Games no laughing matter as science teachers, designers work together

“Is creating something to kill everybody on the planet a compelling game concept, or is it too close to reality?” asks David Gagnon, during the early hours of a recent game-design workshop at the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Wisconsin Institute for Discovery (WID).

The question may seem unusual in academia, but then everything was on the table as seven Wisconsin middle school science teachers collaborated with the Field Day Lab, a group of experienced UW–Madison game designers.

Learning by doing is central to the lab’s philosophy, says Gagnon, the director. “Why give people games when they can create games?”

A group of Wisconsin middle-school science teachers work in teams as they collaborate with UW–Madison staff and experienced computer game designers during a workshop at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery. Photo: Jeff Miller

Games, to Gagnon, are not just a matter of, well, fun and games. Instead, they are a teaching tool with advantages over textbooks and discussion, at least for some topics. “Games are made for the kind of process issues that are at the heart of science,” he explains.

And if you want to create science games for middle school students, he asks, what better source of expertise than middle school science teachers?

To get started, the teachers proposed fundamental scientific concepts from their curriculum and quickly began wrestling to transform them into games that challenge players while still teaching some science.

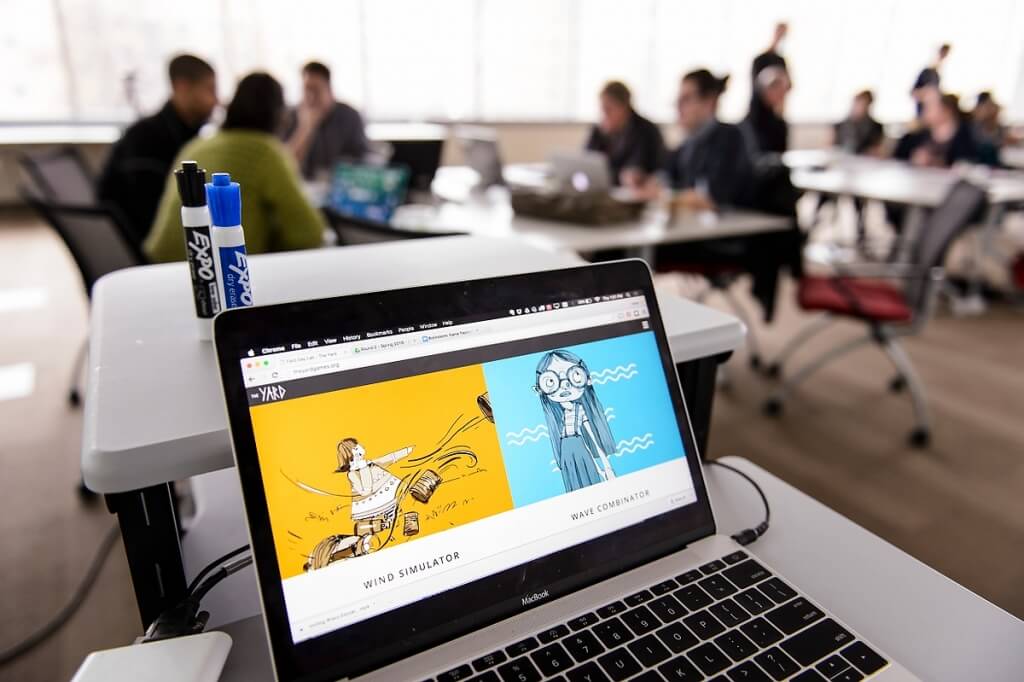

Two previously-developed computer games — Wind Simulator and Wave Combinator — are displayed on a laptop during the Field Day Lab mini-game design workshop. Photo: Jeff Miller

“When we say ‘food web,’ what are we are dealing with?” Gagnon begins. “The flow of energy in an ecosystem,” says one teacher. “Producers, consumers and decomposers,” says another. “Predators and prey: One population increases at the expense of another, which decreases,” adds a third.

“I like to hear a system like that,” says Gagnon. “That’s game stuff. Science is about systems, not just knowledge, and we can use interactive media to teach systems.”

The strategy for developing “game stuff” involves blending the experience, skills and creativity of two groups that don’t typically hang out together: game creators and science teachers. “Our goal is to add a layer of experiential design, content and playfulness for people who are exploring scientific topics,” Gagnon says.

