Fish-eyed lens cuts through the dark

Combining the best features of a lobster and an African fish, University of Wisconsin–Madison engineers have created an artificial eye that can see in the dark. And their fishy false eyes could help search-and-rescue robots or surgical scopes make dim surroundings seem bright as day.

Their biologically inspired approach, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, stands apart from other methods in its ability to improve the sensitivity of the imaging system through the lenses rather than the sensor component.

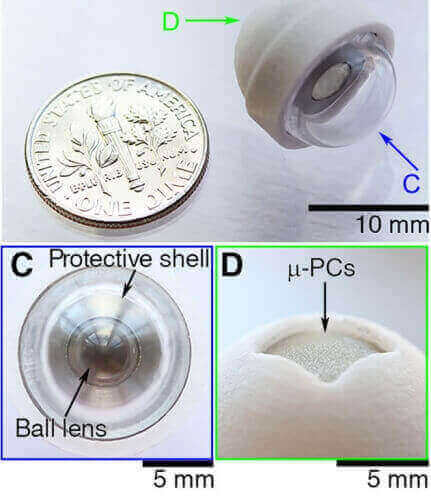

The ball-shaped, fingertip-sized artificial eye uses thousands of mirrors and a domed shape (seen in image D) to concentrate scant light. Image courtesy Hongrui Jiang

Amateur photographers attempting to capture the moon with their cellphone cameras are familiar with the limitations of low-light imaging. The long exposure time required for nighttime shots causes minor shakes to produce extremely blurry images. Yet, fuzzy photos aren’t merely an annoyance. Bomb-diffusing robots, laparoscopic surgeons and planet-seeking telescopes all need to resolve fine details through almost utter darkness.

“These days, we rely more and more on visual information. Any technology that can improve or enhance image-taking has great potential,” says Hongrui Jiang, professor of electrical and computer and biomedical engineering at UW–Madison and the corresponding author on the study.

Most attempts to improve night vision tweak the “retinas” of artificial eyes — such as changing the materials or electronics of a digital camera’s sensor — so they respond more strongly to incoming packets of light.

However, rather than interfering with efforts to boost sensitivity at the back end, Jiang’s group set out to increase intensity of incoming light through the front end, the optics that focus the light on the sensor. They found inspiration for the strategy from two aquatic animals that evolved different strategies to survive and see in murky waters.

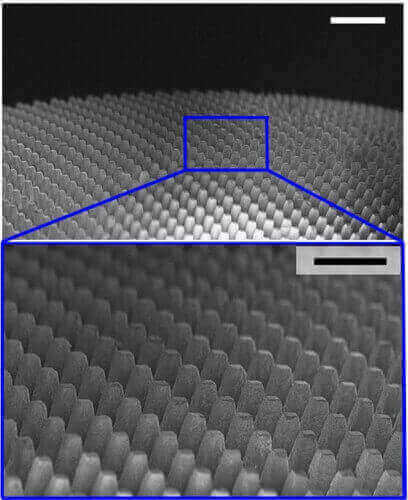

The field of tiny mirrors in the artificial eye was inspired by cup-shaped cells in the eyes of elephantnosed fish that help them see dark, murky water. Image courtesy Hongrui Jiang

Elephantnosed fishes resemble river-dwelling Cyrano de Bergeracs. Looking between their prominent proboscises reveals two strikingly unusual eyes, with retinas composed of thousands of tiny crystal cups instead of the smooth surfaces common to most animals. These miniature vessels collect and intensify red light, which helps the fish discern its predators.

“We were thinking: ‘Why don’t we apply this idea? Can we enhance the intensity to concentrate the light?’” says Jiang, whose research is supported by the National Institutes of Health and UW–Madison.

The group emulated the fish’s crystal cups by engineering thousands of miniscule parabolic mirrors, each as tall as a grain of pollen. Jiang’s team then shaped arrays of the light-collecting structures across the surface of a uniform hemispherical dome. The arrangement, inspired by the superposition compound eyes of lobsters, concentrates incoming light to individual spots, further increasing intensity.

“We showed fourfold improvement in sensitivity,” says Jiang. “That makes the difference between a totally dark image you can’t see and an actually meaningful image.”

In this case, the devices picked up a picture of UW–Madison’s Bucky Badger mascot through what seemed like pitch-black darkness. The device could easily be incorporated into existing systems to visualize a variety of vistas under low light.

“It’s independent of the imaging technology,” says Jiang. “We’re not trying to compromise among different factors. Any type of imager can use this.”

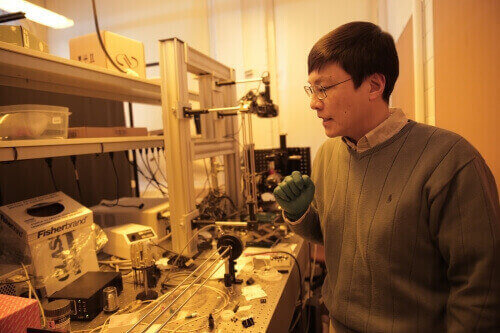

UW–Madison engineering Professor Hongrui Jiang describes the fabrication process for an artificial eye that makes better use of very dim light than any other optical sensor. Image courtesy Stephanie Precourt

Although superposition compound eyes are exquisitely sensitive, they typically suffer from less sharp vision. Increased intensity costs clarity when lots of light gets compressed down to individual pixels. To recover lost resolution, Jiang’s group captured numerous raw images and processed the set with an algorithm to produce crisp, clear pictures.

The engineers in Jiang’s lab — including Hewei Liu, the postdoctoral scholar who fabricated the lenses, and Yinggang Huang, who processed the super-resolution images — are working to refine the manufacturing process to further increase the sensitivity of the devices. With perfect precision, Jiang predicts that the artificial eyes could improve by at least an order of magnitude.

“It has always been very hard to make artificial superposition compound eyes because the curvature and alignment need to be absolutely perfect.” says Jiang. “Even the slightest misalignment can throw off the entire system.”

Tags: biosciences, engineering, research