Vaccine opt-outs dropped — barely — when California added more hurdles

In response to spiking rates of parents opting their children out of vaccinations that are required to enroll in school — and just before a huge outbreak of measles at Disneyland in 2014 — California passed AB-2109. The law required that parents who wanted to exempt their children from vaccines get the signature of a healthcare provider who shared the risks of not being vaccinated, adding additional steps to opting out.

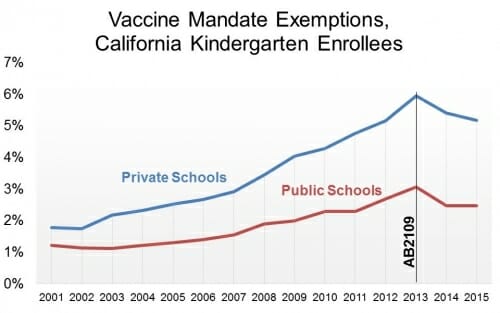

Percent of California kindergarteners with any kind of exemption for mandatory vaccines over 15 years. A stricter law made exemptions more difficult to get for the 2014 and 2015 school years, and exemption rates dropped. Image courtesy of Malia Jones

New research out of the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Applied Population Laboratory reveals that the law reduced the proportion of unvaccinated children entering kindergarten in California. But that reduction was modest, and, perhaps more significantly, the clustering of large numbers of under-vaccinated children in particular schools — the scenario most likely to spark outbreaks — barely budged.

Following the passage of AB-2109, the exemption rate dropped from its peak of 3.3 percent of kindergarteners to 2.7 percent in each of the following two years.

“That statewide rate is misleading, because it’s actually much worse than that,” says Malia Jones, the lead author of the new study and an assistant scientist in the Applied Population Laboratory, which is within the Department of Community and Environmental Sociology.

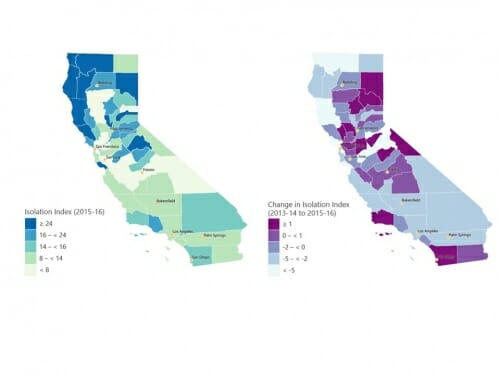

The county-level change in the clustering of exempted students following passage of a law making it more difficult to obtain an exemption from school-mandated vaccines in California.

Jones explains that the isolation index, the probability that an exempted student will encounter another exempted student in her school, dropped only slightly from 16 percent to 15 percent. The isolation index was 10 percent at the beginning of the study period, which goes back to the 2001-2002 school year.

“So we saw a dent in exemptions, but not really in clustering,” Jones says. The clustering of unvaccinated students together can more readily lead to outbreaks of preventable diseases.

The new study was published in the journal Health Affairs on Sept. 4, and Jones is presenting the results today, Sept. 17, at a briefing in Santa Monica. Jones collaborated with researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins University and Emory University to perform the analysis.

With years of public records on the vaccination status of incoming kindergarteners, California was a perfect location to study the effect of changing laws on vaccination rates. Researchers had access to data for the entire population, including information on both public and private schools, only excluding those kindergarten classes with fewer than 10 students enrolled.

And California has, like several other states, seen a precipitous rise in parents opting their children out of vaccines normally required to enroll in school, like those against measles and polio. That exemption used to require only the signature of a parent. But AB-2109 required that parents seeking an exemption for reasons other than religious belief meet with a physician, who counseled them on the benefits and risks of vaccination before signing a waiver.

“We wanted to know if that law worked,” says Jones.

And it did. The year after the law passed, the exemption rate dropped six-tenths of a percentage point, and held steady the next year. But that drop wasn’t the whole story. In addition to only minor changes to the clustering together of under-vaccinated children as revealed by the isolation index, Jones and her colleagues saw uneven changes in another category: conditional admissions.

Many students are enrolled conditionally when they meet some, but not all, of the vaccine requirements and are not claiming an exemption. Most likely, these children are simply behind on required vaccines and waiting until the appropriate time to get a booster shot. But there is little information about whether and how these children eventually meet all of the vaccination requirements.

Conditional admissions rose slightly the year following passage of AB-2109 before dropping 2 percentage points to 4.4 percent in the 2015-2016 school year, the study found. The vacillating numbers were hard to interpret, Jones says.

“We’re not sure those kids are really unvaccinated,” says Jones, who explains that few studies include this group of children, despite them being a large cohort. “But we think they’re less likely to be vaccinated.”

California wasn’t satisfied with AB-2109. In 2015, following the Disneyland measles outbreak, the state passed SB-277, which did away with all non-medical exemptions. Exemption rates have since gone down substantially. But Jones says the lessons of AB-2109 may be instructive for other states considering adding obstacles to receiving exemptions from mandatory vaccines — but not banning exemptions entirely.

“Making it a little bit harder to get an exemption is a much more feasible strategy for most states,” says Jones.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant 5R01AI125405-02).