Clarity of vision: Chemistry’s glass whisperer

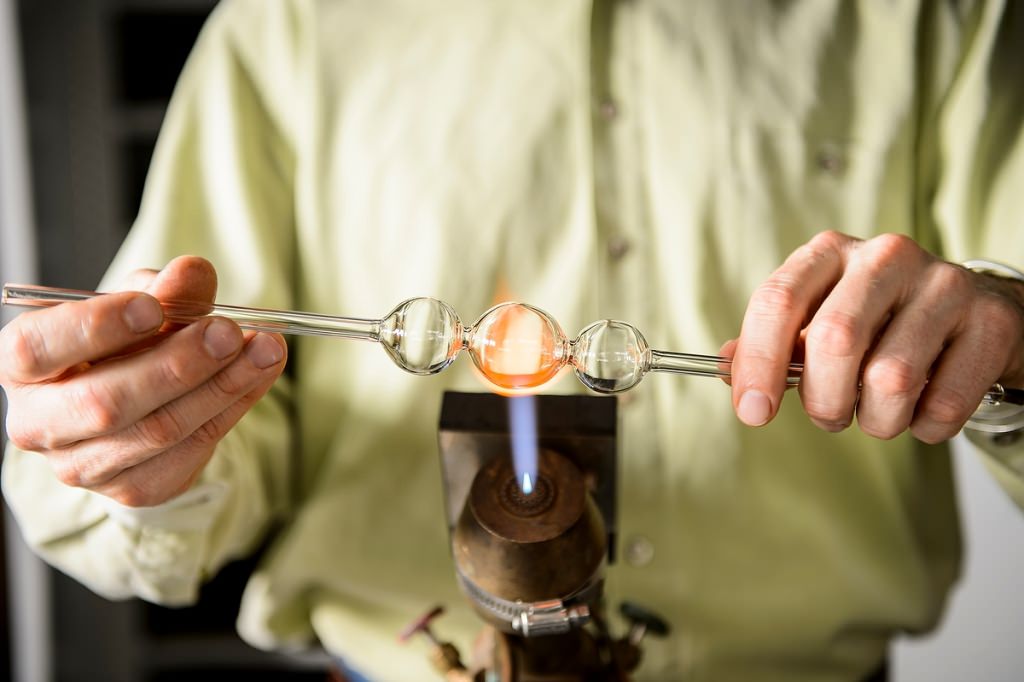

Tracy Drier, senior instrument specialist, creates a glass instrument in his shop in the Chemistry Building. Photo: Bryce Richter

In a lab built around tools and techniques that are more than a century old, Tracy Drier performs miracles of construction and reconstruction. When someone in the Chemistry Department breaks a piece of glassware, Drier and his panoply of torches and specialized equipment are ready to make a fix that can’t be detected by an untrained eye.

Tracy Drier

When a chemist walks in needing a piece of equipment that’s not available in a catalog, Drier is ready to interpret. “I typically work with grad students, who are the ones with specific projects that need my help. We work together to try to come up with solution. I can work from arm waving. I help translate arm waving onto paper and into glass.”

There’s no reason to spend time drawing projects on a computer, he says. “The main issue is that I’ll never see that job again. If I make a wonderful drawing … what’s it for?” The intake process is quaint, Drier admits. “My billing business is digital, but everything else is pretty analog, and I’m okay with that.”

Glass is a foundation of chemistry, Drier says, pointing to a reproduction of a glass analytical device built by Justus von Liebig in the 1830s. The “kaliapparat” is so essential that it is embedded in the logo of the American Chemical Society.

On a tour, Drier shows off the peculiar tools and equipment needed to work glassware. New projects usually start at a rack of tubes made of the same material found in fridge-to-oven glassware. Multiple 2,500 degree Celsius torches — with pointed or diffuse flames — are used to weld, bend and blow glass. Two lathes rotate cylinders for even heating. Various sanders and grinders are used for shaping and polishing.

“I can work from arm waving,” Drier says. “I help translate arm waving onto paper and into glass.” Photo: Bryce Richter

A bench devoted to large Dewar flasks — commercially termed thermos bottles — has vacuum pumps to evacuate these insulated containers needed for ultra-cold experiments.

Once a glass object is fabricated, the internal stresses created from heating must be removed before they can cause a break. Stresses can be seen with a device called the polariscope — a light box with polarized light that creates rainbow patterns that are hallmarks of dangerous stress. This stress is removed by annealing, a sequence of heating, holding and cooling in a kiln.

There’s no way to know how many Ph.D. theses and journal articles can be attributed to Chemistry’s soft-spoken glass whisperer. “I’m happy to do repairs,” he says, “but what I really like is the stuff where you actually have to think about construction, have to know something about glass.”

Tags: academic staff, chemistry, science