175th Anniversary: UW research spans the globe

UW’s global efforts range from finding and identifying the remains of service people in France, left, to research at the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica.

At Alumni Park, University of Wisconsin–Madison students past, present and future stop to take pictures of the lines radiating from a Numen Lumen seal set into the sidewalk. One line notes the exact distance — 9,181 miles — from Madison to the South Pole, where UW keeps research staff.

UW–Madison researchers are at work on every continent, recording collisions between neutrinos in Antarctic ice more than 9,000 miles away, following the path of disease transmission such as Zika and Ebola in West Africa, recovering and identifying the bodies of missing U.S. military service members in France through the UW–Madison Missing in Action Recovery and Identification Project and following the monarch butterfly migration to and from Mexico via Journey North.

“Research unifies humanity on a global stage,” says Cynthia Czajkowski, interim vice chancellor for research. “Worldwide, we share many of the same big and complex issues such as global warming, food insecurity, disease and even questioning how life began on earth. Throughout UW–Madison’s 175-year history, we have leveraged UW’s reputation, expertise and relationships to enhance our global reach, and in doing so, improve the way people around the world live, work and play.”

The Wisconsin Idea has outgrown state borders and, as science has become more mobile, now stretches across the globe and even out of this world.

International research requires teamwork among campus scientists and students, along with multicultural partnerships. While working internationally, researchers must comply with other countries’ laws and international ethical standards, and they sometimes face natural disasters and disease outbreaks.

Despite the barriers, international research projects showcase world-class faculty and are a source of pride at UW–Madison. While what follows is by no means comprehensive, here’s a look at some of UW’s research efforts on each continent.

Africa

Parts of the Milky Way along with the Large and Small Magellan Clouds (at bottom) appear in the night sky above the Southern African Large Telescope. Photo: Jeff Miller

Eric Wilcots, dean of the College of Letters & Science and professor of astronomy, uses the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT), dubbed “Africa’s Giant Eye on the Universe,” to conduct his research. The telescope was constructed by an international consortium of universities, including UW, and provides access to the astronomically rich skies of the southern hemisphere.

“Here at UW, our work, discoveries and teaching are all grounded in the Wisconsin Idea. That philosophy keeps us connected not only to one another, to our students and to the people of Wisconsin, but also to our peers far beyond the borders of our state,” says Wilcots. “When I came to UW–Madison nearly 30 years ago, I was drawn by the university’s balanced commitment to both local and international engagement — sharing research and knowledge for the betterment of all. I couldn’t be prouder of the immense role L&S plays in the fulfillment of the Wisconsin Idea on a global scale.”

Meanwhile, in his study of human evolution, John Hawks, Vilas-Borghesi Distinguished Achievement Professor in the Department of Anthropology, has explored caves in South Africa to study fossils of Homo naledi, an ancient hominin species. His work seeks to uncover the evolutionary tipping points that led to the emergence of homo sapiens.

North America

World-class fire ecology stretches from UW–Madison all the way to Yellowstone National Park. Here, graduate student Arielle Link downloads sensor data onto her laptop while professor and ecologist Monica Turner stands in the background. Photo: Althea Dotzour

UW–Madison’s presence in North America extends far beyond Wisconsin. UW researchers are studying historic logging impacts to spotted owls in the Sierra Nevada national forests, documenting impacts to our landscapes from a changing climate at Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks and even sampling ancient poop at a prehistoric city near present-day St. Louis to show how climate change may have contributed to the decline of a pre-Columbian Native American city called Cahokia.

Grace Bulltail, a professor in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, serves on a commission focusing on addressing violent crime within Indian lands and against American Indians and Alaska Natives. A member of the Crow Tribe and a descendant of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara tribes of Fort Berthold, North Dakota, Bulltail has spent much of her career studying the impact of natural resource extraction on water quality and watershed management.

South America

UW researcher Karen Strier observes muriqui monkeys in a forest in southeastern Brazil near the city of Caratinga. Photo Credit: João Marcos Rosa

UW–Madison’s Global Health Institute runs the One Health Center-Colombia in Medellin, Colombia, in partnership with Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Abbott Laboratories and the Ministry of Science and Technology-Colombia. Through these partnerships, OHC-Colombia developed vaccines for neglected diseases including Zika, Chikungunya and yellow fever.

“When I began the journey as GHI’s director in 2022, I wanted to expand the Wisconsin Idea worldwide and utilize a One Health approach that leverages UW–Madison’s expertise across its diverse schools and colleges for improving health for all humans, animals and plants,” says Jorge Osorio, GHI director. “Our OHC Network exemplifies our dedication to innovative solutions and collaborative partnerships across academia, government, industry and NGOs. Through this network, GHI empowers UW students and researchers to navigate complex health challenges with a holistic perspective, transcending disciplinary and geographic boundaries.”

