‘The Girl in the Picture’ and photographer of iconic Vietnam War image to speak at UW–Madison

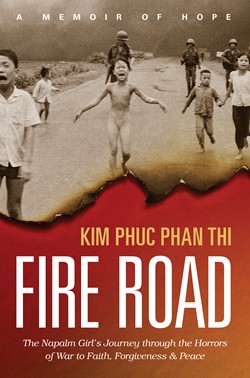

You’ve likely seen the horrifying picture of a naked little girl running after a napalm bombing during the Vietnam War. That little girl has grown up.

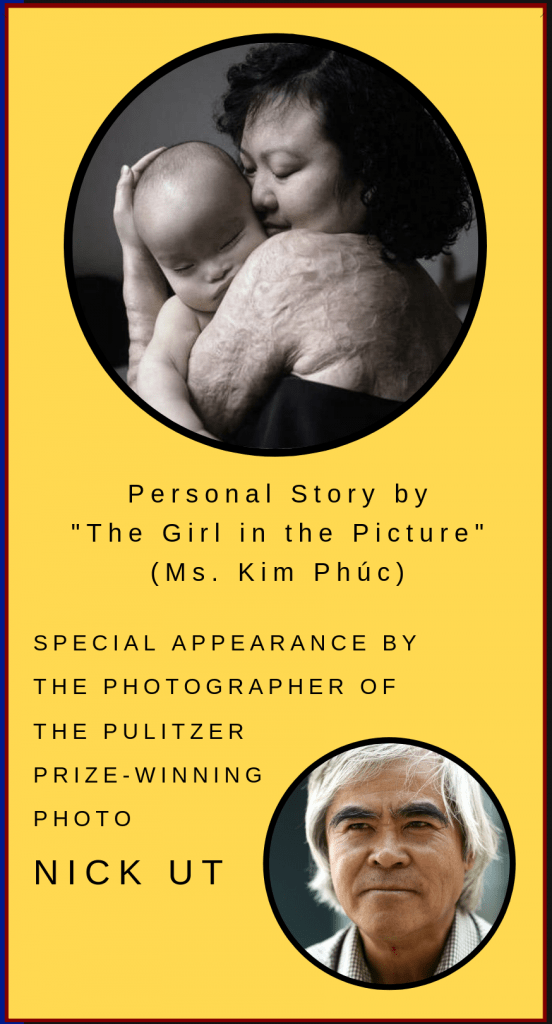

Kim Phúc, now 56, was known to the world as “Napalm Girl.” Now, she’s an author and an activist, winning the Dresden Peace Prize in February 2019. She will share her story at 5:30 p.m. June 8 in the Alumni Lounge of the Pyle Center, a co-sponsor of the event. “Celebration of Peace and Mindfulness” is a free event that includes a special appearance by Nick Ut, the photographer of the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo. Tickets are not required.

The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) is sponsoring the talk, which takes place 47 years to the day after the photo was taken.

“You can feel the impact of the bomb, you can see it,” says Mary E. McCoy, faculty associate in the Department of Communication Arts and CSEAS. “This photo connected human suffering to the air war. Suddenly, it wasn’t an abstract concept.”

Still, she has hesitated to show it in classes. She’s not alone.

“People have been reluctant because it seemed voyeuristic — that it was somehow a violation of her,” McCoy says.

Her view has changed after reading Phúc’s 2017 book “Fire Road: The Napalm Girl’s Journey through the Horrors of War to Faith, Forgiveness and Peace.”

“The fly-by was not an inconsequential event, for falling from that underbelly were four large ice-black bombs,” Phúc writes. “And as the bombs softly made their way to the ground, landing one by one, somersaulting end over end — whump-whump, whump-whump, whump-whump, whump-whump — I knew I had to flee. These were not bombs that fell heavily from the sky, as I had heard that bombs would do; no, these bombs all but floated down. There was something sinister in those cans.”

She was left for dead in a morgue with burns covering her body. As she eventually recovered, she dealt with anger and embarrassment from knowing the world had seen her at her most vulnerable. It took a long, long time but Phúc has accepted being known as the “Napalm Girl” and has used it as an opportunity to encourage peace.

“Forgiveness made me free from hatred,” Phúc told NPR. “I still have many scars on my body and severe pain most days but my heart is cleansed. Napalm is very powerful, but faith, forgiveness, and love are much more powerful. We would not have war at all if everyone could learn how to live with true love, hope, and forgiveness. If that little girl in the picture can do it, ask yourself: Can you?”

The Children’s Library International is funding the visit as part of an effort to raise funds for a library it is constructing in Phúc’s name in her home province of Trảng Bàng.

Mike Cullinane, associate director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies and a faculty associate in the Department of History, was already an anti-war activist before ever seeing the photo.

“It wasn’t a turning a point for me. I was already against the war. Napalm was already an enemy of everything I thought about,” Cullinane says. “This was just a confirmation photograph for me of something that should be eliminated.”

But the photo had power in showing others what was happening in a way that words couldn’t.

“You’re not dropping napalm on north Vietnamese soldiers. You’re dropping it on innocent noncombatant people,” Cullinane says. “This is a little girl. She just got napalmed. Why did that happen?”

In May, CSEAS held “The Terrors of War, Iconic Images in Teaching,” a professional development workshop for 21 Wisconsin K–12 teachers. The photo, and many others, were part of a discussion about the challenges teachers face when teaching history.

McCoy thought the workshop would show teachers how to teach the history of these events. She’s been surprised to see the other ideas teachers are sharing, including samples of future lesson plans that use the photo.

“They’re trying to get kids to think about how these photos could connect with them, which is not what I expected,” McCoy says. “I like the way these teachers are doing it better. They’re giving the kids agency and they’ll remember the photos in a deeper way.”

The teachers who were at the workshop will get to meet Phúc and Ut at a special luncheon the day of the talk. They won’t just talk about a 9-year-old girl. They’ll talk about the woman she grew up to be.

“The significance for me as a teacher is that this book and her visit make it not just OK but valuable to teach this photograph. I’m OK with it now because she’s OK with it,” McCoy says. “I told my class this last spring, finally I can teach this.”