Gamer-Teacher collaboration yields nine middle school science games

Nine educational video games developed in an unusual collaboration between middle school science teachers and expert game developers have been released nationally by Field Day lab, a project of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Wisconsin Institute for Discovery.

The games cover earthquakes, the carbon cycle and the water cycle, among other topics chosen by the teachers during a January workshop on campus.

“The main thing we learned was that this collaboration with teachers was even possible,” says David Gagnon, director of Field Day. “There are so many barriers in the world of educational games. There is really great theory and fantastic scholarship out of UW–Madison and elsewhere, but in general, the adoption in schools is a bit lackluster, and games don’t yet fit as well as they deserve to.”

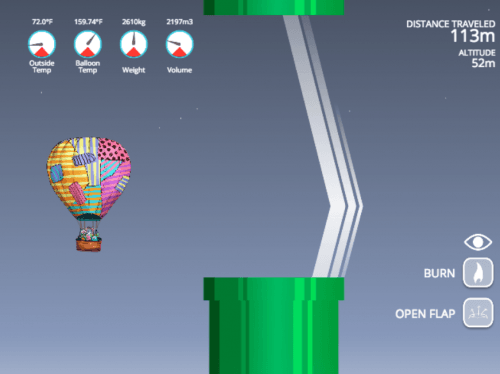

A game based on hot air balloons teaches basic principles on the physics of gases. Field Day

With teachers present at the creation, he says, “We were able to build games that were designed, first and foremost, from the teacher perspective, and we came out with products that will be easier to integrate into middle schools.

“Middle schools are a decisive moment in identity formation of youth,” Gagnon says, since games blend learning through exploration with learning by doing. Gamers who “fail in playful ways” can be encouraged to try again, he adds.

Instead of focusing on facts, the games focus on systems, which are the bedrock of science, Gagnon says. “Games help respond to a tension that exists in education, to teach a lot of content without a lot of depth.”

In the next school year, Field Day will enter the realm of history, as Field Day is recruiting a new crop of 18 teachers. “We plan to have kids develop history games,” Gagnon says. “Instead of a research essay as the final project, they will make a researched game. We think this will deepen their understanding of history.”

Since the January workshop that brought seven science teachers from around Wisconsin to the Field Day lab, “the teachers have been working with us to improve the games and test each version with their kids,” Gagnon says. “We need to be sure they are feasible to use in school, and that they are effective teaching tools. Having teachers as co-designers gave us a window into their experience, and we benefitted from wisdom that they could not necessarily verbalize.”

During the most intense period of development this winter and spring, “we were play testing Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and creating new versions of the games in between. We did that for months; the pace was nutty.”

“If kids can see that science is actually about experimentation, not about memorizing facts, this will increase the number of good scientists a generation later,”

David Gagnon

One challenge in development was to limit “scope creep,” Gagnon says. “Each game wants to become a million-dollar project, but you can see that these are very small; there was a tiny educational bulls-eye we wanted to hit.”

The project was supported by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and the Wisconsin Digital Learning Collaborative.

The games will be formally introduced at the annual conference this week of the Games+Learning+Society program at UW–Madison, which was started by noted video-game educators Kurt Squire and Constance Steinkuhler. Although they recently announced their impending departure to the University of California, Gagnon, who studied under Squire, says “When Kurt and Constance came, educational games were not an accepted thing. After years of scholarship and data, they succeeded in creating a community of scholars, designers, policy makers, and spinoffs like Filament Games that acknowledge the value of games. There is enough infrastructure in place that while their departure is a catastrophe, the impact of their work will remain.”

Games are a process of learning from trial and error, Gagnon says. In science, that’s called experimentation. “If kids can see that science is actually about experimentation, not about memorizing facts, this will increase the number of good scientists a generation later,” Gagnon says.