Barley experiment reveals plant science to fifth-graders

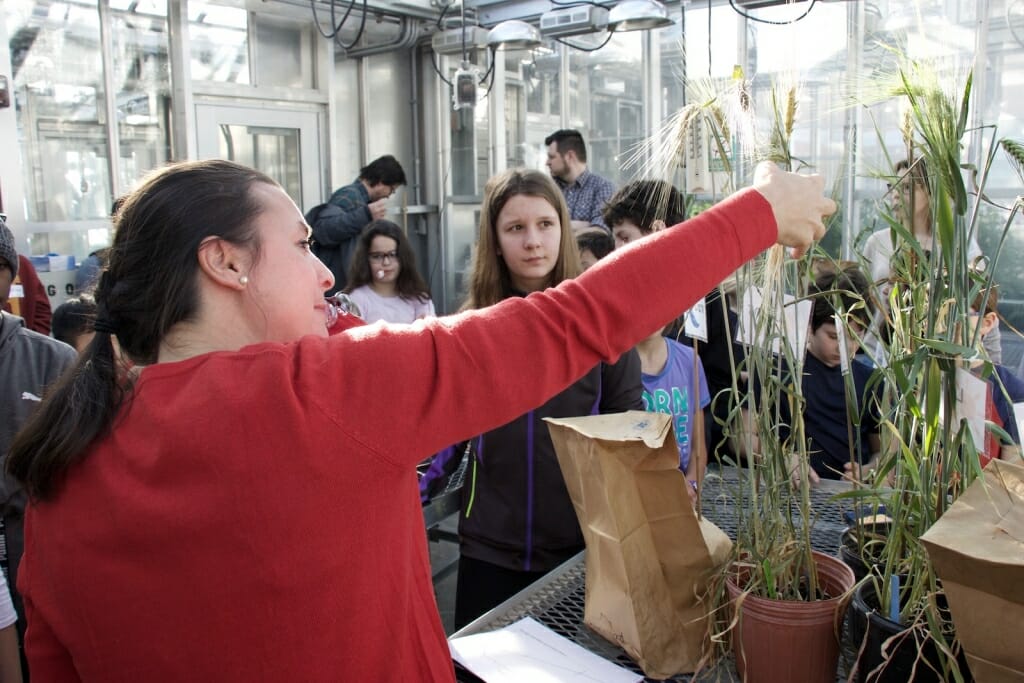

Fifth-grade students from Middleton visited a University of Wisconsin–Madison greenhouse on March 12, as part of a months-long project that used plant growth as a mechanism to explore science, math and environmental topics.

The student engagement is part of a national effort to breed “naked” barley, meaning barley without the indigestible hull, or seed coat. As researchers work on the genetic, agricultural and economic aspects of the new barley, fifth graders at Kromrey Middle School have been performing their own experiments.

The goal is to use plant breeding as a platform for science education, says Lucia Gutierrez, an assistant professor of agronomy at UW–Madison.

“The students are working on a tailored science curriculum that includes the use of naked barley as a model to understand genetics, plant breeding, and the interactions between plants and their environment,” says Gutierrez, who also has an appointment at Gutierrez. UW–Madison extension.

The class originally visited UW–Madison in December with their teacher, Maria Nygard, and planted experimental barley plants in the Walnut St. Greenhouses

The $2-million project, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture – Organic Research and Extension Initiative, and co-directed by Gutierrez, included researchers at Oregon State University and other universities, is trying to breed out barley’s hull (seed coat) and craft a productive, efficient and profitable barley suited to organic production.

“A big part of 5th grade science is the emphasis on using controls and variables in scientific experiment,” says Nygard, after the discussion in the greenhouse spent some time on variables, especially in regard to watering. How much water did you use? How often did you water? Did using hot or cold water make a difference?

And since this is fifth grade: Did plants grow better in water, Classic Coke or Diet Coke?

After Nygard asked the students about “the autopsy,” the discussion veered toward informed speculation. Perhaps the roots stuck to the pot because it was too small – or had something to do with the watering schedule.

“It’s nurturing their love of science, and they are having fun,” Nygard said. “Hopefully, one of them may go into a field that was not on their radar. And they will get to take some seeds home. Maybe they will grow some barley and bake something for the family.

“Any time you can bring children into a real-world environment, learning becomes so much more meaningful,” Nygard said. “Here, you are learning from some of best and brightest in the country.”

Alexa, who already grows tomatoes, radishes and carrots, has learned one important lesson for any budding scientist. “It’s okay to fail. If they don’t grow, you still get something from the experience. I raised mine in the dark, and they shriveled up. So I learned what not to do.”

To ensure that the barley strains crafted by the adult scientists are useful, the project includes farmers, bakers, chefs and millers. “Industry is involved in trying get this new barley out there,” said Gutierrez, “and it also includes brewers and malters.”

The major industries that use barley – brewers and livestock farmers – need not remove the hull, but the ultimate objective of the USDA project is an organically grown crop that can meet all three needs at once. “If we reach that goal,” says Gutierrez, “that will give farmers the flexibility to use the same plant for food, brewing and feed.”

Globally, barley is a much smaller crop than wheat, but they have similar roots. Starting about 10,000 years ago, barley and wheat were bred from wild plants, and became some of the first crops in the “fertile Crescent” of the Middle East.

Unlike wheat, barley still has a seed coat. “Wheat lost its coat almost 10,000 years ago; we are confident it won’t take us that long for barley,” Gutierrez says.

This research was supported by a grant from the Organic Research and Extension Initiative. of the United States Department of Agriculture.

Tags: agriculture, education, outreach, plants