Tomorrow’s Yellowstone

How a warming world is changing the places we love

Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, both part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, attract millions of visitors from across the globe each year, drawn there by the parks’ charismatic bison and majestic mountains, colorful hot springs and vast forests.

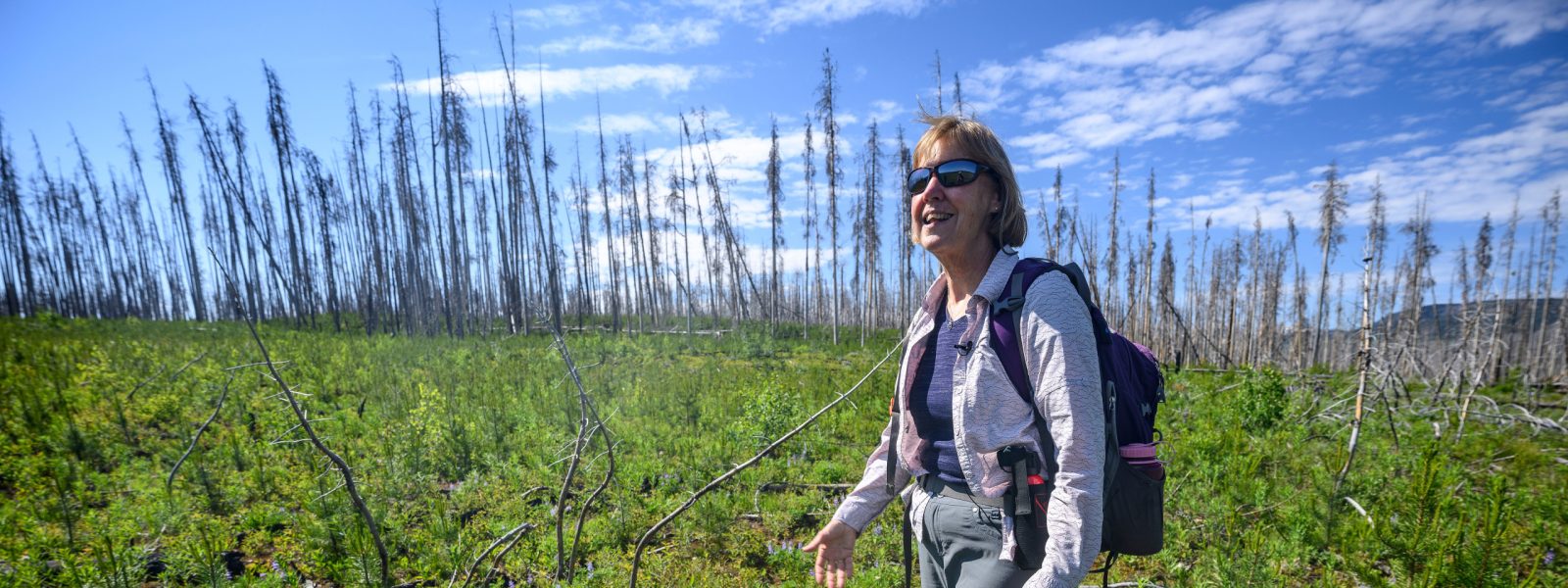

Monica Turner, a professor of integrative biology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, fell in love with the region in 1978 when she arrived at Yellowstone from the east coast of the U.S. as a 19-year-old interpretive ranger with the Student Conservation Association.

She was struck with awe at the immensity of the landscape and realized she wanted to better understand and sustain it. When she returned several years later, with a PhD and a commitment to study the region, the opportunity for a novel, long-term research project appeared: monitoring the landscapes’ recovery after the historic 1988 Yellowstone fires burned nearly one third of the park.

Today, Turner is a renowned landscape ecologist whose career has spanned more than 35 years studying the changes happening in the ecosystem’s forests.

And the forests are changing.

While no landscape is static, Turner, her students and colleagues have spent decades documenting shifts both subtle and significant, homing in on the effects of a climate changing due to human influence. Now, they’re using this wealth of data to predict the future, forecasting changes that may surprise the people who have come to love the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem of today.

The graphs and data points that create these computer-simulated forecasts may not be easy for most people to understand. But Turner and her team are finding ways to help reveal tomorrow’s Yellowstone in pictures based on the data. Using simulated images, they hope to show people landscapes that don’t yet exist, but might if the climate of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem continues to get warmer and drier.

Their models expect it will.

