Stressed parents rely on junk food for kids

Stressed-out people make bad food decisions, eating higher-calorie foods and eating more often. Stressed-out parents may be making those unhealthy choices for the children who depend on their judgment, new research finds.

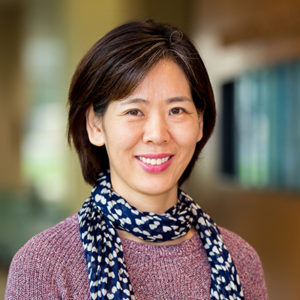

“Stress makes us choose more energy-dense foods, more comfort food,” says University of Wisconsin–Madison nursing professor Myoungock Jang. “When young kids are exposed to this kind of food environment, that influences the eating patterns they are learning.”

Jang and nursing professors Debra Brandon of Duke University and Allison Vorderstrasse of New York University surveyed parents from 256 U.S. families with children ages 2 to 5. The researchers assessed the parents’ psychological well-being, sleep quality, and family mealtime habits and food choices.

“The higher their psychological distress, the less healthy food is available in the home and the more unhealthy the feeding practices are for their children,” says Jang, whose findings were published recently in the journal Nursing Research.

In-depth interviews with some of the parents showed that stressed families were prioritizing convenience.

“More often they didn’t feel they had enough energy and time to prepare food at home,” says Jang. “So, they were making choices like eating fast food more, and bringing home processed food that doesn’t take much work to prepare — but also isn’t healthy food.”

It’s a temptation that Jang, parent to a six-year-old, knows all too well.

“Sometimes I just don’t feel like I can battle with my son at the dinner table — ‘You need to eat more of this, more of that,’ ” she says. “So, we make something or go somewhere where I know I won’t have to entertain him, and I can kind of take a break.”

The researchers expected the reliance on less-healthy eating would result in higher rates of obesity among the children of parents experiencing more psychological distress. But while stressed adults did choose more unhealthy meals for their families, the study found no connection between parental stress levels and their child’s body mass index.

“The kids in the study were so young, and there isn’t as much obesity among those ages,” says Jang. “But we know that their eating patterns are established during this time in their life, and we wonder if this will influence their health when they begin to slow down and are more likely to gain weight.”

Jang would like to track that development in future studies, and watch for the influence of support from other parents.

Acknowledging the importance of developing healthy eating habits and the way stress can derail those efforts is a first step for parents trying to make sure they have healthy food on hand, time to prepare it and a relaxed environment to eat in, according to Jang.

“All parents are stressed to some level. We can’t avoid it,” she says. “So, it’s good to recognize that it’s important to try to do this the right way even though you’re stressed.”

One way to ease the burden might be to share the effort with friends.

“Some parents make a good strategy of preparing for the week in advance. But that’s not easy for everyone, all the time,” Jang says. “That is where peer support, parent-to-parent, would be great. Sharing information, sharing child care resources and emotional support, that may be a way to help stressed parents avoid unhealthy feeding practices.”