‘Stories from the Flood’ recount suffering, resilience in Kickapoo Valley towns

It’s raining so hard it’s like you’re on a boat in a raging river. It’s like God is shuffling cards with our roof shingles. I felt at any moment my roof was going to blow off. It’s a very odd feeling because I hear rushing water not only up above but down below.

Abigaile Gricius, Chaseburg, from “Stories from the Flood, a Reflection of Resilience”

LA FARGE, Wis. – A standing-room-only crowd of area residents and government officials gathered Thursday, Nov. 7, to celebrate a story-gathering project focused on the floods of August and September of 2018.

Sparked by the epic 15-inch rainfall in late August, the Kickapoo River set flood-stage records up and down its valley in Southwest Wisconsin.

To date, “Stories from the Flood” has gathered over 70 written, audio, and video interviews with people who experienced what some call a “thousand-year flood” along the Kickapoo River and nearby Coon Creek.

The “Stories” project is a collaboration between the Driftless Writing Center and an undergraduate English seminar at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Both watersheds have endured seven devastating floods since 2007, and as residents search for answers, their recorded local knowledge of the events is a key source of both information and inspiration.

This musical little creek had turned into a vicious river that would spread out up to a half mile wide.

David Miller, Ontario, from “Stories from the Flood, a Reflection of Resilience”

Although 2018 produced the highest water in memory, flooding and erosion are common in the area. To stem disastrous soil erosion in the 1930s, the Coon Valley watershed became the first demonstration project for the federal agency now called the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

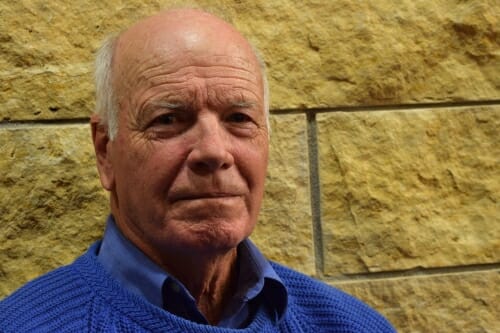

The Gays Mills Community Center was a gathering place for meals and supply donations for hundreds of people after the flood. “You speak of resilience,” resident Craig Anderson said in La Farge last Thursday. After the floods of 2007 and 2008, “We were fed from the Red Cross disaster trucks… . Last year, we did not need those trucks. We cared for ourselves in the community center we built after the 2008 flood.” Photo by Tim Hundt

“Stories from the Flood” was conceived soon after the floodwaters subsided, said project director Tamara Dean, a board member at the Driftless Writing Center, which oversees the project. Getting people to take part “wasn’t a slam dunk, it wasn’t easy at first,” says Dean, referring to the modesty that is typical of the region. “People, even if they lost everything, said, ‘Others had it worse than me. Talk to them.’”

The Wisconsin Humanities Council started funding the project in February, and interviews began in April. Volunteers from the Driftless Writing Center held workshops at libraries throughout the watershed, then began interviewing survivors individually. This fall, undergraduates in an English seminar at UW–Madison have been conducting interviews.

I’m so thankful for our friends. Because we needed a lot of help.

Jean Steiner, La Farge, from “Stories from the Flood, a Reflection of Resilience”

UW-Madison undergraduate Marissa Beaty, speaking to the La Farge meeting: “This was a really shocking experience… but every story we heard, has largely been positive, no matter how much you lost. I will continue with this project, I’ve become so invested, cared so much about this, it’s honestly been a life-changer for me. I thank you for allowing us to be part of this.” Photo by David Tenenbaum

“The student engagement blew my mind,” says Caroline Gottschalk Druschke, an associate professor of English, who received a Morgridge Center for Public Service course development grant to focus the community-based learning seminar on Stories from the Flood this semester. “I do a lot of field science and am working on a second masters at the Center for Limnology … so it’s wonderful to see how a true humanities-based project had so much power for demonstrating what happened here. It’s incredible to see the connective tissue” linking ecology, the social sciences and policy in the Kickapoo and Coon Creek valleys with the humanities.

“We have been collecting stories, mostly one-on-one, but had not brought the storytellers together,” Dean said. “I was surprised by how open people were in the group, we don’t see that all the time around here.”

The audience in La Farge included people who endured the flood, those who helped record stories from August, 2018, and local government officials. Photo by David Tenenbaum

Volunteers from the Driftless Writing Center and its partners aim to collect at least 200 stories. Transcripts from the narratives will be coded and indexed, with help from students at UW–Madison. This will allow future researchers to understand themes from the conversations, and serve as a basis for a report for public officials. Though interviews continue, the evening served as a kind of culmination for the project.

Paul Hayes, of Westby, awoke three times during the August, 2018, storm, listening to the roar of water produced by two dam breaks upstream. “It came right in the back door of the pole shed, and out the front door – our house was high and dry … but the emotional impact … I have become addicted to checking radar in the middle of the night when it’s raining. We are not always afraid, but we are locked into it. The roaring, the cataract, still haunts me like a demon.” Photo by David Tenenbaum

Suitably, the event was held at the Kickapoo Valley Reserve, an 8,589-acre ecological reserve built on land that the federal government bought for a dam on the Kickapoo River. The dam faced so much ecological and economic opposition that it was never completed. The reserve represents an effort to live with nature by pulling back from riverbanks, reducing threats to people and their buildings, and giving water room to percolate into the soil.

Not coincidentally, all these subjects arose during the evening session in La Farge. But what seemed strongest was a mixture of resignation and resilience, and trepidation about community survival.

“People are leaving, and that’s devastating to your sense of home,” says Kile Martz, who is still doing recovery work on residential properties he owns in Gays Mills more than 14 months later. “A lot of people you know, have interacted with on a daily basis, are not in your life anymore, because they wanted get away from the next disaster. It’s very detrimental to the community.”