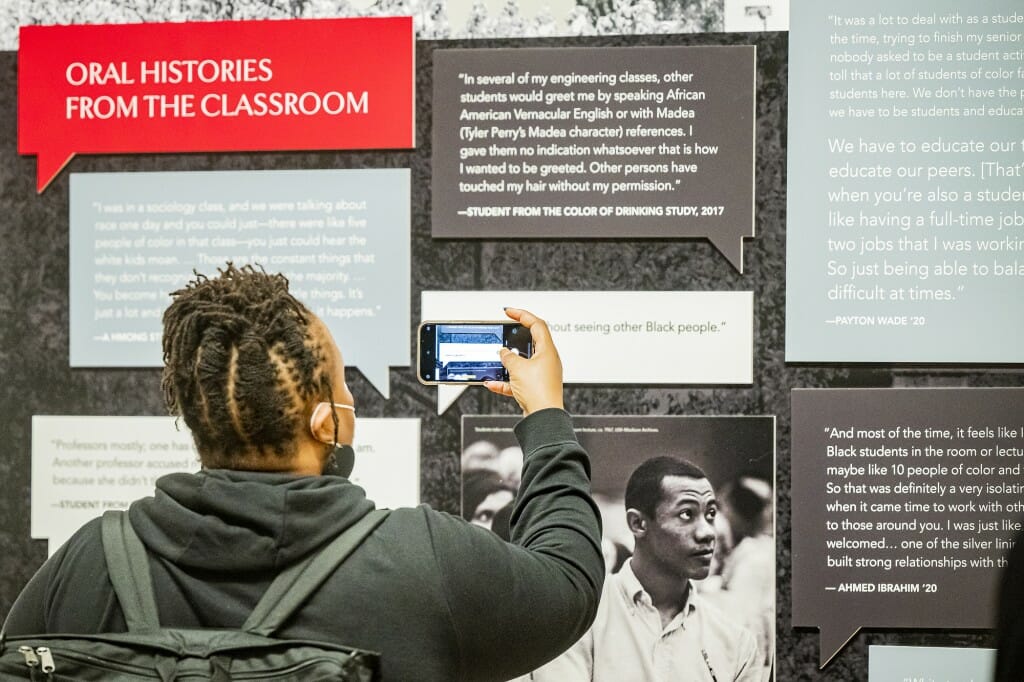

Spanning nearly 175 years of history, “Sifting and Reckoning: UW–Madison’s History of Exclusion and Resistance” brings to light stories of struggle, perseverance and resilience on campus. Archival materials, photographs and oral histories illuminate unseen and under-recognized histories in the exhibit, which will run through Dec. 23 at the Chazen Museum of Art.

“This is an important and historic day for UW–Madison,” said LaVar Charleston, deputy vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, at an opening-day event for media. “With the opening of the ‘Sifting and Reckoning’ exhibit, we are taking a significant step toward a fuller understanding of who we are as an institution.”

The exhibit encompasses three years of work by the Public History Project. The project grew out of a campus study group — commissioned in response to the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia — that looked into the history of two UW–Madison student organizations in the early 1920s that bore the name of the Ku Klux Klan.

In compiling its report, the study group identified a broader pattern of exclusion. It concluded that the history the UW needed to confront was not the aberrant work of a few individuals or groups but a pervasive campus culture of racism and religious bigotry that went largely unchallenged in the early 1900s and was a defining feature of American life in general at that time.

The study group recommended that an effort be made “to recover the voices of campus community members, in the era of the Klan and since, who struggled and endured in a climate of hostility and who sought to change it.” Rebecca Blank, chancellor at the time, commissioned the Public History Project as one of several responses to the findings.

The university hired Kacie Lucchini Butcher, a public historian and award-winning museum curator from La Crosse, Wisconsin, to lead the project.

