New nanoparticle catalyst brings fuel-cell cars closer to showroom

A University of Wisconsin–Madison and University of Maryland (UM) team has developed a new nanotechnology-driven chemical catalyst that paves the way for more efficient hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles.

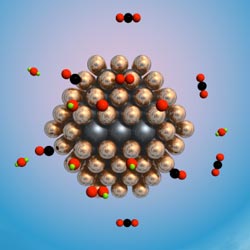

Writing in this week’s Advance Online Publication of Nature Materials, UW–Madison chemical and biological engineering Professor Manos Mavrikakis and UM chemistry and biochemistry Professor Bryan Eichhorn describe a new type of catalyst created by surrounding a nanoparticle of ruthenium (Ru) with one to two layers of platinum (Pt) atoms. The result is a robust room-temperature catalyst that dramatically improves a key hydrogen purification reaction and leaves more hydrogen available to make energy in the fuel cell.

UW–Madison and University of Maryland researchers developed a new type of catalyst by surrounding a nanoparticle of ruthenium with one to two layers of platinum atoms. The result is a robust room-temperature catalyst that dramatically improves a key hydrogen purification reaction and leaves more hydrogen available to make energy in the fuel cell.

One day, it could be common for fuel cells to create electricity by consuming hydrogen generated from renewable resources. For now, most of the world’s hydrogen supply is derived from fossil fuels in a process called reforming.

An important step in this multistage process, called preferential oxidation of CO in the presence of hydrogen (PROX), uses a catalyst to purge hydrogen of carbon monoxide (CO) before it enters the fuel cell. CO presents a major obstacle to the practical application of fuel cells because it poisons the expensive platinum catalyst that runs the fuel cell reaction.

Attractive for transportation applications and as a battery replacement, proton exchange membrane fuel cells generate electricity using porous carbon electrodes containing a platinum catalyst separated by a solid polymer. Hydrogen fuel enters one side of the cell and oxygen enters on the opposite side. Platinum facilitates the production of protons from molecular hydrogen, and these protons cross the membrane to react with oxygen on the other side. The result is electricity with water and heat as byproducts.

A conventionally constructed catalyst combining ruthenium and platinum must be heated to 70 degrees Celsius or 158 degrees Fahrenheit in order to drive the PROX reaction, but the same elements combined as core-shell nanoparticles operate at room temperature. The lower the temperature at which catalyst activates the reactants and makes the products, the more energy is saved.

"We understand why it works," Mavrikakis says. "We know now the reason behind this marvelous behavior. The first reason is the core-cell nanostructure. This polymer-based method developed by my colleagues in Maryland allows the exact amount of an element, in this case platinum, to be placed exactly where you want it to be on specific seeds of ruthenium."

This very specific nano-architecture and composition can sustain significantly less CO on its surface than pure Pt would. Because the binding is weaker, Mavrikakis says fewer sites on the core-cell nanostructure are available to bind with CO than would occur with Pt alone. That leaves empty sites for oxygen to come in and react.

"The second reason is that there is a completely new reaction mechanism that makes this work so well," he says. "We call it hydrogen-assisted CO oxidation. It uses atomic hydrogen to attack molecular oxygen and make a hydroperoxy intermediate, which in turn, easily produces atomic oxygen. Then, atomic oxygen selectively attacks CO to produce CO2, leaving much more molecular hydrogen free to be fed to the fuel cell than pure Pt does."

While the breakthrough is important to the development of fuel-cell technology, the researchers say it’s even more significant to catalysis in general.

First, the team, including graduate students Anand Nilekar of UW–Madison and Selim Alayoglu of Maryland, used theory rather than an experimental approach to zero in on ruthenium/platinum as the ideal core shell system.

Second, the nanoscale fabrication of ruthenium and platinum resulted in a different nano-architecture than when ruthenium and platinum are combined in bulk. For the field of catalysis, the pairing of these approaches could bridge the gap between surface science and catalysis opening new paths to novel and more energy-efficient materials discovery for a variety of industrially important chemical processes.

Tags: business, energy, engineering, research