Fermenting a winner: Class brews up “Red Arrow American Pale Ale”

Instructor Hans Zoerb (left) and student Leo Gallagher pour malted barley into the mash tun at the UW–Madison Craft Brewery in Babcock Hall at UW–Madison, starting the brewing process for one of the six beers that were considered for production this spring. David Tenenbaum

A spooky silence pervaded a classroom at Babcock Hall on the UW–Madison campus Feb. 8 as a couple dozen students focused with laser-like intensity on a cultural and economic mainstay of Wisconsin: beer.

Amid the hush of anticipation, five experienced judges sipped six offerings from Food Science 551, Food Fermentation Laboratory.

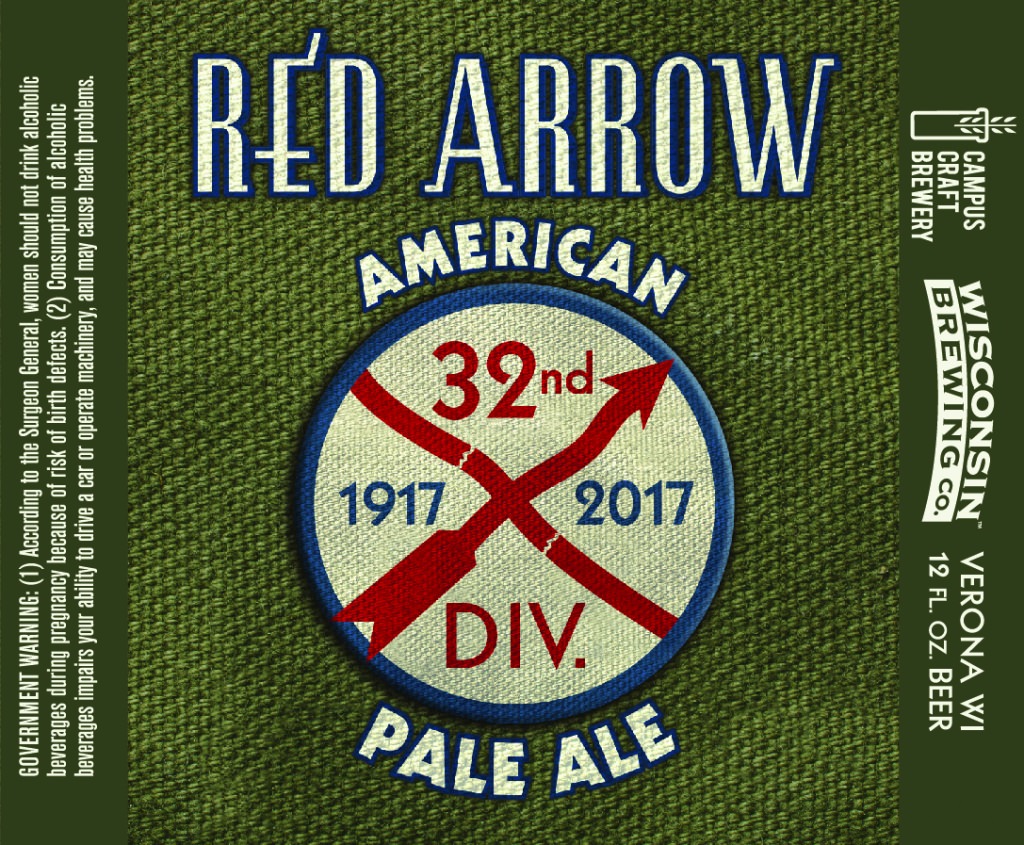

Each of the test beers was brewed at Campus Craft Brewery in Babcock Hall. The winner, called “Red Arrow American Pale Ale,” has now been brewed in larger quantity at Wisconsin Brewing Co. in Verona, and will be served at Memorial Union starting April 28.

After each of the student teams described their beer and answered technical questions about yeast, hops, malt and timing, the judges retired to mull over the brews.