Games, to David Gagnon, are not just a matter fun and games. They are a teaching tool with advantages over textbooks and discussion. Photo: Jeff Miller

The year-old Field Day Lab is an interdisciplinary team of educational researchers, software engineers, artists and storytellers that specializes in games, fieldwork and learning through making. Gagnon and colleague Jim Mathews met as graduate students of Kurt Squire, professor of digital media in the UW–Madison Department of Curriculum and Instruction. The workshop and ensuing game development are funded by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and the Wisconsin Virtual School, which offers online courses to middle and high school students.

As the workshop progresses, it moves inexorably from the abstract toward the concrete, as Gagnon inquires, “How do you currently teach the food web?” Every game needs a challenge, he adds. “How do you win? What are the verbs? How does this happen? What are the ‘knobs’ that the player will adjust?”

Wisconsin middle school science teachers Jeanine Gelhaus and Matt Regan brainstorm ideas. Photo: Jeff Miller

“The easy part is the concept,” says Jeanine Gelhaus, an 8th grade science teacher from Medford, Wisconsin. “The science part we know, but to turn it into a game is a lot more challenging than I thought.”

As expected, Gelhaus brings her on-the-job experience to the workshop by suggesting, “If we return their results at the end of each round, the students can make an informed decision for the next round.” In her mind, she says, “I’m going back to my classroom to check: Would they be learning what I want them to be learning?”

As different combinations of teachers and Field Day staff work through a series of concepts, Gagnon, Mathews and other lab members provide guidance in the difficult transformation from scientific concept to game.

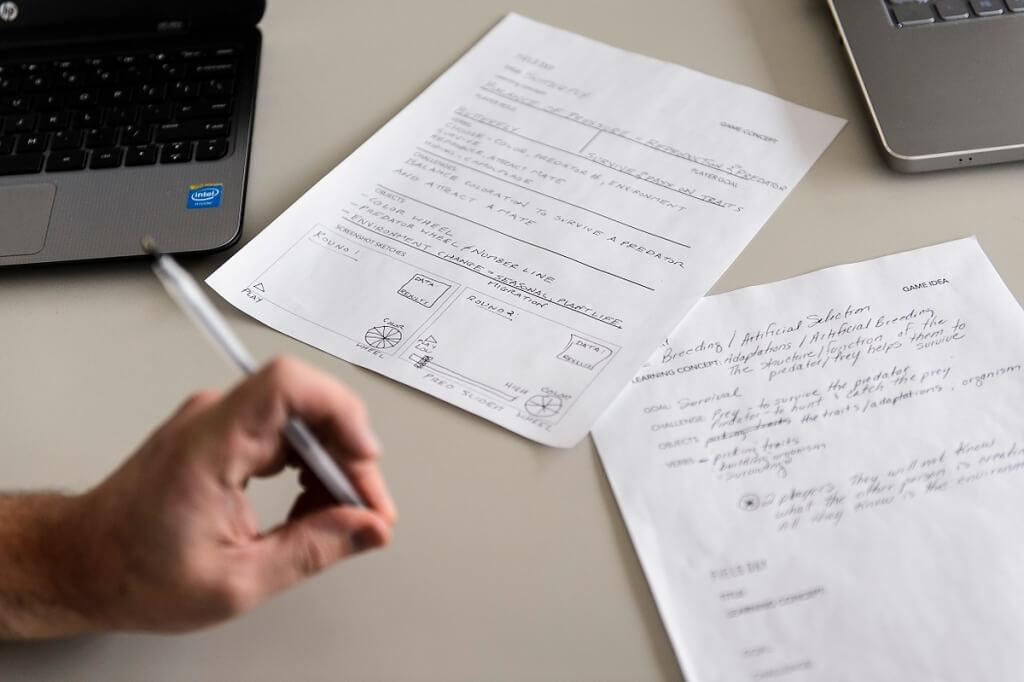

Collaborators shared notes on game ideas and concepts, listing goals and challenges while sketching out suggested screenshots. Photo: Jeff Miller

The collaboration seemed productive, says Joe Riederer, who teaches at Wisconsin Rapids Area Middle School. “I was a little intimidated as I do not know much about game design, but my ideas are being listened to. I have been treated as if I bring something of value, and that’s a big morale booster.”

Beyond their educator-heavy origins, the Field Day games are also distinguished by their reliance on open source software, says Gagnon. “We are creating free and open educational resources that can be used by anyone on the planet, and specifically by Wisconsin educators.”

The Field Day Lab is developing some of the game concepts that were born in the session at WID, and during development, the same teachers will be tapped as beta testers and expert advisors, Gagnon says.

“By engaging science teachers right from the start, we want to build games that will actually be used in classrooms. Too many games languish because they do not fit what teachers want. With the teachers’ help, we want to build them right — right out of the gate.”

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.