No evidence of COVID-19 spread to local community after UW–Madison residence hall outbreak

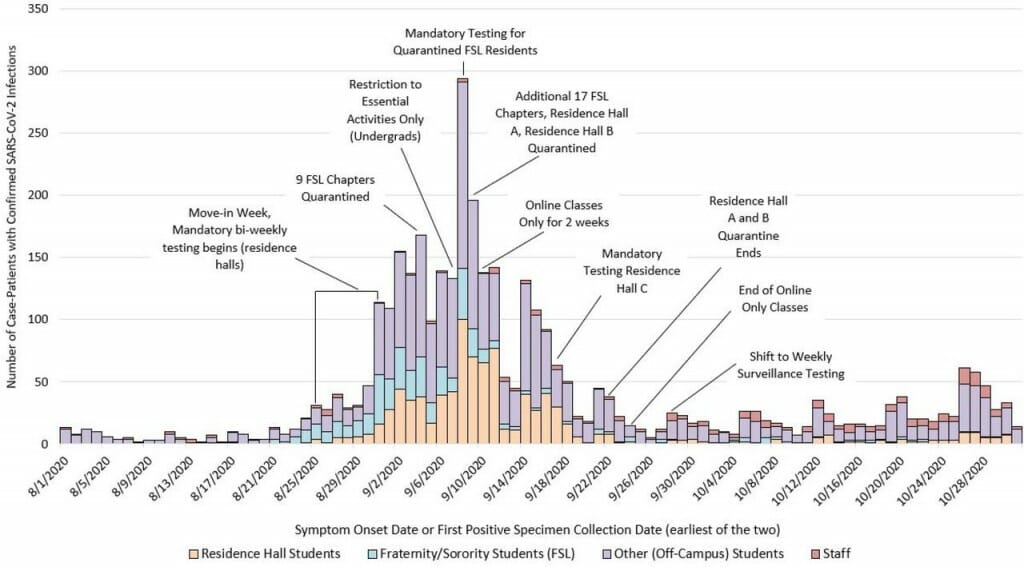

The epidemic curve of COVID-19 cases among UW–Madison students and employees between Aug. 1 and Oct. 31, 2020. The figure, from a study led by the CDC, describes the interventions undertaken by campus and Public Health Madison and Dane County in light of a rapid increase in cases at the start of the fall semester. The study shows the interventions, such as quarantine, likely helped contain the outbreak. Between Aug 25 and Oct 31, residence halls A and B accounted for 68.5% of all residence hall cases but only 34.4% of all students living in residence halls. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study

A study led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s prevention efforts likely helped contain an outbreak of COVID-19 in two large residence halls in the fall of 2020. The outbreak, marked by a high number of cases among undergraduate student residents as the semester began, did not appear to result in widespread community transmission.