Kirby Nelson and Suzanne Thompson at work judging beers during the Campus Craft Brewery competition. Thompson, a Food Science graduate, manages quality systems and regulatory compliance at MillerCoors in Milwaukee, and oversees the corporate analytical and sensory labs. David Tenenbaum

Some were the best of beers. Some were the worst of beers. All were identified by number only.

One beer, the judges decided, “smelled like they’d been cooking garlic and onion all week.”

Returning to the classroom, Kirby Nelson, brewmaster at Wisconsin Brewing, gave the verdict. “No. 6 was very brave, like the Red Arrow Division that fought through enemy lines. It pushes the color envelope, but it’s all malt, not enough hop,” and therefore, not an American pale ale.

Sample number one was the winner, Nelson says. “I loved it. It had good balance with the Galena hops, and probably the hoppiest aroma.” So that recipe — after some tweaking — was brewed at Wisconsin Brewing on March 15. Red Arrow American Pale Ale will be celebrated starting at 3 p.m. at Union South on April 28, and then around the state.

The name honors the Red Arrow Division, a ferocious fighting force largely comprising volunteers from Wisconsin and Michigan that achieved distinction a century ago. According to Wikipedia, “The Division’s shoulder patch, a line shot through with a red arrow, symbolizes the fact that the 32nd Division penetrated every German line of defense that it faced during World War I.”

Kirby Nelson, brewmaster at Wisconsin Brewing, Verona Wisconsin, sizes up one of the six beers being judged at Babcock Hall. David Tenenbaum

Red Arrow and the recipes for Inaugural Red and S’Wheat Caroline (both are for sale statewide) emerged from a class that began two years ago. The students come mostly from food science, chemical engineering and microbiology. Their motives vary from exploring a hobby to getting a job.

Leo Gallagher, a senior in food science from Green Bay who helped write the recipe for brew No. 2, interned last summer at Octopi Brewing in Waunakee. “I wanted to learn more about brewing at the industrial scale, because I’m hoping to find a full-time job in brewing once I graduate,” he says.

Gallagher says his previous home brewing used kits, “so I enjoy finally getting to formulate on my own.” His group added rye, which, Nelson says, was “a very nice touch, a nice fruity aroma.”

As water and malted barley were cooked in a container called a mash tun, sugar was extracted from the malt, instructor Hans Zoerb says. “It’s like steeping tea leaves in hot water to get out the flavors.” Zoerb, who worked as a protein chemist at Pillsbury and Cargill in Minnesota, taught the brewing class in conjunction with James Steele, a professor of food science.

In the next container, the lauter tun, the grains are separated from the sugary water and finally, in the brew kettle, the liquid — now called “wort” — is boiled for sterility. The all-important hops are added at this stage, Zoerb says. “If you add hops early in the boil, they are mainly for bittering. If you add hops later, called ‘dry hopping,’ they are more for flavor and aroma.”

Equipment in the Campus Craft Brewery was donated by MillerCoors, and it symbolizes the brewing giant’s strong interest in the students and programs at UW–Madison, says Tobin Eppard of MillerCoors’ corporate brewing section, with responsibility for brewing and fermentation science. “We want to provide resources back to the university, so when graduates mature into the career world, they will look at us as an opportunity.”

“We are building relationships with professors to continue the dialogue, for internships and employment for young food scientists, fermentation scientists,” says Eppard, who visited the Food Science Department in March with Andrew Lefeber, a management trainee at MillerCoors in Golden, Colorado.

Lefeber, a New Holstein, Wisconsin, native, was already a home brewer when he entered UW–Madison. “I chose food science through a long process of elimination,” he says. “I wanted a job immediately after graduation. And brewing is a wonderful example of culinary art meets science to form a product I love.”

During his 18-month training, he says, “I am working in every part of the brewery and the entire supply chain, so I will know the upstream and downstream impacts.”

Eppard sees Lefeber as an example of why the company wants to augment its relationship with UW–Madison. “Andrew will take the science core that was so well-created at Madison and figure out what is important to MillerCoors. He will understand what it means to be in the shoes of a solid citizen brewer who works for hourly wages. His job will be to give away his knowledge. This will give him the capability to lead.”

Tags: food science, students