UW scientists track Sandy’s fury

Hurricane Sandy has earned it reputation as a perfect storm, even among meteorologists.

But while Louis Uccellini, environmental prediction chief for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said, “This is the worst-case scenario,” the storm researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison weren’t so sure.

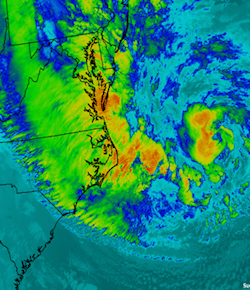

Satellite images like this one of the Eastern Seaboard helped scientists at UW–Madison predict the course of Hurricane Sandy with remarkable accuracy.

Courtesy of CIMSS

“The worst case would be a bad prediction,” said Chris Velden, senior researcher with the Madison-based Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS).

Without an accurate idea of when and where the storm system will dump rain, push ocean water and bend trees, emergency planning would be little more than guesswork.

“The models pegged this,” Velden said. “We know who is in the way of the storm and what should happen when it arrives.”

Parked in front of banks of monitors Monday on the second floor of the Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Science Building, Velden and about 20 scientists picked through storm plots and barometric pressure readings and water temperatures coming in from the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service — including data fed to those agencies from satellites through Madison and CIMSS.

“Have we ever had a prediction of this detail this far out?” asked Kyle Griffin, a graduate student in atmospheric sciences. “It wasn’t that long ago that the error range for these predictions was on the order of three days. In this case, there are models that are going to be off by maybe an hour.”

Predictions for Sandy’s Monday landfall were remarkably accurate. Three days ago, when Sandy was departing the Bahamas, 20 computer models showed the storm crossing onto land Monday afternoon in New Jersey.

“When the storms are out at sea, you look at them and say, ‘Wow, look at that beauty. But then it approaches the coast, you think about all the people there, and your heart sinks.”

Derrick Herndon

Two days before that, the models were eyeing half the Eastern Seaboard from the Carolinas to Canada. Two days before that, three of the models were thinking Sandy would head out east into the Atlantic.

“When this happens, we can use these tools with new confidence,” said Jonathan Martin, UW–Madison atmospheric sciences professor. “You say, ‘Wow, what else can I predict?’”

It also serves to improve the already sharp tools at the researchers’ disposal.

“We’ll look at which models got this right, and of the ones that get it right we’ll look at what is different about the physics on those models,” said Derrick Herndon, CIMSS senior researcher.

The contribution from UW–Madison, the birthplace of satellite meteorology, is key to that improvement.

“A lot of what we want to know about hurricanes takes place over oceans, where we could only get observations if a ship happens to be passing by,” Herndon said. “So we have to use satellites, and that’s what this center is all about — using satellite observations of the atmosphere to improve our understanding and predictions of the weather.”

That satellite focus on ocean storms means Madison researchers spend plenty of time watching some of nature’s most powerful forces work from thousands of miles away. The experience starts as an academic exercise — even as appreciation — but often takes a sobering turn.

“When the storms are out at sea, you look at them and say, ‘Wow, look at that beauty,’” Herdon said. “But then it approaches the coast, you think about all the people there, and your heart sinks. That motivates us to improve the science, make the models better and make sure they have the best warning we can provide.”