Chazen becomes a resource for more than just art

Children from Sherman Middle School in Madison take notes while viewing African art and beaded works on exhibit at the Chazen Museum of Art. The group was participating in a project called “Africa Connects!”

As Russell Panczenko discusses the ways in which people use the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Chazen Museum of Art, the word “comfortable” comes up frequently — particularly in reference to students and visitors who are not art historians.

“Our mission, in alignment with the Wisconsin Idea, is very much to be a resource for the university and the people of Wisconsin,” says Panczenko, the museum’s director since 1984.

Works from the Chazen’s collection have brought an unexpected twist to the work of educators across campus and throughout the state.

“We’re always looking to the university, but the borders of the state are my reason for living,” says Anne Lambert, the longtime curator of education. “When we get a high school French teacher who comes down here from Rhinelander for a tour with one of our French-speaking docents, that’s a great day.”

“When we get a high school French teacher who comes down here from Rhinelander for a tour with one of our French-speaking docents, that’s a great day.”

Anne Lambert

With over 20,000 works spanning many genres, cultures and time periods, the Chazen boasts the second-largest art collection in Wisconsin. When its 86,000-square-foot expansion opened in 2011, it created literal windows onto the art world that draw in visitors from one of the most heavily trafficked areas of campus.

The expansion added resources rarely available at most museums, let alone free public collections. An object study room outfitted with glass cases allows curators to pull items from the museum’s collection to be viewed as long as they are needed by students, professors and others, including passersby who wander in during public hours.

Because of this accessibility, the museum may not always know how and by whom its collection is used.

Lambert hears bits and pieces: the geography professor who so enjoyed his breaks in the museum that he used a painting for the cover of his book; the climatology professor who called out Klaudii Lebedev’s The Fall of Novgorod, a favorite of many visitors, for its overly creative interpretation of snow.

The Fall of Novgorod by Klaudii Vasilievich Lebedev, 1891, oil on canvas. A climatology professor called out this painting, a favorite of many visitors, for its overly creative interpretation of snow.

Some faculty members return again and again to the museum as an educational resource. Mariah Quinn, an assistant professor in the School of Medicine and Public Health, chooses works such as David Wojnarowicz’s screen print “Untitled, 1992,” created when the artist was dying of AIDS, to spark discussion on topics such as bias in her Communication and Humanism in Medicine course for medical residents.

Horticulture professors Jim Nienhuis and Irwin Goldman co-teach what may be one of the few horticulture classes in the world that visits an art museum: Hort 370, World Vegetable Crops.

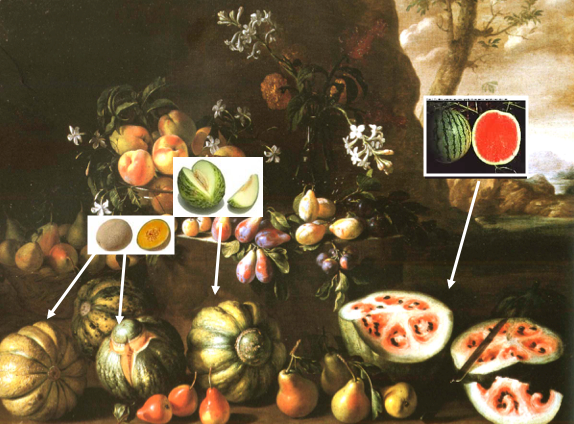

“Vegetables are perishable (as opposed to grains), and were domesticated prior to photography, but Renaissance art saves the day,” says Nienhuis. “We’re interested in the color, shape and sizes of the vegetables from 400 years ago, compared to modern cultivars of the same vegetables: the deep sutures on cantaloupe in Italian art of the Renaissance or the lack of pigmentation in pictures of watermelon compared to today.”

A painting’s age gives clues as to when the vegetables might have been introduced to Europe. Squash and tomatoes, for example, could only appear in European art after arriving from the Americas.

Giovanni Stanchi, Frutta e fiori con paesaggio marino. Italian, 15-16th century, annotated with modern examples by Jim Nienhuis, professor of horticulture, for his horticulture course World Vegetable Crops.

For English language learners in English 110 or 115, a trip to the Chazen allows them to practice their descriptive skills. Students from other countries — often from fields such as business or engineering — complete a writing assignment that stresses building blocks such as adjectival clauses.

Perhaps the best example of the museum’s use as the door to the humanities comes from the Odyssey Project, which provides six university credits for adult students facing economic barriers to college.

Before they begin yearlong discussions of great writers and thinkers, the students arrive at the Chazen on a Wednesday night when they have the museum all to themselves. They register for the course and receive their university ID cards surrounded by art — and the knowledge that they are welcome to explore some of the university’s most prized holdings.

The bare lobby offers a blank stage for dance, music and other demonstrations — all opportunities to bring more members of the larger community into the Chazen’s world.

One group of Odyssey students even contributed their own art to a major exhibition. When the Chazen presented “Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey” in the fall of 2013, Odyssey Project founder Emily Auerbach and several current and past students — many with personal connections to Bearden’s themes — presented at a symposium alongside professors and graduate students. Odyssey participants read poems mirroring the symposium’s title, “A Black Odyssey and the Quest for Self-Definition.”

To the Chazen’s staff, the more participatory the work, the better. The bare lobby offers a blank stage for dance, music and other demonstrations related to various exhibitions — all opportunities to bring more members of the larger community into the Chazen’s world.

“People want to see art, but they also have something to show,” says Panczenko. “That’s reiterating the phrase ‘You are welcome.’”

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.