‘Wisconsin Votes’ explores lively history of state voting behavior

Growing up in a politically divided house — with a Democratic mother and a Republican father — may have been one of the best things that could have happened to Robert Booth Fowler.

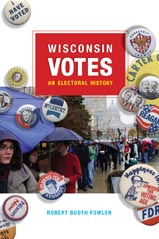

Robert Booth Fowler’s new book Wisconsin Votes: An Electoral History examines voting behavior from statehood in 1848 to the present.

“It tended to encourage me to think about (politics) sort of historically or analytically, rather than focusing so much on who I might be for,” says Fowler, a professor emeritus of political science. “So I was always interested in how things turned out and why.”

How things turned out and why is also a good description of Fowler’s new book Wisconsin Votes: An Electoral History, which examines voting behavior from statehood in 1848 to the present. And its publication by the UW Press occurs just as the state has once again emerged as a competitive battleground in the upcoming presidential election.

“I think Wisconsin’s so very difficult to predict because it’s a very close two-party state,” he says. “To me, it makes it a much more interesting subject … one-party states are boring. Wisconsin politics is not boring. Nor in my mind has its history been boring. We’ve had so many third parties — it’s all very fun.”

Those third parties include Progressives, the Prohibition Party and the Socialists. In more recent years, Green Party and Libertarian candidates have had an impact on elections even though they have not won statewide offices.

Fowler says the lesson for third parties from the state’s voting history is, “Wisconsin is open to you — and go for it — but it doesn’t mean you’re going to win.”

With the 2008 election fast approaching, Fowler’s account of voting in key elections as well as his investigation of electoral trends and patterns over the course of the state’s history could provide some clues for political pundits and campaigns trying to figure out how Wisconsin will vote in November.

“There are a number of issues where this state is a little bit more conservative than people might imagine,” he says, while adding that Wisconsin is just as liberal as some would expect on other issues, including the Iraq War.

“I think real people are often more complex than we give them credit for and so is their voting behavior,” Fowler says.

The book takes a closer look at votes on issues that sometimes explain more about the nature of the Wisconsin electorate than votes for candidates do. Hundreds of units that ordinarily vote Democratic strongly endorsed a referendum to amend the state constitution to ban same-sex marriages “despite the very clear message of the governor and others in the Democratic party that they were against it,” Fowler says.

“To me, the study of voting behavior is really the study of people: what they think, how they behave, what the culture is like,” he says. “And so, a lot of times, referenda are very revealing, because they tell you a lot quite apart from party issues.”

The interest that Fowler’s students have had over the years in studying their hometowns also contributed to the book’s exploration of how ethnic and religious groups have voted historically in Wisconsin and how they vote today. That doesn’t mean that the 43 percent of state residents who claim German ancestry all vote the same way, but areas of the state where certain ethnic groups bear a heavy influence do follow voting patterns, Fowler says.

“Show me an area that’s heavily German-American and I will show you a Republican area, generally,” Fowler says. “Traditions exist that have their roots in ethnicity.”