WARF, UW-Madison again rank in top 10 universities for U.S. patents

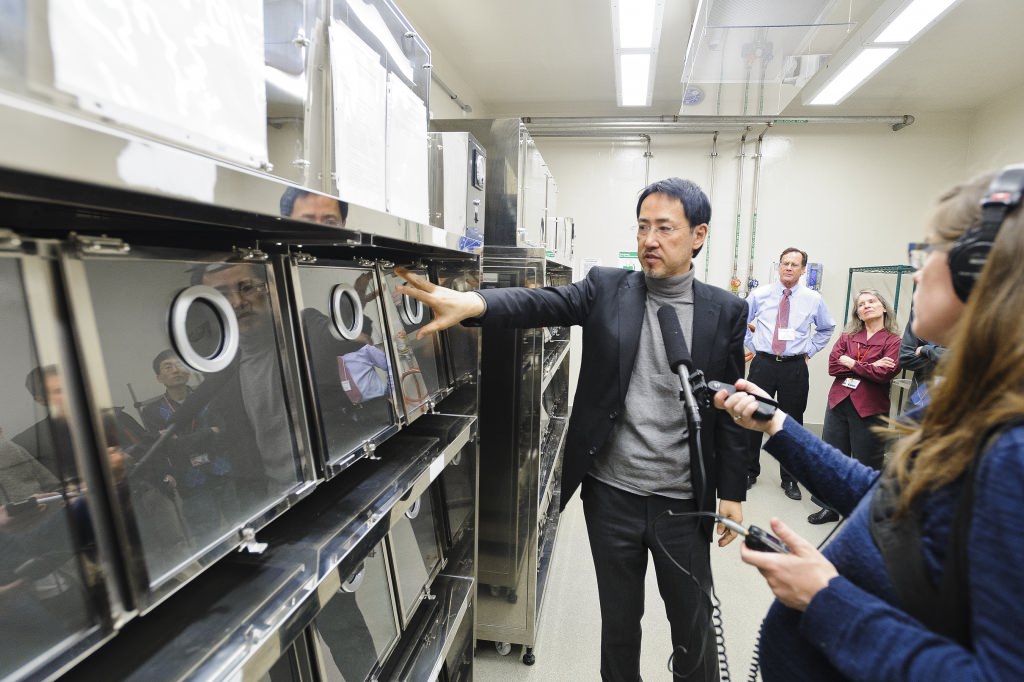

Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a professor of pathobiological sciences in the School of Veterinary Medicine, was awarded one of the 161 patents at the University of Wisconsin–Madison during 2015. In 2013, Kawaoka talked to the media during a tour of the Influenza Research Institute. Photo: Bryce Richter

An annual report issued last month ranks the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF), the private nonprofit foundation that manages intellectual property on behalf of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, as 7th among the world’s universities in U.S. patents issued in 2015.

The report, “Top 100 Worldwide Universities Granted U.S. Utility Patents,” by the National Academy of Inventors and the Intellectual Property Owners Association, credited WARF with 161 new patents.

“Utility patents” cover materials, processes, functions and devices. In contrast, “design patents” cover nonfunctional elements like appearance.

Pharmaceuticals and drug discovery, medical imaging, materials and chemicals, information technology and clean technology were the leading categories of WARF-UW-Madison patents.

The 161 patents places Wisconsin’s flagship university behind the front-running University of California System, MIT and Stanford, but ahead of the rest of the Big Ten, Harvard and Johns Hopkins.

“This is welcome news,” says Michael Falk, general counsel of WARF, “and it reflects the combination of an outstanding research university and a top-tier intellectual-property organization. WARF is one of the first technology transfer offices at a U.S. university, and we have developed a level of sophistication that is different than what’s found at other offices.”

Examples among the 161 patents include:

- A method for generating influenza vaccines that lack the genes needed for replication yet still elicit a strong immune response.

- A means to study tissue in the cervix with ultrasound to assess the likelihood of preterm birth.

- A system to improve the efficiency of heat-transfer fluids that solar plants use to concentrate the sun’s heat to drive electric generators.

In addition, Falk says, “WARF’s 2015 numbers of newly executed licensing agreements were up from the previous year. This demonstrates continued growth in the number of active licenses WARF manages.”

One reason why UW–Madison “punches above its weight” in terms of patentable inventions is the broad range of expertise on campus, Falk says. “So many inventions come from multiple departments, from investigators working in very different fields. One of the top five reasons that our inventors give for liking to work at UW–Madison is the ease of finding a collaborator on campus. They may have a biological background and need help thinking about a problem with big data sets. There is sure to be a collaborator on campus who is willing to talk, potentially collaborate and potentially invent together.”

“So many of the traditional core strengths of this university are now being exploited in new and exciting ways.”

Michael Falk

Another reason relates to the structure of WARF — based on what Falk calls the “really powerful vision of Harry Steenbock,” a UW–Madison biochemist and WARF founder who in 1923 invented a method to use ultraviolet radiation to produce vitamin D in milk, which eliminated the bone disease rickets in the United States. “Steenbock had the right and opportunity to become a millionaire,” Falk says, “but he chose instead to go through this arduous task of helping found WARF and dedicated his patent to the good of the university.”

Although both the inventor and the academic department are rewarded when WARF receives licensing money on its patents, that altruistic spirit still motivates scientists and inventors on campus, Falk says. With its portion of licensing income, WARF funds projects and personnel across the entire university.

Founded in 1925 as an independent, nonprofit foundation, WARF is UW–Madison’s designated technology transfer organization. WARF manages more than 1,700 patents and has provided $2.3 billion in cumulative grants (on an inflation-adjusted basis) to UW–Madison since its founding.

The strong patenting numbers are also rooted in a land grant university that combines traditional liberal arts and sciences with engineering, medicine and agriculture. “Madison is a powerhouse in the life sciences,” where historically significant departments like bacteriology now support entirely new endeavors, Falk says. “Who knew that in the 21st century this whole new industry, biotechnology, would develop and rely on bacteria as the starting point? So many of the traditional core strengths of this university are now being exploited in new and exciting ways.”