Wisconsin corridor turns testbed for connected vehicle technology

Park Street at the intersection of University Avenue in the heart of the UW–Madison campus will become a connected vehicle corridor to test out new transportation technology. Photo: Jeff Miller

In an ambulance rushing a heart attack victim to the hospital, every second counts. If the ambulance and traffic signals could work together to clear traffic, the time saved could be a life-saver.

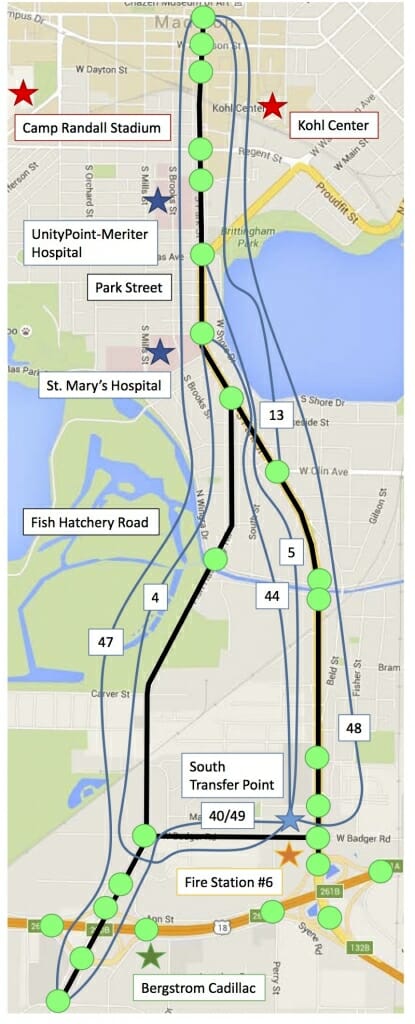

The eventual 6.2-mile corridor will connect the campus with the Beltline Highway. It serves emergency vehicles for two hospitals and a fire station and frequently handles heavy event and bus traffic. Image courtesy of Jon Riehl

The technology allowing transportation infrastructure and moving people and vehicles to “talk” to each other — switching signals to green just in time for an ambulance, or warning drivers of dangerous conditions as they develop — is a step on the path to a future that includes fully autonomous vehicles.

A team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Madison traffic engineers are establishing a testbed for that future on Park Street, the north end of an eventual 6.2-mile corridor linking the UW–Madison campus with Madison’s Beltline Highway.

In early 2018, researchers will install radio units on five traffic signals along the busy street and in at least four city-owned vehicles that frequently travel the area.

“This connected vehicle corridor is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation-designated Wisconsin Automated Vehicle (WiscAV) Proving Grounds,” says Jon Riehl, a researcher in the UW–Madison College of Engineering’s Traffic Operations and Safety (TOPS) Laboratory, which is leading the WiscAV effort. “Connected vehicles and autonomous vehicles are separate right now, but half of the nation’s 10 proving grounds are currently pursuing connected vehicle projects because all autonomous vehicles will eventually be connected, as well.”

The backbone of Madison’s corridor — already installed by city engineers in anticipation of future needs — is a high-speed, fiber-optic network connecting traffic signals and advanced traffic controllers.

Once the radio units, which were donated by private companies, are installed, city staff and UW–Madison engineers and computer scientists will test the technology and develop tools initially focused on safety. In parallel, UW–Madison engineers will simulate the corridor in a virtual reality environment.

“The city’s goals for this proof-of-concept project are to develop applications that demonstrate the value of connected vehicle technology to the public and will help us obtain federal grants to expand the corridor to more than 20 infrastructure units,” says Yang Tao, Madison’s assistant city traffic engineer. “We want to improve safety and mobility while also promoting equity.”

The new corridor presents plenty of research opportunities. It connects downtown Madison with the area’s only freeway, serves emergency vehicles frequenting two hospitals and a fire station, and often handles event traffic from UW–Madison’s sports stadiums.

Because the corridor includes a public transportation hub and heavy bus traffic, it also addresses the city’s mobility and equity goals. Tao ultimately hopes to install radio units on city buses to facilitate communication with connected traffic signals. When the bus unit detects a substantial delay from its schedule, a signal priority mechanism could help the bus catch up.

Peter Rafferty, a TOPS Laboratory program manager, says the connected vehicle corridor is a key addition to WiscAV.

“We are excited to partner with the city, since our ability to conduct real-world tests of connected vehicle systems will greatly benefit our research in the autonomous vehicle area,” he says.

Rafferty and David Noyce, UW–Madison professor of civil and environmental engineering and TOPS Laboratory director, serve on Gov. Scott Walker’s steering committee on connected and autonomous vehicle testing and deployment.

“Wisconsin is quickly becoming a national leader in connected and autonomous vehicle research,” Noyce says. “With a recently established collaboration with Southeast University in Nanjing, China, which houses that country’s top-ranked transportation engineering program, we’ll be able to lead this kind of research on an international scale.”

Tao also hopes to position Madison among the top-10 cities in the country for connected vehicle technology.

“This is one of many strategies we are pursuing to tackle Madison’s transportation challenges in the next decade or two,” he says. “Our collaboration with an academic

research powerhouse like UW–Madison is key to the project’s success because the public and private sectors need to work together to ensure that this new technology is developed to serve the interests of all members of our society.”