Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene works with campus partners to test for COVID-19

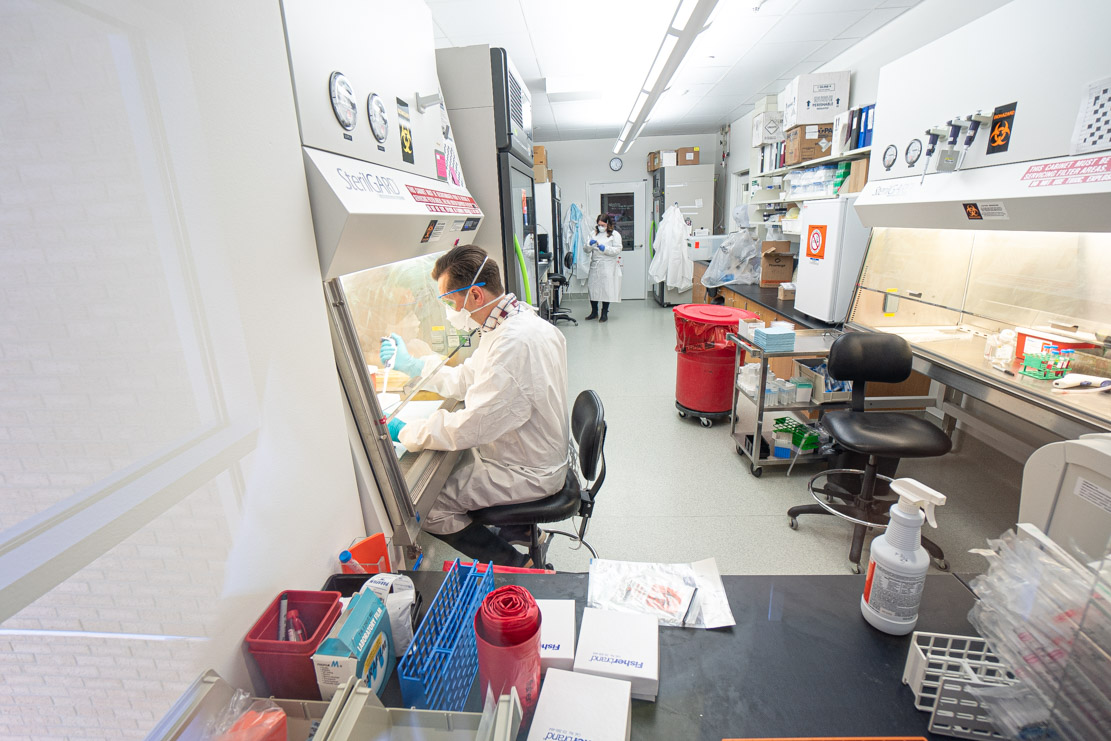

Erik Reisdorf, lead virologist at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, processes specimens for COVID-19 testing. Photo: John Maniaci, UW Health

As COVID-19 has infected more than 1 million people around the world — and more than 2,500 Wisconsin residents — since late December 2019, everything from nose-and-throat swabs to the chemical substances, or reagents, needed to conduct tests for the disease are in short supply.

Alana Sterkel, assistant director in the communicable disease division of the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, which has run thousands of tests for COVID-19 in the state, says we need more widely available testing to understand and curb the pandemic. Although the global surge in demand for testing materials has made the test harder to conduct in many places, WSLH’s colleagues at the university have pitched in to keep testing available in Wisconsin.

Testing for COVID-19 requires specialized equipment to help scientists and clinicians detect the virus and make enough copies of its genetic material to measure. The colored lines on the computer show the results of COVID-19 tests. Photo: John Maniaci, UW Health

Under normal conditions, the test is a straightforward lab procedure designed to home in on a specific virus.

Detecting virus in a sample from the nose or throat of an infected patient requires the ability to identify trace amounts of its genetic material using a process called polymerase chain reaction. For coronaviruses such as the one that causes COVID-19, this genetic material is a molecule called RNA.

Kyley Guenther, virologist at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, prepares respiratory virus specimens for the lab’s National Influenza Reference Center work. Photo: John Maniaci, UW Health

To do the test, scientists first need to convert the virus’s RNA into DNA, and this requires an enzyme to translate one type of genetic code into the other. The enzyme is called reverse transcriptase, and it was discovered in 1970 by UW–Madison virologist and Nobel Prize winner Howard Temin along with his colleague David Baltimore at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

It also requires a machine called a thermal cycler, which allows scientists to make many copies of the genetic material so there is enough of it to measure. Other reagents are necessary to stabilize and complete the reactions.

It would have been relatively simple to increase local testing capacity if the new virus hit only one part of the world. But that’s not what happened.

“Simultaneously, all across the globe, everyone was trying to purchase the same materials at the same time,” says Sterkel.

However, WSLH’s colleagues across the university have stepped up to help by donating some of the necessary reagents, supplies and more. One of its biggest partners has been the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, which has loaned equipment and reagents and provided training to WSLH.

