Conservation areas threatened nationally by housing development

Conservationists have long known that lines on a map are not sufficient to protect nature because what happens outside those boundaries can affect what happens within. Now, a study by two UW–Madison scientists in the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology measures the threat of housing development around protected areas in the United States.

In a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Volker Radeloff, an associate professor, and Anna Pidgeon, an assistant professor, looked at housing around every national park, national forest and federal wilderness area in the 48 contiguous states. Using data from the U.S. Census and local sources, they counted housing units built within 1 to 50 kilometers of these reserves, and produced maps and statistics that document the change since 1940 and project forward to 2030.

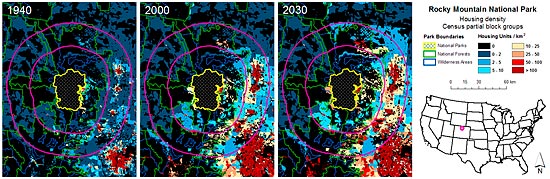

In a new study, Volker Radeloff and Anna Pidgeon of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology examined housing trends around conservation areas in the lower 48 states. This graphic shows the Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado in relation to two former periods and one projected period of expanding housing density. The purple lines outline areas within 25 and 50 kilometers (15.5 and 30 miles) of the Park; red shows areas with densest housing (actual figures for 1940 and 2000), with a projection for 2030.

In 2000, 38 million housing units were within 50 kilometers of these conserved lands, compared to 9.8 million in 1940, and housing was growing faster inside that 50-kilometer range than outside it.

A house’s sphere of influence extends beyond its own lot, because housing can encourage the spread of invasive species, alter drainage patterns and foster increased recreational use of the conserved land, which can, ironically, harm wildlife.

Ground-nesting birds are particularly vulnerable to houses and the dogs and cats they contain, as well as to the raccoons, opossum and skunks that are attracted to residential areas, says Pidgeon. The affected species in Wisconsin’s northern forest include the ovenbird and black and white warbler.

Many of the effects of housing are unintended, Pidgeon observes. “People are not building houses intending to kill cougars, but that may be the effect if a cougar starts to threaten children and has to be removed.”

Migratory animals such as elk need to summer in the mountains and winter in the valleys, Pidgeon notes. “But in the Cascades, the valleys are now filled with orchards and houses.”

Another area of concern is light pollution, Radeloff adds. “People don’t always think about this, but a lot of wildlife species base their way-finding on the stars or the moon, and a lot of outside light can be confusing and harmful.”

The ranges under study, from 1 kilometer to 50 kilometers, were not magic numbers, says Radeloff. “We wanted to capture the range of threats.”

In general, the closer the house, the higher the impact, he notes. Houses within a kilometer of a preserve can be destroyed by wildfires that start inside the conserved area, “so the manager of a wilderness area might decide to fight a fire instead of letting this natural process run its course. If the house burns, the manager might be in trouble.”

One category of development that jumped out of the data was the 940,000 housing units built between 1940 and 2000 in private land inside the boundaries of national forests. These so-called “in-holdings” are surrounded by conserved land and therefore pose a special challenge for wildlife.

The Wisconsin scientists project that housing within 50 kilometers of wilderness areas will have grown 45 percent (10 million units) by 2030 compared to 2000. During the same period, they project housing to grow 52 percent within 1 kilometer of national forests.

The study was supported by the Northern Research Office of the U.S. Forest Service, Radeloff says. “They perceive housing as a big challenge for the management of national forests, because what happens right outside their boundaries is important for their future.”

As the Wisconsin scientists envision it, their new maps could be used to help local zoning groups make better decisions about land use, especially when high-value conservation land is a factor. “If you have an important wildlife corridor, it’s important to question further density,” says Radeloff. “It’s no secret that people like living near nature, that’s a good thing, but by building there, they may be affecting the very thing they sought out.”

Adds Pidgeon, “I was shocked to think that these protected areas aren’t doing the job we believe they were doing. There are now rings of housing around national parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite. I don’t think it’s occurred to people to think about how that may affect biodiversity. These parks, wilderness areas and forests are intended to protect biodiversity, so we need look at what is going on. We are in danger of loving these protected areas to death.”