Veterinary medicine partnership with community saves baby crane

A young Wisconsin sandhill crane is back to full health and flying south for the winter thanks to a partnership between the UW School of Veterinary Medicine, Dane County Humane Society’s Four Lakes Wildlife Center, and a local wildlife rehabilitator.

In late July 2015, a baby crane was seen struggling to walk in Cherokee Marsh on the north side of Madison. A concerned observer brought the ailing bird to the center, where wildlife veterinarians and technicians gave her a thorough examination, including blood work and radiographs.

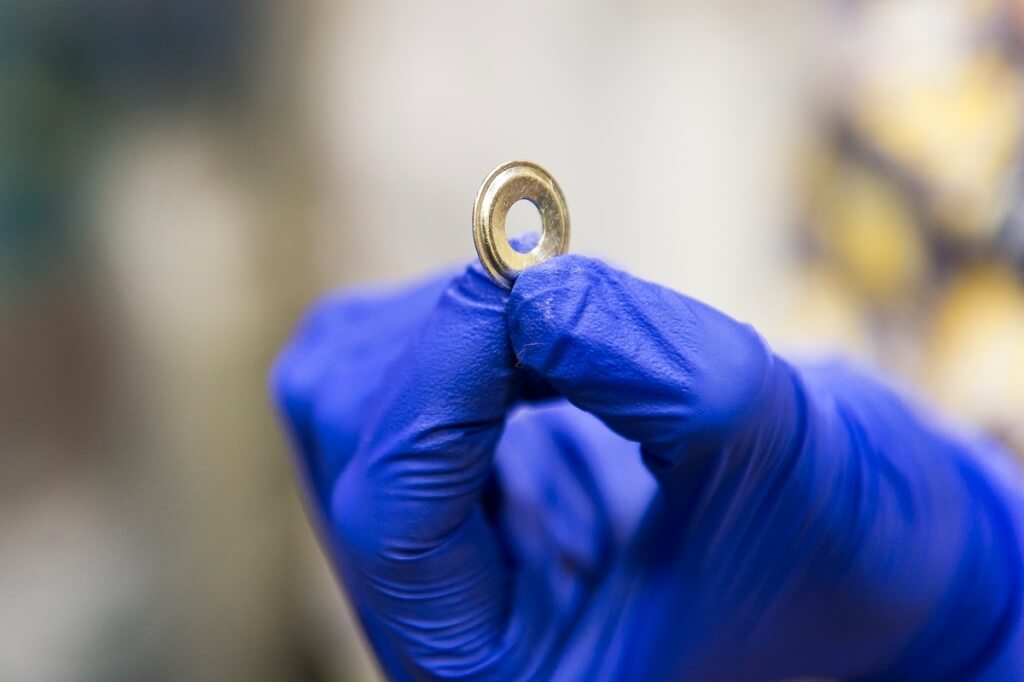

“We quickly discovered this baby crane had high levels of lead in her bloodstream as well as what looked like a metal washer stuck in her stomach,” says Brooke Lewis, a certified veterinary technician who serves as the center’s wildlife rehabilitation supervisor.

The radiographs made it clear the metal ring was too large to pass naturally, so Lewis and her colleagues referred the case to the UW Veterinary Care Special Species Health Service at the veterinary school. Christoph Mans, a clinical assistant professor and board-certified specialist in zoological and exotic animal medicine, recommended an advanced procedure for removing the piece of metal.

A highly-trained team — including the school’s Lily Parkinson, Terri Gregson, Tatiana Ferreira and Nicole Sinclair — performed the procedure, which involved inserting an endoscope (a length of tube with a light and camera affixed to its end) down the bird’s throat into its digestive tract. The veterinarians and technicians used the scope and the image it transmitted to a large screen as a guide to extract the ring with a long wire grasper.

“The endoscopic procedure is noninvasive and faster and safer than surgery, so it’s the treatment of choice for removal of foreign bodies from the stomach of most birds,” says Mans. “Minimizing stress and pain for our patients while under our care is very important to us.”

The metal disk, which turned out to be a grommet, proved tricky to grasp, but the procedure ended in success. The crane colt returned to the wildlife center for a short recovery before being transferred to the care of licensed wildlife rehabilitator Patrick Comfert. At his property in rural Rock County, Comfert helped the baby crane (or B.C., as she came to be called) associate with other cranes under his care.

“One crane in particular, named Jr., B.C. used as a surrogate mother,” says Comfert, who co-founded the center in 2002.

We quickly discovered this baby crane had high levels of lead in her bloodstream as well as what looked like a metal washer stuck in her stomach.

Brooke Lewis

With an adult crane to show her the ropes, B.C.’s recovery progressed well, Comfert says, and in early fall, she began taking short flights during the day. As the season progressed, she started foraging with local wild cranes and expanding her exploratory circle in preparation for migration. She also became less comfortable with human contact, a sure sign she was ready to re-enter the wild.

“She’s completely flighted now, so she can properly withstand wind and weather conditions,” says Comfert. “And she’s completely recovered from her issue. The last lead test we did showed very low levels.”

In late November, Comfert noticed B.C. and Jr. had stopped returning to his property at night. For the ultimate journey south, he assumes the young but newly molted sandhill and his “mother” joined up with either a mated pair of cranes that had spent the summer near his property or a separate local flock.

The partnership between the School of Veterinary Medicine and Four Lakes Wildlife Center has been a lifesaver for numerous animals like B.C., but it provides many other benefits for all involved. For example, in addition to taking referral cases, faculty, residents and students from the school’s Special Species Health Service volunteer several hours every week at Four Lakes, providing veterinary medical care for sick or injured wildlife.

“This close partnership with FLWC expands the variety of animal species and diseases that our students and residents learn from while increasing the diagnostic and therapeutic options for wildlife patients,” says Mans. “In addition, we perform clinical research studies in collaboration with FLWC to add to our knowledge on how to provide the best possible care to wildlife patients at rehabilitation centers.”

She’s completely flighted now, so she can properly withstand wind and weather conditions. And she’s completely recovered from her issue.

Patrick Comfert

In the past year, UW–Madison veterinarians have lent their expertise to eagle and swan lead poisoning cases, performed surgical fracture repairs on raptors, used laparoscopy to examine internal organs in birds and reptiles, fixed numerous shell fractures in turtles, conducted several emergency surgical procedures, and provided frequent consultations for cases involving a wide variety of native Wisconsin wildlife. For these efforts, the humane society recently honored the Special Species Health Service with the Volunteer Veterinary Service of the Year Award.

“They have allowed us to provide a higher level of patient care for all medical patients, including introducing us to new procedures, tests, and treatments that further elevate the care our staff can provide,” says Lewis.

Tags: veterinary medicine, wildlife