UW–Madison researchers begin work on Zika virus

In October, when David O’Connor last visited Brazil as part of a decade-long research program studying drug-resistant strains of HIV, one of his Brazilian collaborators had a request.

“He asked about using some of the technologies we have developed to look for new viruses to study some unusual cases of a birth defect, microcephaly, in the north of Brazil,” says O’Connor, a University of Wisconsin–Madison pathology professor.

The babies born with underdeveloped brains and small heads were the relatively quiet beginning of worry over the spread of Zika virus, concern that has grown louder outside Brazil with an international outbreak and emergency attention from public health officials around the world.

“At the time we didn’t know it would explode into the public consciousness like it did,” O’Connor says. “But we did start planning.”

That planning will soon culminate in some of the first experiments studying Zika virus in monkeys, conducted by a broad UW–Madison team that includes the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center and expertise in infectious disease, pregnancy and neurology.

Pathobiological sciences Professor Jorge Osorio and research scientist Matthew Aliota, who were first to identify the Zika virus circulating in Colombia in October, provided essential Zika virology expertise. Ted Golos, professor of obstetrics and comparative biosciences, studies how other infections during pregnancy impact newborn health. The research group has extensive experience with viruses in humans and nonhuman primates — such as HIV and influenza — and their work will be conducted in secure facilities designed for the safe study of potentially harmful viruses.

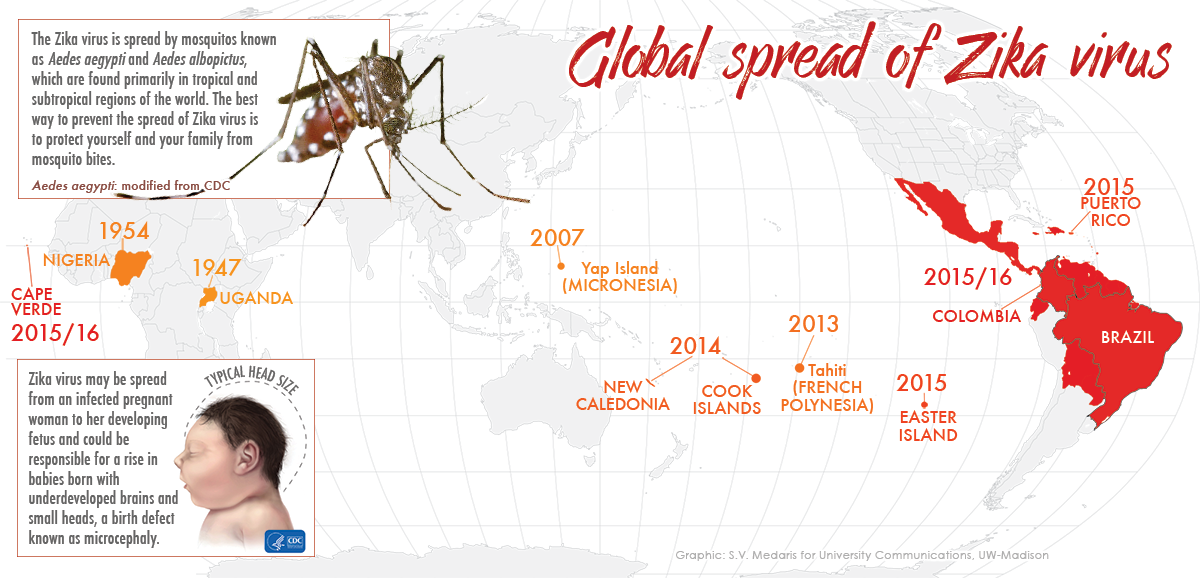

Zika virus is transmitted by a specific mosquito called Aedes aegypti. Photo: James Gathany/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

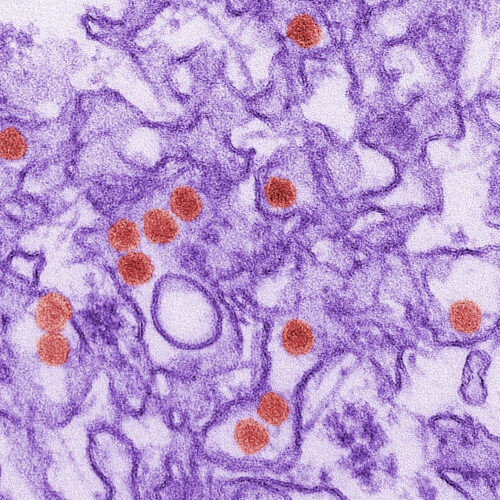

Their work will start with basic questions about Zika virus infection. Very little is known about the virus even though more than 50 years have passed since it was discovered in the Zika Forest in Uganda.

Until recently, Zika was expected to cause little more than flu-like symptoms — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists fever, joint pain and a headache — in about 20 percent of the people it infected.

“That’s why it’s an understudied virus,” O’Connor says. “The viruses that get the most attention are the ones that makes us the most sick.”

The rapid spread of the virus and potential connection to an otherwise rare birth defect have drawn plenty of attention from the public and from government officials.

“People want clear answers, and we want to be able to make clear public health recommendations,” says Thomas Friedrich, a UW–Madison professor of pathobiological sciences. “There are a lot of countries in the tropics right now saying, ‘Don’t get pregnant until 2018.’ That’s not a sustainable public health recommendation.”

This is a digitally-colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of Zika virus. Virus particles are colored red. Image: Cynthia Goldsmith/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In January, the National Institutes of Health made Zika virus research a high priority, and the groundwork underway at UW–Madison led to NIH support for a series of studies of the virus in macaques, monkeys whose physiology and immune systems are similar to humans.

The researchers will track the effects of initial infections, but also try to establish whether one Zika virus infection provides some protection against future infection — like chicken pox does.

Zika does not mutate particularly fast, the feature of HIV and influenza that makes those viruses hard to pin down with vaccines (like HIV) and leaves people open to reinfection seasonally (like flu). This may make Zika easier to head off with a vaccine, but the best sort of immune response to provoke with a vaccine is not yet known.

“That’s why we need to have data that shows what natural immunity looks like and the sort of immune responses that arise to protect an individual when they encounter that virus again,” O’Connor says.

Perhaps more hotly anticipated will be results from planned studies of Zika and pregnancy.

“We strongly suspect Zika infection during pregnancy is associated with birth defects such as microcephaly,” Friedrich says. “But we don’t know how strong the link is, or what percentage of women who get infected might give birth to children with birth defects.”

“The key messages are that we don’t know a lot. We will know a lot 12 months from now. But it’s really important we let data guide the decision making, not our guts.”

David O’Connor

Or whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy matters. Or whether it is direct infection of a developing fetus by the virus or the immune response the infection sparks in pregnant women that causes problems like microcephaly.

“There are questions that cannot be safely and ethically addressed in humans that are absolutely vital,” O’Connor says. “What we will learn about Zika from the monkeys will hopefully have an immediate application when figuring out how to deal with this from a public health perspective.”

Working with the Zika virus from the original 1947 discovery in Africa and from the ongoing South American outbreak — provided by UW–Madison Osorio and Aliota, who were first to identify Zika virus circulating in Colombia in October — the researchers also hope to identify any important differences in infection by the different strains.

O’Connor also hopes results from the studies will help settle minds around the world, and help change the tenor of Zika news stories.

“The more hyperbolic the media coverage is, the more it gets repeated, reposted, retweeted,” he says. “The key messages are that we don’t know a lot. We will know a lot 12 months from now. But it’s really important we let data guide the decision making, not our guts.”