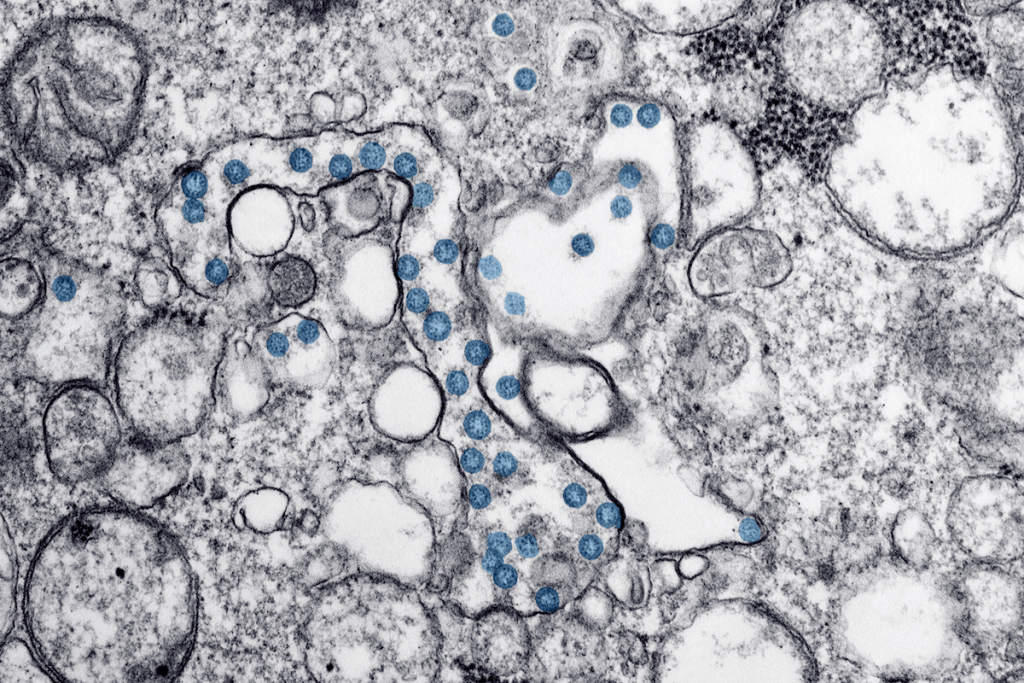

Transmission electron microscopic image of an isolate from the first U.S. case of COVID-19. The spherical viral particles, colorized blue, contain cross-sections through the viral genome, seen as black dots. CDC / Hannah A Bullock; Azaibi Tamin

The WVDL has also stepped up to produce the viral transport media that preserves patient samples for testing — a key bottleneck in many places. The lab runs exactly the same kinds of tests for diseases in animals and has long made similar test kits for partners around the state. A team of eight to 10 staff is now able to produce up to 10,000 kits a week.

The WVDL was able to make its first batches of test kits using materials on hand as soon as WSLH needed them and has shipped in fresh materials to keep producing media for as long as necessary. The lab also continues to fulfill its duties to animal testing.

“We already had a strong collaborative relationship with the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene,” says Keith Poulsen, director of the WVDL and professor at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine. “That relationship has made it easier to deal with difficult times like this.”

Although the global surge in demand for testing materials has made the test harder to conduct in many places, WSLH’s colleagues at the university have pitched in to keep testing available in Wisconsin.

UW Hospital and WSLH have also been working closely together. They’ve traded materials to allow both WSLH and UW Hospital’s clinical lab to continue testing patients. The WSLH has provided validation and educational materials to UW Health and to dozens of other health systems around the state to boost statewide testing capacity.

And WSLH has received support from within its own ranks. Other divisions within the agency have offered time, materials and expertise to assist with testing.

New rapid tests are starting to roll out, Sterkel says, and this could improve the ability of hospital labs to diagnose patient samples. The tests can provide health care workers and their patients with results in as little as five minutes. They’re also easy to use and are familiar to doctors and nurses, who have been using similar tests for infections like the flu for years. As these rapid tests come online, WSLH will incorporate them to help with quick diagnosis when time is of the essence.

The rapid tests might also relieve some pressure on the global demand for materials since they rely on a different supply chain than the current, more labor-intensive testing method. Yet, one item all the tests have in common is the nose-and-throat swabs used to collect samples from patients. The swabs remain in short supply.

WSLH’s colleagues across the university have stepped up to help by donating some of the necessary reagents, supplies and more.

The WSLH will continue to offer testing based on polymerase chain reaction detection. That’s because it remains a bedrock for responding to evolving infections. It is adaptable and can be quickly directed at new viruses.

“This allowed us to start testing (for the novel coronavirus) before anybody else in the state. It is also much cheaper than these rapid kits, allowing us to offer free testing. And it is easier to scale up than the rapid methods, meaning we can test many more people in a day,” says Sterkel.

For now, WSLH continues to test hundreds of samples a day, not only for COVID-19, but also for other infectious diseases that affect the health of the state’s residents. The lab remains grateful for the strength of its unique partnerships.

“It has been an amazing collaborative effort of people coming in to join together to meet the needs of the state,” says Sterkel.

Tags: animal research, health, state relations