UW scientists find key cues to regulate bone-building cells

The prospect of regenerating bone lost to cancer or trauma is a step closer to the clinic as University of Wisconsin–Madison scientists have identified two proteins found in bone marrow as key regulators of the master cells responsible for making new bone.

In a study published online Feb. 2 in the journal Stem Cell Reports, a team of UW–Madison scientists reports that the proteins govern the activity of mesenchymal stem cells — precursor cells found in marrow that make bone and cartilage. The discovery opens the door to devising implants seeded with cells that can replace bone tissue lost to disease or injury.

“These are pretty interesting molecules,” explains Wan-Ju Li, a UW–Madison professor of orthopedics and biomedical engineering, of the bone marrow proteins lipocalin-2 and prolactin. “We found that they are critical in regulating the fate of mesenchymal stem cells.”

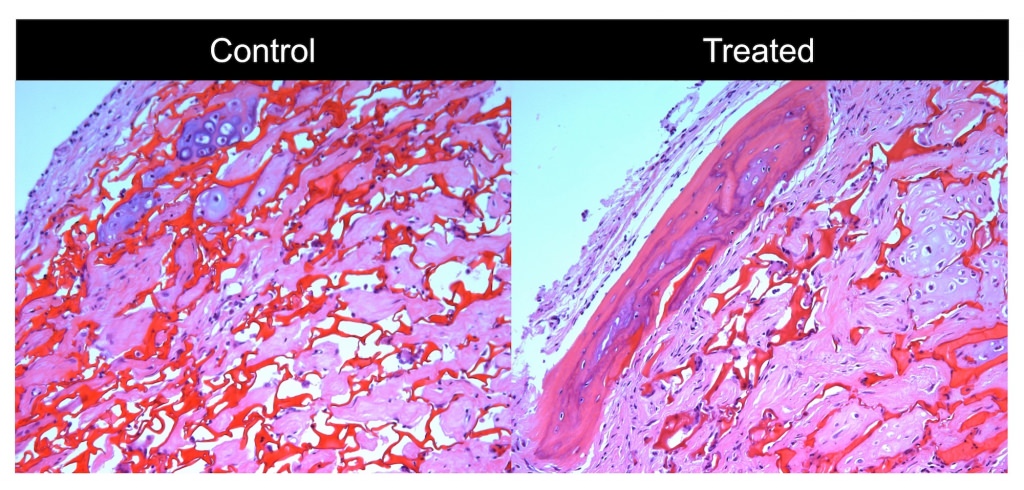

Micrographs show the difference between treated and untreated bone cells in a mouse model of severe bone loss. Wisconsin researchers have identified two native protein factors that help keep mesenchymal stem cells — the master cells that make bone and cartilage — happy in the laboratory dish. The work could one day help make regenerating lost bone in patients a reality. Photo: Wan-Ju Li

Li and Tsung-Lin Tsai, a UW–Madison postdoctoral researcher, scoured donated human bone marrow using high-throughput protein arrays to identify proteins of interest and then determined the activity of mesenchymal stem cells exposed to the proteins in culture. A goal of the study, says Li, is to better understand the bone marrow niche where mesenchymal stem cells reside in the body so that researchers can improve culture conditions for growing the cells in the lab and for therapy.

The Wisconsin researchers found that exposing mesenchymal stem cells to a combination of lipocalin-2 and prolactin in culture reduces and slows senescence, the natural process that robs cells of their power to divide and grow. Li says keeping the cells happy and primed outside the body, but reining in their power to grow and make bone tissue until after they are implanted in a patient, is key.

The ability to precisely manipulate mesenchymal stem cells in the laboratory dish and keep them poised to divide and form bone on cue helps pave the way for using cell-bearing three-dimensional matrices to reconstruct large swaths of bone lost to tumors or major trauma. Because bone has some natural healing properties, things like breaks and fractures can often mend themselves. But when large pieces of bone are lost, clinical intervention is required.

“We’re seeking better treatments for bone repair,” says Li, who is affiliated with the UW School of Medicine and Public Health.

To engineer the growth of new bone in the body through regenerative medicine first requires generating large amounts of good quality cells in the lab, notes Li. In the body stem cells are rare. But if cell growth, differentiation and quality can be controlled in the lab dish, it may be possible to create stocks of cells for therapeutic applications and prime them for bone regeneration once implanted in a patient.

The Wisconsin team successfully tested human cells treated with lipocalin-2 and prolactin to regrow bone by implanting them in mice with a calvarial defect, where part of the skullcap has been surgically removed to model critical-sized bone loss.

The discovery opens the door to devising implants seeded with cells that can replace bone tissue lost to disease or injury.

The human marrow used in the new Wisconsin study was donated by patients undergoing hip replacement surgery. Thus, a caveat to the study is that the protein factors identified by Li and his colleague came from donors with osteoarthritis. However, Li expressed confidence that the factors from the marrow used in the study would be similar or identical to what occurs in a healthy patient.

The new study, says Li, demonstrates a key improvement to the lab culture environment, which seeks to mimic the bone marrow niche where mesenchymal stem cells are found in the body.

The Wisconsin research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AR064803.