UW-Madison storage ring designated as historic site

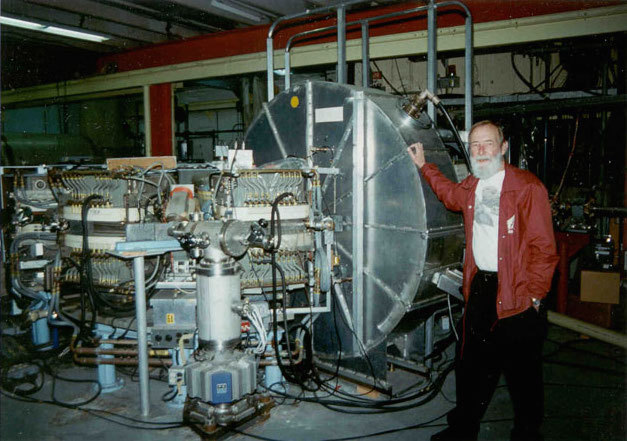

Ednor Rowe stands next to elements of the Tantalus storage ring, the world’s first dedicated source of synchrotron light. Rowe was the first director of the UW–Madison synchrotron radiation facility and the lead accelerator scientist for the Aladdin and Tantalus storage rings.

The world’s first dedicated source of synchrotron radiation, an electron storage ring named Tantalus, has been designated a historic site by the American Physical Society.

The designation recognizes the pioneering use of synchrotron light for scientific research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Synchrotron light, which extends from the X-ray to the infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, occurs when electrons, moving at near light speed, are forced to change direction through the influence of a powerful magnetic field.

In nature, synchrotron light is generated by charged particles speeding through space and influenced by powerful magnetic fields. The light can also be produced artificially in electron storage rings and is used to underpin a wide range of scientific applications, including studies of matter and advanced materials as well as uses in biology and medicine.

Tantalus, which was about the size of a backyard trampoline, was first used experimentally in 1968 and proved to be a scientific workhorse until 1987. In its nearly 20 years of operation, Tantalus was the basis for more than 2,000 scientific papers ranging from mapping the band structures of exotic materials to etching advanced computer chips using bright X-ray light.

In its nearly 20 years of operation, Tantalus was the basis for more than 2,000 scientific papers.

A once unique quality of the ring was its designation as a “user facility,” a resource that could be tapped by a community of researchers from a variety of institutions, notes Albrecht Karle, chair of the UW–Madison physics department.

In 1995, sections of the Tantalus ring were acquired by the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, where they still reside.

A great deal of the research done using Tantalus was accomplished by visiting scientists who traveled to Wisconsin from around the world to run their experiments on the device, which was located on the edge of a cornfield in rural Dane County near Stoughton, as well as on its much larger successor, Aladdin.

Especially active were researchers from a group of Midwestern universities, according to Dave Huber, an emeritus professor of physics and the former director of the UW–Madison Synchrotron Radiation Center.

“Many of the fundamental techniques for doing synchrotron radiation studies of solid state materials were worked out on Tantalus,” Huber notes. “A lot of people came from other countries, went home and were influential in setting up their own synchrotron facilities.”

The historic site designation was presented by American Physical Society President Sam Aronson Friday (Nov. 13, 2015) to UW–Madison Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education Marsha Mailick.

Tags: institutional awards, physics, research