Landscape change leads to increased insecticide use in the Midwest

The continued growth of cropland and loss of natural habitat have increasingly simplified agricultural landscapes in the Midwest. A Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC) study concluded that this simplification is associated with increased crop pest abundance and insecticide use, consequences that could be tempered by perennial bioenergy crops.

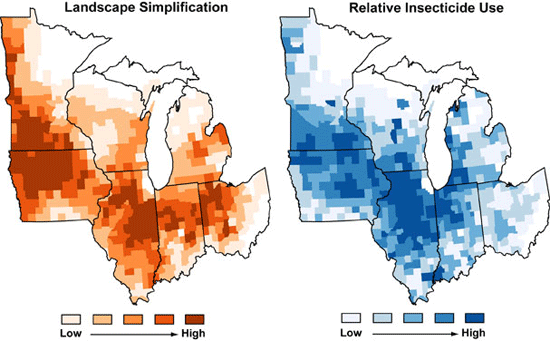

Simplified landscapes, with lots of cropland and little natural habitat, promote crop pest problems and increased use of insecticides.

Illustration: courtesy Tim Meehan, UW-Madsion

While the relationship between landscape simplification, crop pest pressure, and insecticide use has been suggested before, it has not been well supported by empirical evidence. This study, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences during the week of July 11, is the first to document a link between simplification and increased insecticide use.

“When you replace natural habitat with cropland, you tend to get more crop pest problems,” says lead author Tim Meehan, University of Wisconsin–Madison associate scientist in the Department of Entomology. “Two things drive this pattern. As you remove natural habitats you remove habitat for beneficial predatory insects, and when you create more cropland you make a bigger target for pests — giving them what they need to survive and multiply.”

Because landscape simplification has long been assumed to increase pest pressure, UW–Madison professor of entomology Claudio Gratton and Meehan were not surprised to find that counties with less natural habitat had higher rates of insecticide use.

One striking finding was that landscape simplification was associated with annual insecticide application to an additional 5,400 square miles in the Midwest — an area the size of Connecticut.

Although simplification of agricultural landscapes is likely to continue, the research suggests that the planting of perennial bioenergy crops — like switchgrass and mixed prairie — can offset some negative effects.

“Perennial crops provide year–round habitat for beneficial insects, birds, and other wildlife, and are critical for buffering streams and rivers from soil erosion and preventing nutrient and pesticide pollution,” says Doug Landis, Michigan State University professor of entomology and landscape ecology.

Perennial grasslands that can be used for bioenergy could also provide biodiversity support, specifically beneficial insect support, says Gratton.

“If we can create agricultural landscapes with increased crop diversity, then perhaps we can increase beneficial insects, reduce pest pressure and reduce the need for chemical inputs into the environment,” he says.

“We are at a junction right now. There is increased demand for renewable energy, and one big question is: where it will come from?” Gratton says. “We hope that these kinds of studies will help us forecast the impacts that bioenergy crops may have on agricultural landscapes.”

The Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center is one of three Department of Energy Bioenergy Research Centers funded to make transformational breakthroughs that will form the foundation of new cellulosic biofuels technology. The GLBRC is led by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, with Michigan State University as the major partner. Additional scientific partners are DOE National Laboratories, other universities and a biotechnology company.

The study was a collaboration between GLBRC researchers Meehan and Gratton of the UW–Madison, and Ben Werling and Doug Landis of Michigan State University.