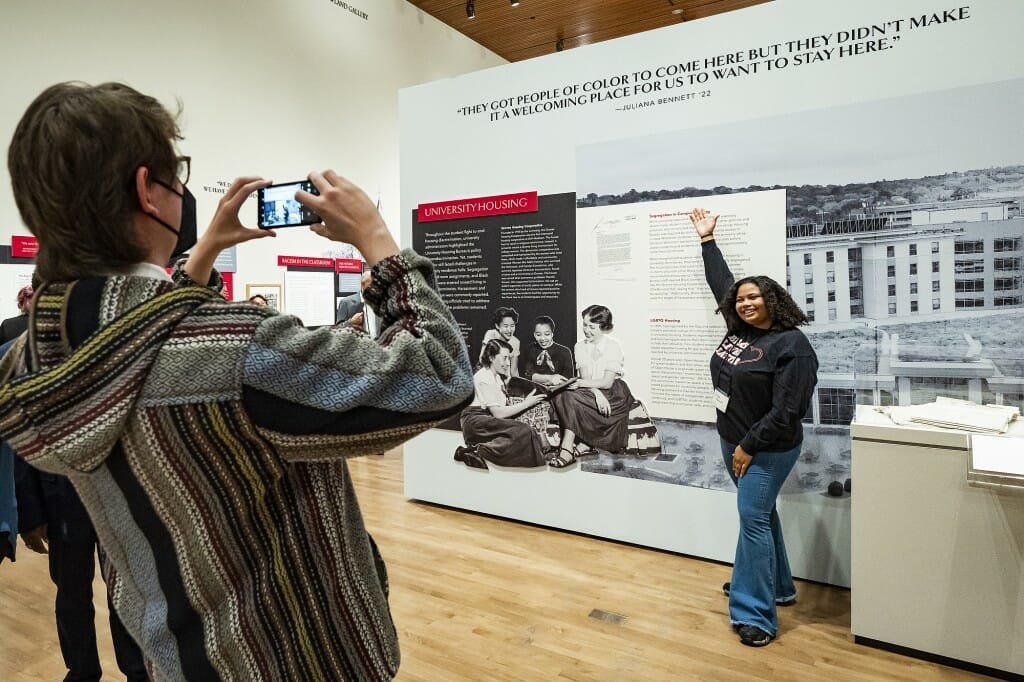

The exhibit includes photos from protests over the years that aimed to right wrongs. Photo: Jeff Miller

“Public history, at its simplest, is history written and made accessible for the public, for the people of our community,” Lucchini Butcher said at Monday’s event. “While many other universities have looked into their histories, no others have made public engagement the center of their work. This project has. All of our work, including this exhibition, was focused on the public, on our community, and how best to make this work accessible to them.”

John Zumbrunnen, a political science professor who serves as vice provost for teaching and learning, said the Public History Project will provide instructors with more material and more ways to engage students critically and honestly with questions of fundamental importance to UW–Madison, our communities and the nation.

“That kind of critical, honest engagement brings personal growth and intellectual growth,” said Zumbrunnen, who also spoke Monday. “It isn’t always easy — in fact, it is often quite challenging — but asking hard questions, including hard questions about ourselves and this university that we love, is what great universities do, and what the foundational commitments of this university in particular call for from faculty, staff and students.”

The Public History Project is part of a broader collection of efforts to create a more welcoming and inclusive campus, Charleston said. He expects the project will intensify and deepen discussions that already are happening on campus around issues of diversity and inclusion. And he hopes the project will inspire new ideas for how students, employees, alumni and the broader community can take active roles in creating change and achieving a more equitable UW–Madison.

“I hope people will come away with a renewed sense of pride in UW–Madison for being transparent and honest about its past and for making significant strides in many areas,” Charleston said. “I hope people will have a greater sense of ownership in UW–Madison and a greater sense of belonging, and that they will be inspired to continue working toward our vision and our goals for every Badger.”

A companion website (reckoning.wisc.edu) provides viewers with an immersive online experience, including materials that expand on the physical exhibit. The Fall 2022 Campus Climate Progress Report details some of the most recent ways UW–Madison is working to make sure all students feel safe, welcome and respected on campus.