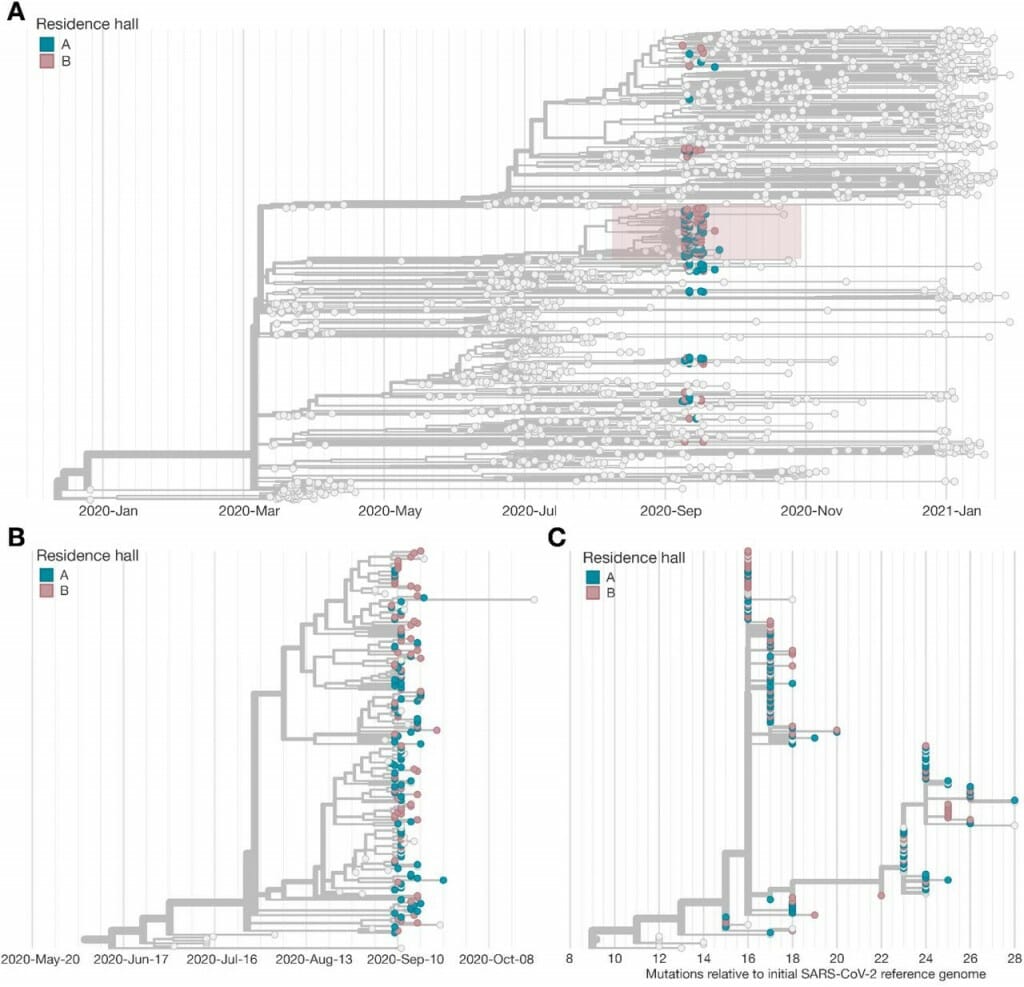

The study, which was published ahead of peer review on the preprint server medRxiv, combined epidemiologic data with whole genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 samples taken from COVID-19-positive students living in Witte and Sellery residence halls throughout the outbreak period, which spanned Sept. 8-through-22, 2020. (CDC did not identify the residence halls by name in the study.)

During that period, students in the two residence halls were quarantined for two weeks, all in-person classes and social activities on the UW–Madison campus were cancelled, and the university hosted mass COVID-19 testing and implemented frequent testing in other residence halls. Additionally, Public Health Madison and Dane County — which has jurisdiction over student housing off-campus — mandated testing and quarantine for 26 fraternity and sorority houses.

The fall outbreak informed the spring campus response to COVID-19, the study authors note. UW–Madison increased frequency of testing to twice per week for students living on campus and living off-campus. A student fills a vial containing a COVID-19 saliva test sample at a testing location at the Pyle Center on Jan. 14. Photo: Bryce Richter

Student data from Witte and Sellery were compared to the whole genome sequences of virus samples collected from 875 patients of University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics between Sept. 1, 2020 and Jan. 31, 2021. The community samples represented 3 percent of the positive COVID-19 cases in Dane County for that time period.

“If there had been substantial transmission coming from those two dorms due to spillover into the community, that likely would have been detected within that 3 percent community whole genome sequencing sample,” says Dustin Currie, lead author of the study and a CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer. “It’s hard to point to a specific intervention and say what may have reduced the transmission on campus, but the series of interventions put in place as the outbreak was detected, including the quarantine of those two residence halls, additional testing, and suspension of in-person classes and activities, was followed by a pretty substantial decrease in transmission to baseline levels.”

Whole genome sequencing is, explains study co-author and UW–Madison cellular and molecular pathology graduate student Gage Moreno, like looking at the fingerprint of the virus affecting each person. The SARS-CoV-2 virus accumulates small changes, or mutations, roughly every other time it transmits from one person to another, leaving genetic fingerprints that researchers like Moreno can track.

“You can use those fingerprints to really track down where (the individual virus) came from, and where it’s going and how long it’s circulated there,” Moreno explains.

Students visit a COVID-19 testing site on Henry Mall on Sept. 2. At the start of the fall semester, residence hall students were required to test once every two weeks, or more frequently if they experienced symptoms. During the outbreak, the university increased testing frequency. Photo: Bryce Richter

Scientists at the AIDS Vaccine Research Laboratory, where Moreno is based, had already been examining the genetic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 on campus through a separate project funded by the CDC and led by Professor Thomas Friedrich and Professor David O’Connor. In fact, the lab sequences about 5 percent of the virus samples in the county, making Dane County one of the leading places in the U.S. where this kind of viral surveillance is performed.

When the outbreak happened, Moreno says, “we were really concerned that, with this high amount of transmission, are those sequences going to spillover into our community? Is that going to make our community outbreak worse?”