The Global Health Institute’s One Health Center Network offers a framework to move research out of the lab into real-world settings. There are currently three OHCs, in various stages around the world, all located in emerging and infectious disease “hot spots:” Colombia, Sierra Leone and India.

Another South American project has taken a UW–Madison researcher to Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. Professor of Anthropology Karen Strier studies a critically endangered monkey — the northern muriqui. The 40-year-long study is built on collaboration with Brazilian scientists and is providing management guidance to the Brazilian government and nonprofit organizations to help with conservation efforts.

Europe

On Aug. 4, 2018, UW–Madison student Samantha Zinnen (right) sifts through soil taken from a dig site in northern France during a World War II M.I.A. soldier recovery mission that was a joint effort between UW–Madison’s Missing in Action Recovery and Identification Project and the U.S. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. The work has resulted in the identification of Army Air Forces 2nd Lt. Walter B. Stone, 24, of Andalusia, Alabama. He was buried in his hometown on May 11, 2019. Photo: Bryce Richter

Members of UW–Madison’s Missing in Action Recovery and Identification Project have spent weeks excavating sites in France to recover the bodies of service members who had been missing in action, and to identify them.

UW experts in different fields search archives to find possible locations, send teams in to do field work and then do DNA analysis to try to identify the remains found.

“We learned so much over the course of two years,” said Charles Konsitzke, associate director of the UW Biotechnology Center and facilitator for the MIA Project in 2017. “We all feel that this is a worthy cause and that we have experience and expertise to do it well.”

UW researchers also do important work at the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland, the world’s largest, most powerful particle accelerator.

In 2012, Sau Lan Wu, former professor of physics at UW–Madison, and her Wisconsin group played a leading role in the discovery of the Higgs Boson, thought to explain the existence of mass, and The University of Wisconsin Center for High Throughput Computing has been the principal institution of the Open Science Grid project, a consortium of partners in the United States that supports the Large Hadron Collider, among myriad other research projects.

Antarctica

Researchers prepare equipment outside the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica.

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is the first detector of its kind, designed to observe the cosmos from deep within the South Pole ice. Approximately 350 people from 59 institutions in 14 countries comprise the IceCube Collaboration.

UW–Madison is the lead institution, responsible for the maintenance and operations of the detector. Encompassing a cubic kilometer of ice, IceCube searches for nearly massless subatomic particles called neutrinos, which provide information to probe the most violent astrophysical sources: events like exploding stars, gamma-ray bursts and more.

Over the past few months, a team of IceCube drill engineers have set the stage for improving IceCube’s sensitivity to low energies. The majority of the team’s engineers come from UW–Madison’s Physical Sciences Laboratory, where they fabricate equipment for delivery to the South Pole. Additional drill engineers hail from Sweden, New Zealand and, for the first time, Thailand.

The geography of Antarctica reflects UW–Madison’s scientific work on the continent with 37 features named for UW faculty and students. The university has been home to large number of students and scientists studying glaciers, ice sheets and their geological imprint. Thwaites Glacier, a part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, was posthumously named after professor emeritus Fredrik T. Thwaites (1883–1961). Other Antarctic features named after UW–Madison glaciologists include Black Glacier (after Professor Robert F. Black), as well as Mount Bentley and the Bentley Subglacial Trench, both named after professor Charles R. Bentley.

Asia

Nanjing University President Kuang Yaming shakes hands with Millie Shain, wife of Chancellor Irving Shain (right), during the 1979 visit of a delegation the chancellor led to China. Image courtesy of the Wisconsin China Initiative

UW–Madison has a long history of scholarship in China, reaching back more than 100 years to when UW became one of the top public university recipients of Chinese students enrolling in American universities.

Forty years ago, UW–Madison Chancellor Irving Shain was the among the first American university presidents to visit China after it re-opened to the outside. A partnership agreement signed with Nanjing University by Shain in 1979 set the foundation for many more years of research collaboration and student exchange. Collaborations included industry partnerships with Nestle to develop and run a dairy farming institute.

UW–Madison climatologist John Kutzbach was awarded China’s highest scientific honor for foreigners in recognition of 30 years of collaboration that has advanced both American and Chinese climate science. Kutzbach, emeritus professor of atmospheric, oceanic and environmental sciences and former director of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies Center for Climatic Research, used models of the Earth’s climate to better understand previous climates and more accurately predict future ones. Beyond China, Kutzbach turned to records in Africa, Europe, Australia and other locations to test his simulations.

Other UW research in Asia ranges from work by Professor Prashant Sharma and his lab in the Department of Integrative Biology in discovering seven new species of blind cave spiders in Israel, to anthropology professor Mark Kenoyer‘s work studying cultural traditions and protecting ancient cultures of South Asia.

