In words and glass, collaboration unlocks birth of modern chemistry

Scientific glassblower Tracy Drier creates a kaliapparat, the focus of his historical research, inside his glass shop in the basement of the UW–Madison chemistry building. Photo: Bryce Richter

Hidden in the logo of the world’s largest scientific society, likely unknown to many members, is a triangular symbol telling the story of a partnership that drove the development of modern chemistry.

Now, in their own partnership, two University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers are telling that story, in words and glass.

Detail from logo of the American Chemical Society, featuring Justus von Liebig’s original triangular kaliapparat.

In an interdisciplinary collaboration, historian of science Catherine Jackson and scientific glassblower Tracy Drier are delving into the foundations of modern chemistry and its reliance on specialized glassware. Through historical research and the re-creation of iconic glass apparatus, Jackson and Drier aim to uncover the beginnings of Drier’s profession and its contribution to the field of chemistry as it matured in the 19th century.

Their principal subject: the kaliapparat, a delicate piece of glassware resembling a musical triangle decorated with five round bulbs. In the hands of one of history’s most famous chemists, Justus von Liebig, the kaliapparat ushered in a new method of analyzing compounds that was so influential that the apparatus is enshrined in the logo of the American Chemical Society.

“When I took the job here, nobody said that UW–Madison has one of the best scientific glassblowers in North America,” says Jackson, who was a chemist before she pursued a second doctorate in the history of chemistry, referring to Drier. “But it does.”

Catherine Jackson, a historian of chemistry, is working with scientific glassblower Tracy Drier to uncover the history of Drier’s profession and its impact on the development of chemistry. Courtesy of Catherine Jackson

That serendipity quickly led to a productive partnership that Jackson pursues alongside writing a book on the development of organic chemistry in 19th-century Germany and Drier fits in between his daily operation of the busy glass lab. While Jackson has traced Liebig’s instruction in glassblowing and his development of early kaliapparat prototypes, Drier has worked from historical sketches unearthed by Jackson to recreate Liebig’s apparatus and its successors.

Kaliapparats made by Drier and his glassblowing students now hang like ornaments around his workshop. While Liebig’s original piece is simple by today’s standards, Drier has had to practice to make some of its more sophisticated descendants, some of which have delicate internal tubing and complicated structures.

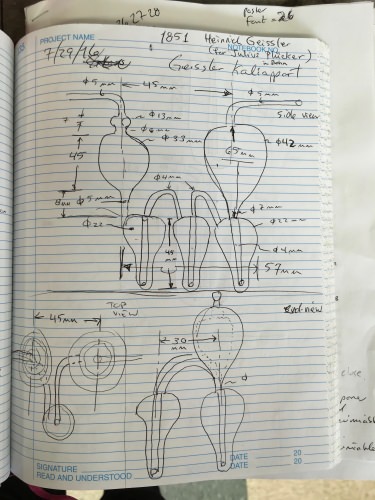

A sketch drawn by Tracy Drier of a kaliapparat designed by chemist Heinrich Geissler in 1851. This successor to Justus von Liebig’s original kaliapparat added more complicated tubing, requiring greater glassblowing skill. Photo: Eric Hamilton

While it is now taken for granted that skilled, technical glassblowers like Drier are essential to practicing chemistry, that was not always the case, says Jackson. Liebig’s development of the kaliapparat, and chemists’ increasing need for specialized glassware, tied together glassblowers and chemists in a partnership that continues to this day. Jackson wants to understand how that collaboration developed and why it was so important for chemistry.

“What Tracy and I have begun to do is to build a collaborative project which explains the origins of the professional scientific glassblower,” says Jackson. “We’re answering questions like: Why did chemists start to blow glass? What did blowing glass allow them to do that they couldn’t do before? When did they start to need somebody like Tracy?”

Liebig developed the kaliapparat in 1830 while trying to determine the elements making up morphine. The kaliapparat allowed Liebig to measure the amount of carbon in morphine by trapping the carbon dioxide produced from burning the drug. His success demonstrated to other chemists the value of learning glassblowing and working with professional glassblowers.

Several different versions of the kaliapparat and related glassware in Tracy Drier’s glass shop in the basement of the chemistry building. The development of modern chemistry required increasingly sophisticated glassblowing skills, provided by a new contingent of scientific glassblowers. Photo: Eric Hamilton

“This project gives me a really nice window on my profession,” says Drier, who received a 2016 Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Research for his contributions to the chemistry department. “To have Catherine be able to provide insight into why things have gone the way they have over time — you can’t imagine how exciting that is for me.”

The duo has shared their collaboration widely among historians, artists and glassblowers. Last fall, Jackson and Drier produced a public workshop on campus showcasing historical glassblowing methods, and this spring they presented at the Burdick-Vary Symposium hosted by UW–Madison’s Institute for Research in the Humanities. Next month, Jackson will address the American Scientific Glassblowers Society, whose journal, Fusion, featured a cover story on Liebig’s kaliapparat by Drier and Jackson in its February issue.

“We’re answering questions like: Why did chemists start to blow glass? What did blowing glass allow them to do that they couldn’t do before? When did they start to need somebody like Tracy?”

Catherine Jackson

Drier and Jackson plan to take their historical exploration a step further by using period-appropriate methods and materials to re-create historical glassware. This step back in time will help them understand the limitations overcome by chemists and scientific glassblowers at the dawn of what Jackson calls the “glassware revolution.”

“I’ve always been interested in the history of glassware,” says Drier, who, along with his brother — also a scientific glassblower — was originally inspired by his father’s glassblowing hobby as a child.

“It’s such a beautiful medium. And oh yeah, by the way, it can do everything.”

Not only does Tracy Drier work with professors on their new designs, he teaches graduate students the craft of scientific glassblowing. UW-Madison video

Tags: chemistry, history of science, science