Standing CT for horses, developed at UW-Madison, fills longstanding need in veterinary medicine

At California’s Santa Anita Park, in a single season, nearly 30 horses lost their lives during racing or training, some due to injury. This prompted the temporary closure of the prominent horse racing course in the summer of 2019.

This and other instances of catastrophic injuries in racehorses have recently drawn critical attention to the sport. As the industry searches for solutions, scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have created a diagnostic imaging tool that could help prevent these injuries through early detection and monitoring: a standing helical computed tomography (CT) scanner named Equina.

It is the first CT scanner on the market to vertically scan the lower legs of a standing, sedated horse and also the first dual-purpose standing CT machine. This means it can scan up and down a patient’s legs and move horizontally to scan the head and neck – three areas of the body where CT is advantageous in teasing out anatomical intricacies.

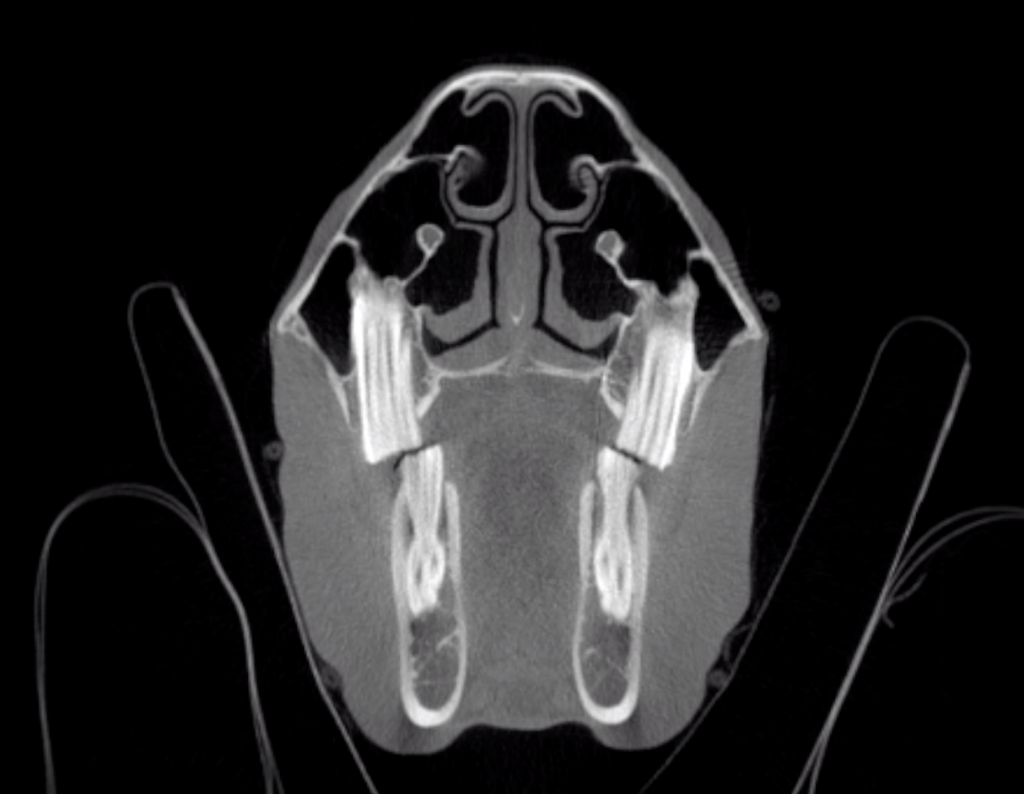

The system fills a longstanding, unmet need in the diagnosis and treatment of a variety of conditions facing horses and other large animals. Already, more than 150 horses ranging in size from a miniature horse to a draft horse have been scanned at UW Veterinary Care, the teaching hospital of the UW–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM), using the new system. This has led to findings undetectable by earlier methods, including a brain tumor, an orbital tumor behind the eye, and diseases of the feet, teeth and sinuses.

“The CT has changed the way we can evaluate lameness and orthopedic injury in the distal limb and has virtually replaced radiography (X-rays) as the gold standard diagnostic for disease of the teeth and skull,” says Samantha Morello, clinical associate professor of large animal surgery at the SVM.

The first Equina machine was installed for evaluation in the winter of 2018 at UW Veterinary Care and the service is now available for patients of its Morrie Waud Large Animal Hospital. It is currently the only machine available in Wisconsin.

