New model reveals possibility of pumping antibiotics into bacteria

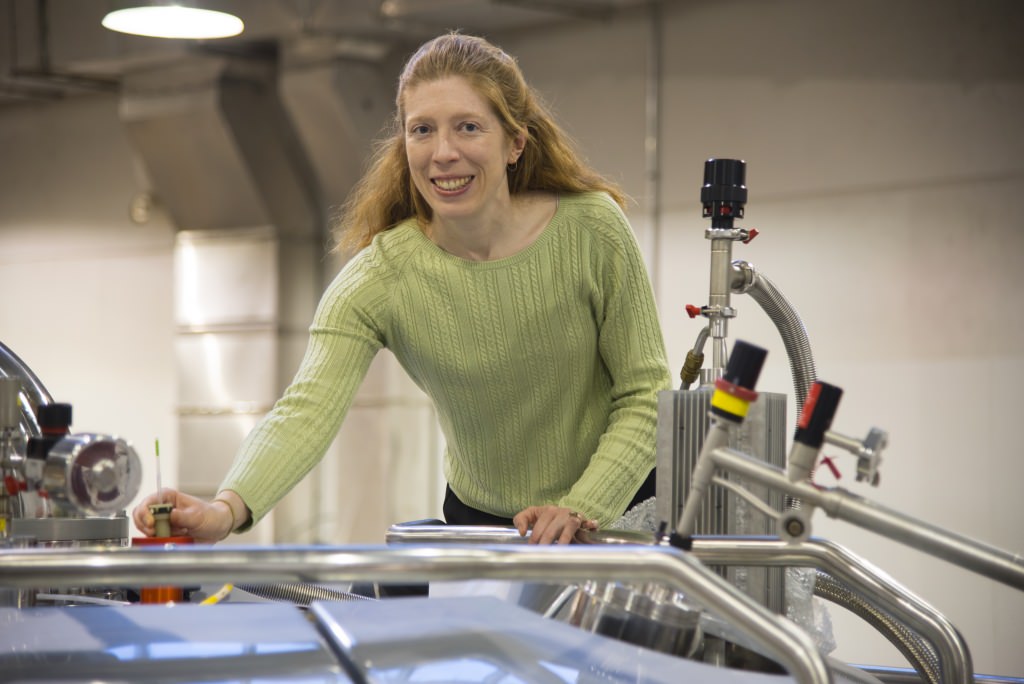

Biochemistry professor Katherine Henzler-Wildman in the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, housed in UW–Madison’s Department of Biochemistry. UW–Madison/Robin Davies

Researchers in the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Biochemistry have discovered that a cellular pump known to move drugs like antibiotics out of E. coli bacteria has the potential to bring them in as well, opening new lines of research into combating the bacteria.

The discovery could rewrite almost 50 years of thinking about how these types of transporters function in the cell.

Cells must bring in and remove different materials to survive. To accomplish this, they utilize different transporter proteins in their cell membranes, most of which are powered by what is called the proton motive force. The proton motive force is directed toward the inside of the cell in bacteria, which means that protons naturally want to move in to the cell from the outside and do so if there is a pathway for them. These transporters allow the measured movement of protons into the cell — and in exchange for protons moving in, drug molecules get expelled.

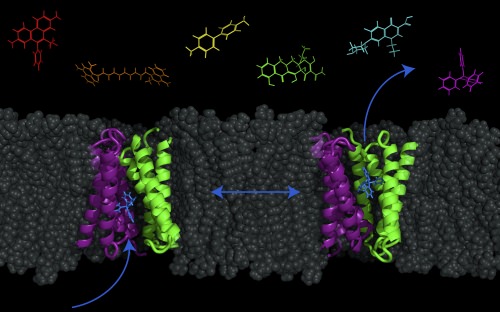

It was long thought that this coupled exchange of protons (in) and drugs (out) by the transporter was very strict. However, in a study published today (Nov. 7, 2017) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, UW–Madison biochemistry professor Katherine Henzler-Wildman and collaborators at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that for E. coli’s small multidrug resistance transporter, called EmrE, proton and drug movements are not as strictly coupled. This transporter can actually also move drugs and protons across the membrane in the same direction, as well as the opposite direction — introducing the option of moving molecules both into or out of the cell.

A transporter protein — called EmrE, shown in purple and green — in the cell membrane of E. coli bacteria can be switched between two conformations in order to pump molecules (such as antibacterial drugs) out of or into the cell. Image courtesy of Katherine Henzler-Wildman/UW–Madison

This minor detail has big implications, the researchers say. The models scientists have used for almost 50 years to visualize how these transporters work does not account for the new data. It also means that it might be possible for drugs to be pumped into the cell.

“The long-term implications are that this multi-drug transporter is reversible,” Henzler-Wildman says. “So instead of pumping drugs out to confer resistance, you have the possibility that you could use it to pump drugs in to kill bacteria. Drug entry is a big problem, so this is a new area to explore.”

She adds that this study and her previous work suggest that by manipulating the environmental conditions or the drug itself, the researchers may be able to control not only the rate of the transport but also its direction — at least in test tubes in the lab. Trying to confirm this in bacteria is one of the next steps in their research, she says.

“We started with a very basic science question of ‘how do these transporters work?’ and have stumbled upon this really translational direction,” she says. “People have been trying to target these kinds of pumps to stop antibiotic resistance to make antibiotics that we already have effective again. This suggests that you might be able to not just stop it but actually use these pumps to drive drugs into the cell as a new drug entry mechanism.”

This particular transporter is found in many bacteria. Surprisingly, scientists don’t yet know its real function in the cell. While it does pump out antibiotics, it is not the main transporter that aids E. coli in antibiotic resistance, and it’s possible it has other purposes still undiscovered. They have only found that is transports a large number of molecules from dyes to antibiotics.

“Bacteria are constantly at war with each other, so maybe it does play a role in drug resistance,” Henzler-Wildman says. “But it could also transport something else we haven’t tested, or maybe it works in pH resistance. We haven’t narrowed it down yet.”

“Having to rework the model and essentially rewrite the textbook on what we knew about the transporters will really change the way we think.”

Katherine Henzler-Wildman

Traditionally, the model used to describe this transporter was the “pure-exchange model,” which required the strict, regimented movement of protons and the drug in opposite directions. However, the reality of this process follows the mantra of “life is messy.”

Henzler-Wildman is proposing a new model called the “free-exchange model,” where the combinations and direction of transport are much more flexible with many more options than previously thought. They used magnetic resonance data to visualize these specific and previously unknown movements of the transporter. Then they studied how exactly the transporter responds in the test tube when, for example, it’s exposed to antibiotics, in order to confirm it works the way the structures showed.

“Having to rework the model and essentially rewrite the textbook on what we knew about the transporters will really change the way we think,” she says. “I’m actually going to teach this paper in our intro graduate course because it’s such a good story of how having a model in your head can limit your thinking and experiments and you really miss important things.”

This research was supported by Institutes of Health Grant 1R01GM095839, National Science Foundation graduate research Fellowship DGE-1143954, and a Mr. and Mrs. Spencer T. Olin fellowship for Women in Graduate Study.