Mother-of-pearl’s genesis identified in mineral’s transformation

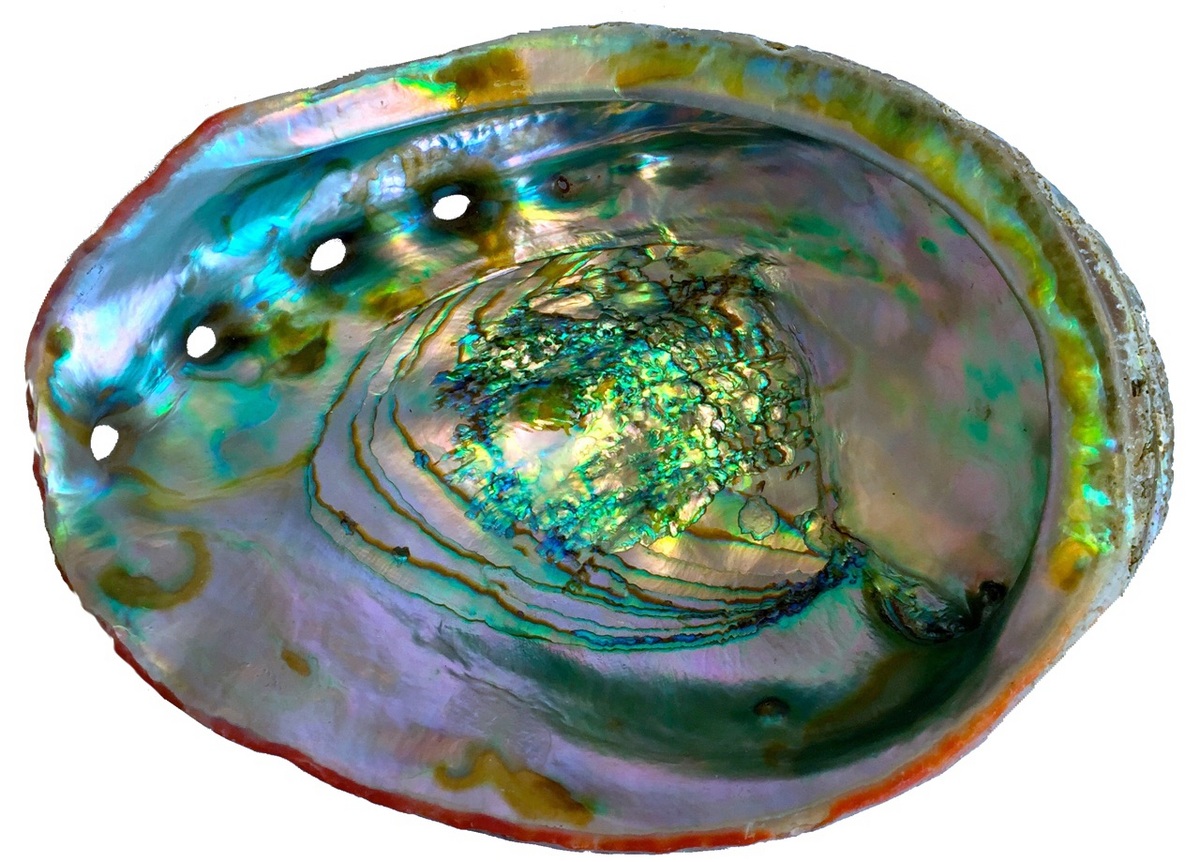

The red abalone makes the lustrous but hard-as-nails nacre lining of its shell by changing the atomic structure of amorphous calcium carbonate. Also known as mother-of-pearl, nacre has been worked by humans for millennia to make jewelry and fancy inlay for furniture and musical instruments.

Photo: Pupa Gilbert

How nature makes its biominerals — things like teeth, bone and seashells — is a playbook scientists have long been trying to read.

Among the most intriguing biominerals is nacre, or mother-of-pearl — the silky, iridescent, tougher-than-rock composite that lines the shells of some mollusks and coats actual pearls. The material has been worked by humans for millennia to make everything from buttons and tooth implants to architectural tile and inlay for furniture and musical instruments.

But how nacre is first deposited by the animals that make it has eluded discovery despite decades of scientific inquiry. Now, a team of Wisconsin scientists reports the first direct experimental observations of nacre formation at its earliest stages in a mollusk.

Pupa Gilbert

Writing in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, a team led by University of Wisconsin–Madison physics Professor Pupa Gilbert and using the U.S. Department of Energy‘s Advanced Light Source at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory describes the precursor phases of nacre formation at both the atomic and nanometer scale in red abalone, a marine mollusk with a domed shell lined with mother-of-pearl.

“People have been trying to understand if nacre had an amorphous calcium carbonate precursor for a long time,” explains Gilbert, an expert on biomineral formation, referencing the non-crystalline calcium carbonate observed to set the stage for nacre formation. “There is just a tiny amount of amorphous material. It is very hard to catch it before it transforms.”

Gilbert and her colleagues, using the synchrotron radiation generated by the Advanced Light Source, employed spectro-microscopy to directly observe the chemical transformation of amorphous calcium carbonate to the mineral aragonite, which manifests itself as nacre by layering microscopic polygonal aragonite tablets like brickwork to underpin the lustrous and durable biomaterial. “We could only capture it in a handful of pixels, about 20 nanometers in size, at the surface of forming nacre tablets,” says Gilbert of the way the mollusk deposits hydrated amorphous calcium carbonate, which rapidly dehydrates and then crystalizes into aragonite.

“Amazing chemistry happens at the surface of forming nacre.”

Pupa Gilbert

“Amazing chemistry happens at the surface of forming nacre,” says Gilbert, noting that the transformation of amorphous calcium carbonate into crystalline aragonite involves calcium atoms, initially bonded to six oxygen atoms, and ultimately to nine in the crystalline biomineral. “It is how the atoms are arranged that matters. The actual chemical composition of calcium carbonate does not change. Only the structure does upon crystallization.”

That was the big surprise, observes Gilbert: “The change in atomic symmetry around calcium atoms, from six to nine oxygen atoms, surprised us. Everyone expected to find amorphous precursor minerals that already had the symmetry of the final crystal at the atomic scale, lacking only the long-range order of the crystals. We stand corrected.”

Gilbert says the new, detailed understanding of how nature makes mother-of-pearl may one day lend itself to industrial application. Highly durable bone implants are one example, and the material is also environmentally friendly.

Support for the study by Gilbert and her colleagues was provided by the DOE and the National Science Foundation.