Australia

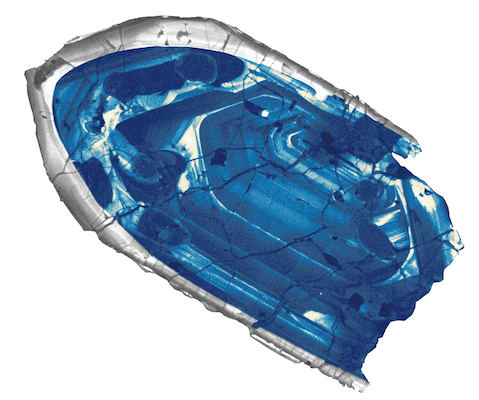

The oldest known piece of Earth’s crust — a 4.4 billion-year-old zircon crystal — viewed under a microscope.

“To geologists, rocks are books,” says John Valley, emeritus professor of geoscience.

Valley and his graduate students traveled to a sheep station in the Jack Hills of western Australia to check out rocks, with history-making results. In fact, they found the world’s oldest known rock to date — a 4.4-billion-year-old zircon aged just 160 million years younger than our solar system.

Valley’s journey to that discovery started with the help of his graduate student, William Peck (now chair of the Department of Geology at Colgate University). They were interested in analyzing the earliest oxygen-isotope ratios and targeting a mineral called zircon, which is the gold standard for determining the age of ancient rocks.

Another student, Aaron Cavosie, joined Valley when he returned to Australia in 2001. They collected about 1,000 pounds of rock and brought them back on the airplane. Shipping lots of rocks is complicated and can be pricey.

“We checked fourteen 70-pound suitcases and flew them back with us — it was cheaper and more reliable than any other way to ship them,” Valley recalls. “Today, the rules for transporting materials are a little different.”

In 2005, UW–Madison acquired its own ion microprobe, which has now been used by over 400 scientists from at least 20 countries. For the last three years, Valley has been collaborating with researchers in France and Germany conducting zircon research funded by a six-year Synergy Grant from the European Research Council.

“International research like this helps us to explore some of the biggest questions on the planet, such as when and where life began” Valley says.

Multinational

The rooftop of the Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences Building houses equipment for the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies. Credit: UW News

Some UW–Madison research projects have a presence at spots worldwide to collect data and compare local scenarios, notably research involving weather and studying carnivores.

To advance UW research in weather, the Space Science and Engineering Center was established in 1965, and the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies in 1976.

Data collected by satellites inform weather prediction models and allow meteorologists to more accurately forecast, saving lives and property.

“We need observations from all around the world,” says Bill Smith, the first head of CIMSS and a former senior scientist at UW. “The United States is joined in this research by Europe, China, Korea, Japan, India and others. University interactions with the rest of the world play a big role, not only in improving global weather prediction, but in education by bringing students from around the world to us, and by sending our students and scientists to other parts of the world to act as ambassadors.”

Paul Menzel, emeritus and former UW senior scientist at CIMSS, pursued research in remote sensing of atmospheric temperature and moisture. He was also one of the SSEC researchers to focus satellite eyes on Amazonia, to study the effects of rain forest burning on climate and ecology.

“It’s a long-held belief that the combination of satellite knowledge with local knowledge is the best way to forecast the weather wherever you are,” Menzel says. “Throughout our careers, we would go to another country to share what we knew, but we also learned so much from the people who hosted us. In the end, I think we gained much more than we delivered.”

For both Menzel and Smith, it is clear: UW cannot pursue the study of weather and climate today or into the future without international cooperation.

“SSEC was and continues to be a wonderful place to carry on the Wisconsin Idea — learn and share what you have learned with the world,” Menzel says. “You feel that when you are on the roof of the SSEC building on campus. You feel fortunate to be in Wisconsin, at the UW, and to have access to these rich data resources covering land, ocean and atmosphere that enable environmental research with national and international colleagues.”

Also leading research with a worldwide reach is Adrian Treves, professor of environmental studies at the Nelson Institute and director of the Carnivore Coexistence Lab since 2007. The CCL fosters research mentorships and projects spanning seven countries.

“We work in the United States and around the world because the problems people face with large carnivores are the same no matter where you look, with very few differences,” Treves says.

CCL projects include studying tigers in far east Russia, cheetahs in Kenya, lions and leopards in Rwanda, wolves in Europe, pumas and jaguars in Colombia, cougars and foxes in Chile as well as grizzlies, wolves and black bears in Canada. Treves explains that his students conduct research in other countries because not all conditions exist in the United States, though the problems are often the same.

Researchers and students have the chance to travel far and wide. PhD student Karann Putrevu headed to the far eastern regions of Russia to study the effects of Amur tigers on their prey. He’s also studied tigers’ conflicts with leopards in India and the political context of the South China tiger’s extinction in the wild. Drew Bantlin, another PhD candidate, worked in the Akagera National Park of Rwanda and surrounding villages studying how leopards, lions and spotted hyenas coexist with a rural population of small-holder crop and livestock growers.

“For students, the chance to conduct research abroad is a draw. Madison is a magnet for people interested in international ecology and those who view the role of the university as going way beyond the walls of campus and even the boundaries of the state,” Treves says.

Tags: UW175