Greenhouses contend with the climate to keep plants growing

With outside temperatures close to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, Botany Department horticulturalist Cara Streekstra waters plants in the Botany Greenhouse during the stifling summer of 2012. Photo: Bryce Richter

Lynn Hummel pays attention to the weather. Especially when it’s time to spray for insects.

“Imagine getting into a protective suit, you can’t breathe in there, and it’s 93 degrees out and humid. It just exacerbates everything,” says Hummel, manager of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Walnut Street Greenhouse. “And your discomfort level is through the roof. So you can’t wait to get out of the thing. Sometimes you have be in there for two, three hours.”

So he noticed when, after the intense heat of 2012, the last few summers have been milder. The weather controls a lot about his job running the large complex on the west side of campus that grows plants for research projects. To control the climate inside the greenhouses, Hummel has to contend with the climate just outside.

Rice and Coleus plants thrive in the misted, 86-degree warmth of the research house at the Botany Greenhouse in January 2008. Photo: Jeff Miller

Many greenhouses are spread across more than a mile on campus — and even several miles off it: Botany, D.C. Smith, Walnut Street, West Madison, King Hall, the Biotron. Even a residence hall (the one named after Aldo Leopold) boasts one on its roof as part of the residential learning community called, fittingly, GreenHouse.

These structures provide study material for botany and horticulture courses and the precisely controlled climates required for experiments. And UW–Madison plant breeders rely on greenhouses to improve crop varieties more quickly, eking out a second growing season in the middle of the Wisconsin winter.

Managing these greenhouses is a full-time job. Several, in fact. Aging structures, changing research and finicky plants provide plenty of work for the dedicated greenhouse staff. Even the changing climate can affect greenhouses built for a Wisconsin climate now a century out of date.

Succulent plants fill the desert house at the Botany Greenhouse in January 2008. Photo: Jeff Miller

The Botany Greenhouse at Birge Hall was built as part of the then-new biology building in 1912 and was expanded in the 1950s to a total of more than 8,000 square feet. The decision to place the greenhouse right up against the existing building would haunt future directors.

“When they started, they were just planning to grow plants for teaching,” says Mo Fayyaz, who directed the Botany Garden and Greenhouse for 33 years before retiring last August.

In the decades since, botanical research has demanded increasingly controlled conditions. At the same time, the collection has expanded to include plants from all over the world. Climate control is more crucial than ever.

Ingrid Jordon-Thaden took over as the Director of Botany Garden and Greenhouse last year. The century-old decision to join the greenhouses to the rest of the building limits her ability to cool them off in the summer, because it restricts airflow — the biggest help in keeping temperatures down.

“In the summer when it gets really hot, some of our fragile plants die. In our first heat wave in May, we lost a handful of important plants,” says Jordon-Thaden, who came to UW–Madison from the University of California, Berkeley. “So in the fall, we’re spending a lot of time recovering from the summer, rejuvenating them, bringing them back from stress.”

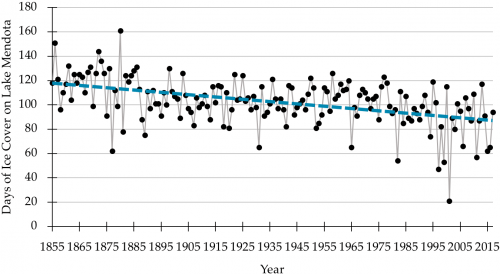

The annual duration of ice cover on Lake Mendota going back to 1855 shows an average decrease of about two days of ice cover per decade, as shown by the blue line. Eric Hamilton/Wisconsin State Climatology Office

Wisconsin’s climate has fluctuated over the decades, with warmer and cooler periods. By one metric — the duration of ice cover on Lake Mendota — Madison’s climate has trended warmer since 1855, when records began. Mendota’s ice cover has shrunk by an average of two days a decade, shaving off 20 days since 1912. As the global climate warms, Jordon-Thaden is expecting hotter, longer and muggier summers.

So with funds from the UW–Madison College of Letters & Science, Jordon-Thaden has installed new, cooling shade cloth to the greenhouses and started keeping temperature records. She is also fundraising to add air conditioning, but the greenhouse must wait for utility upgrades to the 116-year-old building to provide the capacity for better cooling systems.

New shade cloth will help keep the Botany Greenhouse cooler in the summer. Photo: Ingrid Jordon-Thaden

“We have some very special plants that are given to us from other collections from all over the world from a wide variety of climates,” Jordon-Thaden says. “So, our climate control system really needs to be able to accommodate this plant diversity, making the need for improvements even more pressing.”

Related: Q&A with Ingrid Jordon-Thaden

That diverse collection supports studies of plant diversity and evolution. The greenhouse also grows plants to populate the Botany Garden, directly outside of the greenhouses attached to Birge Hall, which organizes plants by their family relationships.

A mile west of Birge Hall, Hummel has an array of tools at his disposal to keep the Walnut Street Greenhouses cool, warm or anything in between.

Graduate students Courtney Glettner, left, and Rachel Bouressa record weekly measurements in the Walnut Street Greenhouse in May 2013. Photo: Jeff Miller

“It’s a state-of-the-art greenhouse. You’ll struggle to find better than this,” Hummel says as he walks through an addition built in 2005. In total, Walnut Street provides 15,000 square feet of bench space for research.

Many of the controls are automated. High-powered lights provide plenty of light, and switch off and on in response to the sun. Shade cloth, ceiling ridge vents, powerful fans and air conditioning provide multiple lines of defense against the hot summer sun. The openness of the design gives Hummel the airflow he needs.

And then there’s the Lord and Burnham greenhouses.

“Lord and Burnham was the Cadillac of greenhouses, and UW bought those,” says Hummel of the older section of greenhouses at Walnut Street. “They probably were wonderful for their day, but in this day and age they’re just outdated.”

Student members of the aptly named GreenHouse Learning Community gather in the greenhouse atop Leopold Residence Hall in 2013. Photo: Bryce Richter

Built in the 1950s, these houses are slated to be removed when new modules are added. Manual side vents make the airflow hard to control, letting the temperatures spike to 130 degrees some days. Beet breeder Irwin Goldman, a professor of horticulture, has moved out of one for the summer field season, but he’ll be back in the fall to keep his beet program moving quickly.

Hummel has also noticed changes in the climate during his 25-year tenure.

“It just seems like we have these great falls now go on, and the garden has vegetables until mid-October without any problem. And then the springs have seemed cooler,” he says.

As long as the climate keeps shifting and research needs change, greenhouse leaders like Hummel and Jordon-Thaden will find a way to battle weather and pests to keep the plants in their charge thriving.

Tags: botany, horticulture, learning, research