Between Aug. 1 and Oct. 31, 245 in-person and remote employees and 3,485 UW–Madison students living both on and off campus tested positive for COVID-19. With the assistance of interim Medical Director of University Health Services Patrick Kelly, Moreno obtained and sequenced 262 positive nasal swab samples collected for PCR testing from Witte and Sellery Hall residents between Sept. 8 and Sept. 22.

“One of the key pieces that makes this different from a lot of other studies is this is a population where all of the tests were PCR,” says Kelly. Nearly all COVID-19 testing on the UW–Madison campus has been by PCR, considered the gold standard for detecting the virus.

Two-thirds of the viruses from the students had a unique mutation not seen in Dane County prior to the outbreak, while the remaining student sequences were closely related to viral lineages already circulating in the community. Most of the new circulating viruses in Dane County after the outbreak were not affiliated with viruses circulating in Witte and Sellery, the researchers say.

“We kept that going for the entire duration of the semester and we really did not see those viruses,” says Moreno.

Adds Currie: “If they were widely circulating in the community, at that point, we would expect that some of the sequences in the community would have had those lineages.”

Moreno suggests that things could have gone differently, given that 20 percent of cases typically give rise to 80 percent of downstream infections.

“I think I really expected there just to be continued transmission of these variants, because that’s kind of what we’ve all been trained to expect in this pandemic,” Moreno says. “But it was a really pleasant surprise to see that the quarantining of the dorms worked…there was obviously a massive fire in the dorms and the quarantine was like the extinguisher around the edges.”

The study also found that more than eight in 10 students and employees who tested positive for COVID-19 between Aug. 1 and Oct. 31 experienced symptoms, and the most common were headache, sore throat and fatigue. Most met the clinical criteria for COVID-19 by experiencing at least one major symptom, such as loss of smell, or a combination of symptoms like fever with headache.

Additionally, residence hall students with roommates were more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than those who lived alone, and genetic overlap between their viral fingerprints suggests that one roommate passed the virus to the other, or both were exposed to a common source.

Currie says whole genome sequencing also showed a lot of viral mixing between Witte and Sellery, suggesting transmission may have taken place in social settings where residents of both were spending time: “These weren’t two separate outbreaks that formed independently during the semester in those two residence halls.”

The researchers say that while move-in testing that took place as students arrived on campus was relatively fast (especially given how limited testing was most everywhere at the time), if the university had implemented a quarantine period while test results were pending it may have helped limit early spread.

More frequent testing at the start of the semester may have helped, too, Currie says. At the start of the fall semester, residence hall students were required to test once every two weeks, or more frequently if they experienced symptoms. During the outbreak, the university increased testing frequency and maintained a weekly testing requirement for the duration of the hybrid semester.

The results informed the spring campus response to COVID-19, the study authors note: “Recognizing this potential for rapid spread, UW–Madison has modified their testing strategy for the Spring 2021 semester, increasing frequency of testing to twice per week for students living on campus and living off-campus in nearly zip codes and has reduced turnaround time for results to less than 24 hours.”

UW–Madison did not experience a large outbreak in spring 2021. The researchers caution against generalizing the findings to other settings or even other on- or off-campus housing on the UW–Madison campus, however.

The CDC/UW–Madison partnership was “one of the most comprehensive partnerships that we had with universities in fall 2020, just because of the breadth of the work we did with the university,” Currie says. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services was also involved and co-authored the preprint. “It was a good opportunity to learn … how COVID-19 transmission was occurring.”

And, Currie says, the opportunity to combine traditional data about the spread of an infectious disease with a relatively high-level of genomic sequencing was unique: “They can complement each other and help identify pieces of the puzzle that one alone wouldn’t be able to do.”

The research relied on support from UW–Madison; the Advanced Computing Initiative; the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation; the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery; and the National Science Foundation, an active member of the Open Science Grid, supported by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. It was also supported by the Computation and Informatics in Biology and Medicine Training Program (NLM 5T15LM007359) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Contract #75D30120C09870: Defining the Role of College Students in SARS-CoV-2 Spread in the Upper Midwest.

Working with University Health Services and the CDC, researchers at the AIDS Vaccine Research Laboratory at UW–Madison sequenced 262 full viral genomes from samples collected from students in two large residence halls who tested positive for COVID-19. In A. above, the pink and blue circles show the viral genomes associated with the residence hall outbreak, while the gray circles are viral genomes found elsewhere in Dane County. A study shows that interventions to contain the outbreak likely helped prevent spillover of the outbreak into Dane County. The pink box in A. shows a unique virus lineage that appeared in the residence halls and ceased to spread after the quarantine. Figure: Center for Disease Control and Prevention study

Tags: covid-19, health & medicine, research