The shifts that result from a changing climate are often too subtle for any individual to see, and it can be difficult to fully understand their magnitude. But with recent road-buckling heat waves in the Pacific Northwest, glacial floods that wiped out towns in Pakistan and droughts threatening to dry out the Colorado River, Turner believes the public is starting to notice.

Even in Madison, Wisconsin, the summer of 2023 brought weeks of hazy skies and dangerous air quality as smoke from Canadian wildfires blanketed the city.

Yellowstone saw significant flooding in the summer of 2022 that wiped out roads, damaged wastewater infrastructure and led to the evacuation of visitors.

Change is coming to the places people love, and it’s getting harder to ignore.

Greater Yellowstone is just one ecosystem in one corner of the world. However, studying how one landscape responds as the climate heats up can help us understand what may happen in places around the world facing similar changes.

And since so many people love Yellowstone, it’s a great place to help the public appreciate the magnitude and tempo of climate change.

Yellowstone National Park forms the core of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, one of the largest nearly intact ecosystems in Earth’s temperate zone. The neighboring Grand Teton National Park and several national forests and wildlife refuges in the area comprise part of the larger ecosystem. Turner and her lab have field sites all over the region.

Because of her studies, Turner and her colleagues can see that the forests of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are changing. This is due, in large part, to changes in fire.

Fire has long been a natural part of the ecosystem.

Lodgepole pines are one of the most common tree species in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and they’re well adapted to the historical cadence of fires in the area, which researchers call the historic fire regime. In fact, once the trees are old enough, they produce cones that are designed to open in fire, helping the trees establish new stands.

But a warmer, drier climate is increasing the frequency of fires and disrupting the forests’ ability to recover as trees can no longer effectively disperse their seeds. Over time, the result will be patchier forests and fewer of the trees visitors are used to seeing in these iconic landscapes.

That’s concerning because forests are the backbone of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

“Yellowstone will change, and it’s changing at a faster rate than perhaps we had anticipated,” Turner says. “The vast forests that we see throughout the landscape from all those scenic vistas, many of those may disappear.”

A change in habitat also means a change in the resources that animals big and small rely on — animals visitors love to see.

Turner feels the urgency to find answers. That’s because what’s happening at Yellowstone foreshadows the subtle changes happening in other ecosystems around the world. Turner wants to help people grasp what’s coming; She may be uniquely poised to do so.

One of Turner’s biggest beacons of hope is the inspiration and ingenuity she sees in young people.

“I love the enthusiasm, the energy, the inquisitiveness and perseverance that the young scientists bring to our efforts,” Turner says. “I really enjoy the interchange with them and just the intellectual excitement that we get from that.”

Over the course of her career, Turner has brought more than 100 undergraduates to help with field research in Yellowstone, most of whom are from UW–Madison. Each field season is different, depending on her graduate students’ individual research projects, but they always update data and log observations for the lab’s long-term studies.

This summer, Timon Keller and Arielle Link, PhD students in the Turner lab, and Lucy McGuire, the lab’s manager, joined Turner in Yellowstone. They helped visitors see the changes that could happen to the landscape and surveyed their thoughts on climate change. They measured nitrogen levels and observed fungal relationships in the soil at past burn sites. And throughout the process, Turner helped the students ask and find answers to their own scientific questions. She also continues to help them think about how to share their results with the public.

Click below to meet some of the UW–Madison researchers at Yellowstone

Science doesn’t always happen in a lab. For Turner and her team, much of the science they do comes from time spent in the field, studying the landscape’s ecology and sharing their work with the people affected by climate change. That means everyone.

At their core, Turner and her students love the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and they want science to help sustain it so future generations can enjoy the unique forests and landscapes, too.

“Having this [experience] as an undergrad, I’m incredibly grateful,” says McGuire, who recently graduated and became manager of Turner’s lab. “Sometimes I can’t believe I’m doing it. We’re driving around, and I’m just like ‘Wow, this is where I’m working.’”

While their field season is busy with data collection and hands-on training in the field, the team also finds time to recharge in the same natural beauty that draws park visitors to Yellowstone every day.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is a place people have loved since long before it was designated national park land. There are 27 tribes with ties to the land and its resources, and Indigenous people have inhabited the region since time immemorial. Studying the landscape and including more perspectives on sustaining them is vital to ensuring people from all backgrounds can visit, learn, connect with the place and be inspired by it for many years to come. While tomorrow’s Yellowstone will look different than today’s, the magnitude of that difference depends on the actions of all of us.

Explore these other stories to learn more about the team, the science behind their work and the changes the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem could face in the next century.