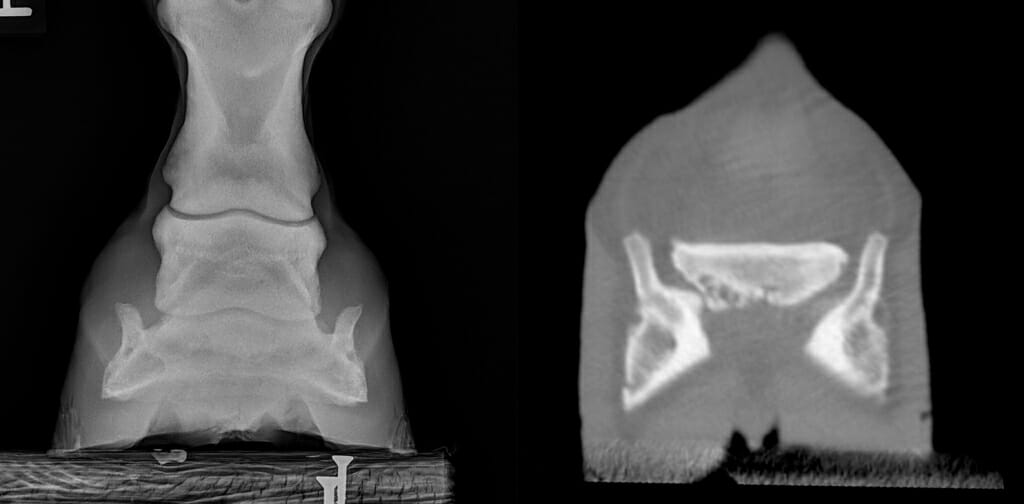

Standing CT holds several advantages over other diagnostic tools currently available for horses. For one, CT images provide improved imaging of bone and soft tissue compared to traditional X-rays, aiding diagnosis and treatment plans.

The technology, says the SVM’s J.R. Lund, a clinical instructor in diagnostic imaging, also allows for easier and faster imaging, and improves the ability of clinicians to discern what’s happening with their patients.

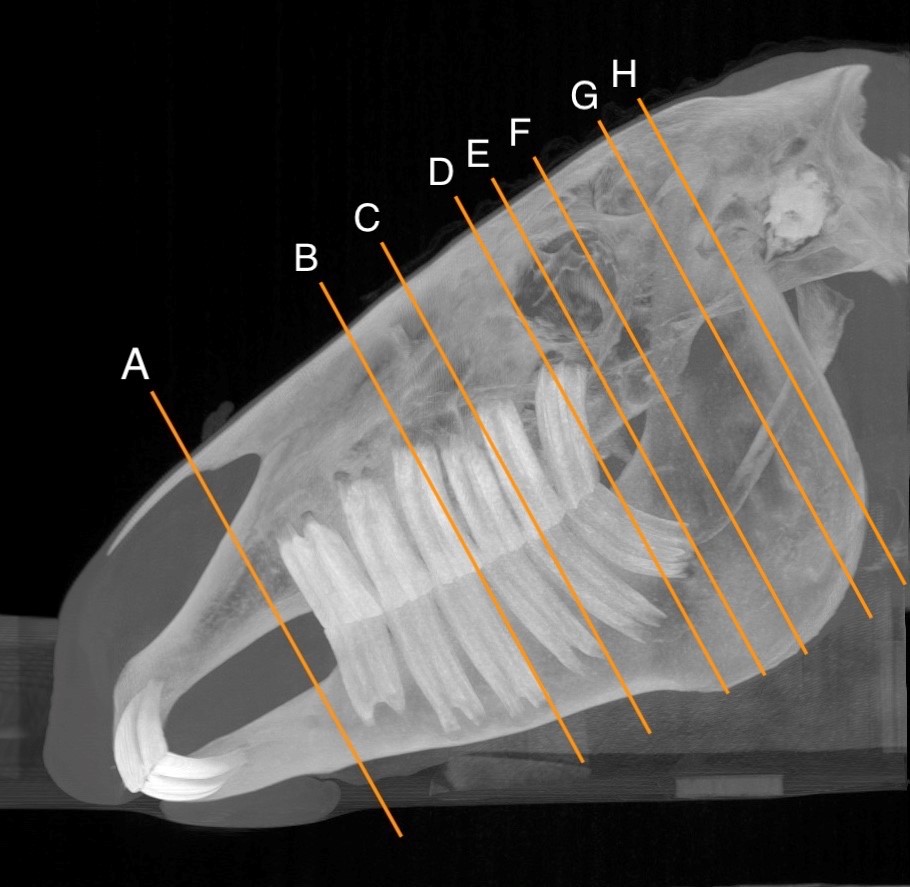

While X-rays yield a two-dimensional version of a three-dimensional object, which can lead to obscurities, CT “removes that layer of ambiguity” through three-dimensional, cross-sectional images, explains Ken Waller, clinical associate professor and section head for diagnostic imaging.

