Gymful of effort, smiles: Adaptive fitness proves exercise is for everybody

When Mike Elbing was a UW–Madison freshman two years ago, he was a bit anxious about his new class on adaptive fitness.

“I thought it would be depressing because we were around people with different abilities,” he says. “I did not think how happy everybody would be to be here.”

Then Mike gestures toward gym 6 at the Natatorium on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus. “There’s a change of emotion going in there from out here. It’s given me a brand new perspective; you can take away someone’s legs and they can still have an incredible life.”

Stories about lives changed in an instant explain why many clients are in gym 6. A gas explosion. A 30-foot fall. Strokes. A spine-breaking diving accident.

When you talk to the clients, you see drive. Ambition. Perseverance. Openness. Oddly absent is self-pity.

Anne Nahn comes to class twice a week, and exercises for 20 to 60 minutes every day at home. Hard work pays off, she says. “Oh yes. I can walk with a cane now.” Gesturing to her head, she adds, “Things have got to get connected up there.” David Tenenbaum, University Communications

In Gym 6, limitations are considered temporary. Goals enunciated to encourage the long, hard work of recovery. Anne Nahn, a mother of eight who had a stroke while ski-patrolling at Devil Head, says she “almost bled to death, but I did make it. I will not give up. I want to go skiing again.”

Gym 6, stocked with squadrons of modified exercise equipment, is headquarters for the Adaptive Physical Activity Program. Housed in the department of kinesiology in the School of Education, each semester the program serves 100 clients like Nahn. It also teaches and inspires 270 to 300 students and student volunteers like Elbing, who has volunteered for five semesters because, essentially, it feels great to do good. “I started out wanting to be an athletic trainer,” he says. “Now I want to work with a more diverse group of people. You don’t need to be an athlete to work out.”

As Elbing indicates, coordinator and director Tim Gattenby expects that some of these students will change the way disabilities are viewed down the line. “We get pre-med students, nursing students, wanna-be chiropractors, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and engineers who want to find new ways to interface with exercise equipment. We want to produce optimal health for people with disabilities, but equally we’re a health and medical professional training ground. That symbiotic relationship, that interaction of client and student is creating a new type of health professional.”

Gym 6 has been molded by Gattenby’s confident, optimistic personality. He says his life was irrevocably changed when he broke both legs in a skydiving accident while in college. “The doctor said, ‘You will never be the same,’ and I thought, ‘Who are you to take my hope away?’”

The doctor was apparently envisioning a life chained to a recliner. Instead, Gattenby, who was already athletic, recovered and began to excel in endurance sports, chalking up a string of victories and high placements in Ironman triathlons and in events that are dramatically more grueling. Twice in a row, for example, he won the 500-mile Border to Border race across Minnesota.

Simply, the doctor’s grim pronouncement fed rebellion. “All that time I was driven by this medical professional saying you will never be the same,” Gattenby says.

When he started at UW–Madison 32 years ago, Gattenby began working with people we call “disabled,” a term he seldom uses. Today, as a distinguished faculty associate in kinesiology, he teaches four sessions of Adapted Fitness and Personal Training, as well as theory classes in adapted physical education and outdoor pursuits.

For clients, that can-do attitude, fueled by the individual attention of eager young college students, forms a mighty tool for confronting the predictable discouragement of a long recovery.

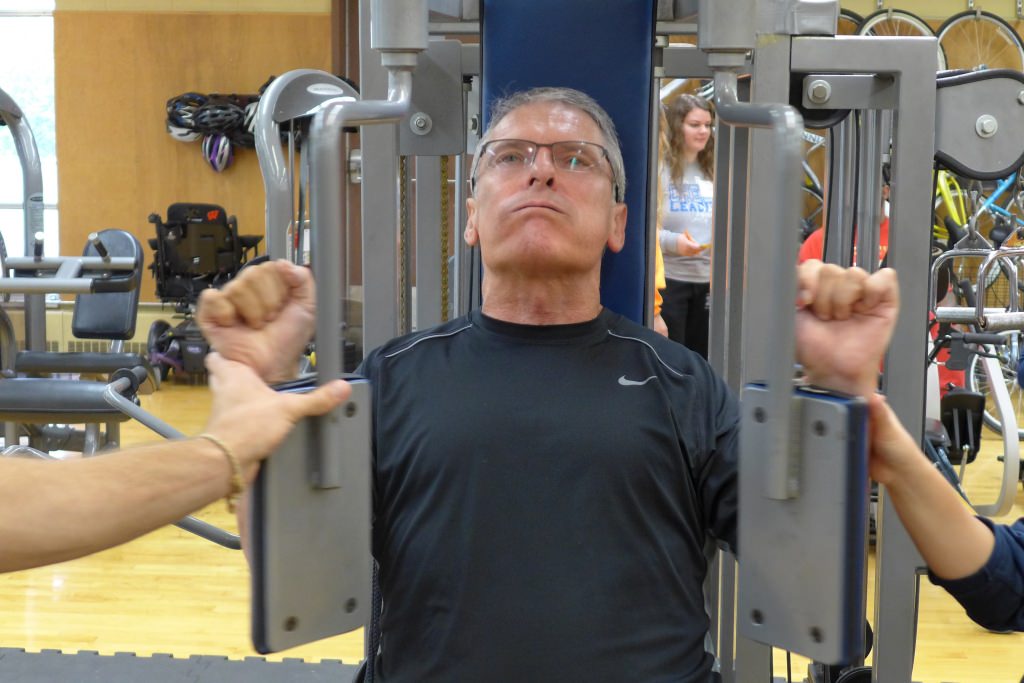

David Adams, a McFarland resident who suffered partial paralysis after a neck injury six months ago, was working on an exercise machine adapted for his weakened hand grip. “I’m doing things I could not do a month ago,” he says. The exercises are hard, but “good-hard.”

“Many of the students are changed because they develop an affinity, an ability to relate to clients because they get to know them so well,” Gattenby says. According to Lauren Sheahan, a senior in kinesiology and global health who has been volunteering for four semesters, “It became addicting to see clients and how much you are able to help change everyday things about their lives.”

The program includes a quiet but persistent activism, and Gattenby opens the class by suggesting that students testify at an upcoming City Council meeting on the paratransit program that provides mobility to many clients. “People with different abilities … are part of the diversity fight for rights, services and opportunities, and like everybody else, they are tired of not getting the same opportunities,” Gattenby says. “When it comes time to cut budgets, it seems like people with diverse ability are constantly taken from, and not given to.”

Laurel Sheahan, left, works with Diane Squire. Sheahan, a senior majoring in kinesiology and global health, says, “This program has shown me that all populations deserve the right to health. All aspects of public health need to be taken care of, including exercise.” David Tenenbaum, University Communications

Gattenby has refined his approach over the past 32 years. “I don’t give out a whole lot of information, because I want the student to get that from the client,” he says. “If you ask any client, ‘Who is the best physical therapist,’ they will say, ‘The one who listens to me, who is interested in me and my background.”

Certainly Gattenby was listening to the medical “experts” after his own brush with disability, though he rebelled rather than obey, then, in the process of healing himself, realized that he was not alone. As he puts it, “People with disabilities are being told things that don’t have to happen, that are not accurate.”