UW-Madison spinoff releases latest educational game – aimed at fractions

Art Director Alexander Cooney creates environments for an upcoming Filament game. David Tenenbaum

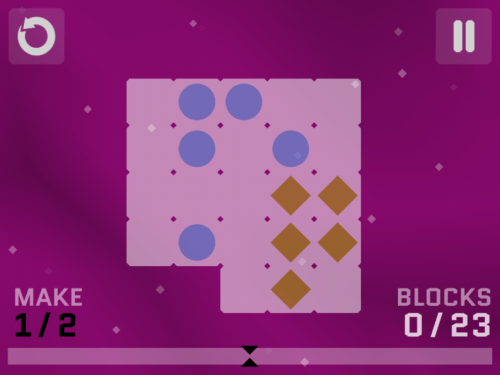

A Madison maker of educational games has just published Diffission, a visual game to teach fractions to middle schoolers without the pain of the traditional “skill and drill.”

The software will generate up to one billion shapes, and users will have to build fractions from them, says Filament Games CEO Dan White. “It’s very tactile, and imparts a conceptual understanding of fractions that’s very difficult to convey using traditional numerical methods.”

Diffission joins 13 other games in Filament’s “library.” The company sells individual games on the web, but its marketing strategy focuses on licensing the library of games to schools or school districts.

In August 2015, the Sun Prairie school district bought a district-wide license for all students.

White and co-founders Alex Stone and Daniel Norton were already experienced gamers in 2007, when they began work on an ocean science game at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

A screenshot from Diffission, a new game from Filament Games in Madison, asks players to create the fraction 1/2 from the on-screen elements. Image: Filament Games

“The player took on the role of a researcher on an alien planet, trying to understand the ecosystem,” White says. “We presented the game at a conference, and a member of the audience from the Marion Ewing Kauffman Foundation approached us about plans to build a curriculum on ocean science.”

Kauffman’s $1 million grant “allowed us to hire our first staff and figure out how to be a real company,” White says. Filament now has 40 full-time employees and offices on West Washington Ave. in Madison.

The game, called Resilient Planet, “allows you to dive into a world that you know nothing about,” White says. “You get to explore, to engage in inquiry and see what happens. The students drive the experience and own the outcome.”

Filament has three business lines: developing and publishing its own games, distributing games made by others, and doing contract work for companies or organizations.

One of Filament’s steadiest clients is iCivics, an organization founded by Sandra Day O’Connor after she retired from the Supreme Court. The series of 21 iCivics games, “is used in 50 states by 80,000 to 90,000 registered teachers and has been played at least 33 million times.”

Using the games, “students learn through experimentation and low stakes failure, and dare I say even enjoy themselves in the process,” White says.

Filament emerged with UW–Madison’s games-for-learning research program that’s now called Games+Learning+Society, says the program’s director, Kurt Squire. “Filament was our first ‘in house’ development team, when we were housed at UW-System’s Academic ADL Co-Lab, and Dan White graduated from our program.”

“Games are valuable because they map well to modern theories of learning. They immerse players in problem-solving experiences in which they can learn in the context of doing.”

Kurt Squire

Squire and Constance Steinkuehler, co-director of Games+Learning+Society, will be leaving UW–Madison for the University of California at the end of this year.

Many of Filament’s employees were educated at UW–Madison and UW-Whitewater. White has a master’s in curriculum and instruction from UW–Madison, while Stone has a BS in computer science. Norton is creative director.

White describes the job of educational game designer as serving as “the conduit between the subject-matter expert and the player. Often, the less the designer knows about the subject at the outset, the better, because they learn how to teach it in the process of teaching themselves.”

Some subjects are more conducive to game play than others, White says. Science, with its systems, including the solar system and the ocean ecosystem, are typically good subjects. Less suitable material includes “flat content like multiplication tables. We can make candy-coated flash cards, but that’s a nuclear powered flyswatter; paper flash cards work fine,” White says.

Marketing a technology associated with fun to the serious business of education can be challenging, White agrees, but once adoption begins, teacher anecdotes are encouraging, especially concerning hard-to-reach students.

“It’s not uncommon for teachers to remark with astonishment at the degree to which good learning games can transform disengaged students into motivated students who collaborate with their peers, talk about the material after class or do research of their own volition,” White says.

“Games are valuable because they map well to modern theories of learning,” says Squire. “They immerse players in problem-solving experiences in which they can learn in the context of doing.”

As games gain a foothold in schools, Squire adds, “the real challenge is creating good ones that are well integrated with curricula and help improve instruction by providing teachers, students and parents better data about learning. Filament is absolutely at the forefront in all of these areas, and is a real credit to the university, region and community.”

White forecasts the increasing acceptance of games. “In the beginning, we spent a lot of breath talking about why game-based learning is a good idea. We don’t have to do that so much anymore.”