“To use a loaf of bread analogy, I can slice the loaf, take out a slice and look at it,” Waller says. “Then I can put that slice back, slice the bread in different directions, and take those slices out individually.”

A comparison of radiograph (X-ray), left, and computed tomography (CT), right, imaging of portions of the coffin bone (on the sides) and navicular bone (centrally located) of a horse. Multiple dark regions within the left side of the navicular bone indicate degenerative change consistent with navicular syndrome. CT is much more sensitive to these changes than radiographs and allows clinicians to evaluate the navicular bone in a three-dimensional manner without superimposition. CT also allows for improved evaluation of the soft tissue structures, such as tendons and ligaments. UW School of Veterinary Medicine

In addition, because a horse can remain standing in the scanner and only requires sedation, there’s no need for general anesthesia – a cost savings for the client and safety advantage for the patient and hospital personnel. Anesthetizing a large patient like a horse is resource-intensive and carries a risk of complications and stress-related injuries, a limitation of conventional CT machines that require the patient to lie recumbent on a table. Clinicians rarely pursue recumbent CT for horses and other large animals unless they are already planning to anesthetize the animals for surgery.

The ability to image horses and other large animals without resorting to general anesthesia makes CT technology available to “almost every patient and client that walks through our door, since it’s safe, fast and cost-effective,” says Morello.

The technology has also proven beneficial for students and veterinarians pursuing training at the SVM, and for referring veterinarians in the region, Waller says.

“We’re giving veterinarians a technology that they never had access to,” says David Ergun, an adjunct professor of medical physics at UW–Madison and CEO of Asto CT LLC, the company founded at the university that developed the Equina imaging system.

The idea for the machine began with Peter Muir, an orthopedic surgeon at the SVM who for more than two decades has studied bone biology and the mechanism that leads to stress fractures in racing greyhounds and thoroughbreds. As he learned more about condylar fractures, a stress fracture common in racehorses, and the challenge of detecting these fractures with radiographs, he realized that having new technology to screen for the injuries would be an important innovation.

The types of career-ending fractures suffered by racehorses and other performance horses often begin as small cracks or stress lesions in the bones of the lower leg, which then intensify under the impact of racing or other equine sports. These early signs of fracture are hard to detect on radiographs, but can be easily seen on CT.

In 2013, Muir approached Rock Mackie, then director of medical engineering at the Morgridge Institute for Research, with the idea of developing a vertical CT scanner for horses. Mackie, a UW–Madison professor emeritus of medical physics, has shepherded to development numerous medical technologies. He had previously worked with the SVM as co-founder of TomoTherapy, a radiation-based cancer treatment machine that was successful in early clinical trials in pet dogs with cancer. TomoTherapy ultimately found widespread use in human medicine.

As Mackie brainstormed with his team, Muir and others from the SVM worked up early prototypes. The end result “is sort of CT in reverse” says Muir. Cutting-edge robotics precisely move a 2,000-pound CT scanner around the horse. The intellectual property behind the technology was patented by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

The rugged, armor-plated machine is built by a partner company, Photo Diagnostic Systems, Inc., and is based on a large baggage scanner, with a number of refinements to accommodate horses rather than luggage and to withstand the rigors of veterinary practice.

“In a human baggage scanner, nobody is going to pee on it,” Mackie says with a laugh.

The system continues to be refined based on clinician feedback. Units have also been installed at the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine and will soon be at the University of Melbourne’s U-Vet Werribee Equine Centre in Victoria, Australia.

Equina’s creators hope that as the technology becomes more widely adopted, horses exhibiting lameness or other signs of injury can be screened for early signs of a break and treated before the fracture becomes a serious clinical problem.

“Because we can see a fracture on CT that we may not have been able to see with plain radiographs, we can make the decision to treat it much more aggressively and really minimize what the horse is doing so he doesn’t displace the fracture and have a catastrophic breakdown,” says Lund.

Muir and others at the SVM are pursuing multiple areas of clinical research around standing CT to advance equine studies. Asto CT is also exploring potential applications for the machine in human medicine, for example, in radiotherapy.

“We’re at the cutting edge of clinical knowledge. As this type of scanning technology is more widely adopted, it will drive innovation in clinical treatment of horses because more is being learned and new diagnoses are being made,” Muir says. “There are a lot of new chapters to this story and we’ve certainly got more we’d like to do.”